The announcement was presented — in official news reports, on social media — as a major victory for Chinese women. The government was set to overhaul its law governing women’s rights for the first time in decades, to refine the definition of sexual harassment, affirm prohibitions on workplace discrimination and ban forms of emotional abuse.

For many women in China, the response was: Hm, really?

The proposed revisions are the latest in a series of conflicting messages by the Chinese government about the country’s growing feminist movement. On paper, the changes, which China’s legislature reviewed for the first time last month, would seem to be a triumph for activists who have long worked to push gender equality into the Chinese mainstream. The Women’s Rights and Interests Protection Law has been substantially revised only once, in 2005, since it was enacted nearly three decades ago.

The government has also recently emphasized its dedication to women’s employment rights, especially as it urges women to have more children amid a looming demographic crisis. The official newspaper of China’s Supreme Court explicitly tied the new three-child policy to the revision, which would codify prohibitions on employers asking women about their marital status or plans to have children.

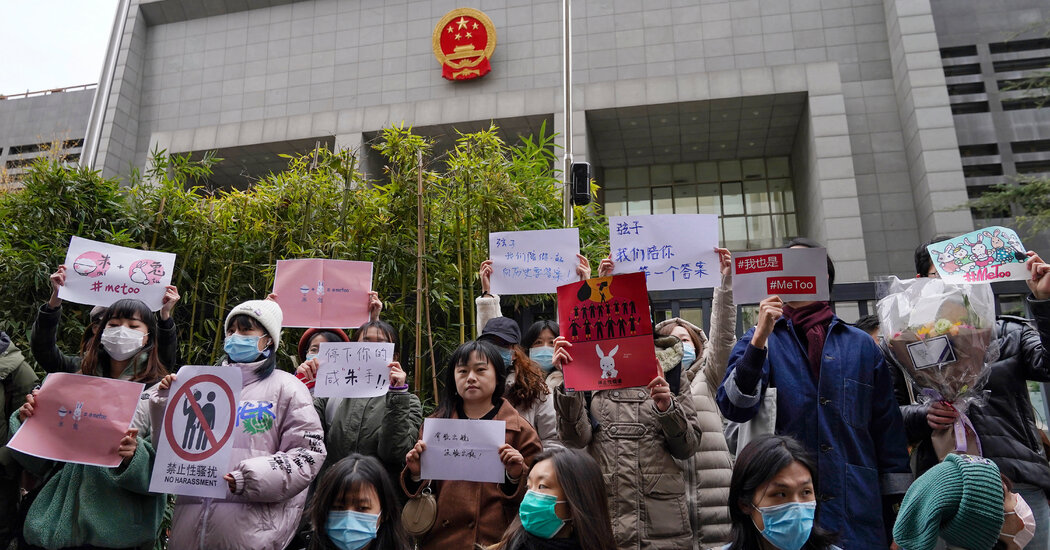

At the same time, the authorities, ever leery of grass-roots organizing, have detained outspoken feminist activists and sought to control the country’s fledgling #MeToo movement. Sexual harassment lawsuits — already rare — have been dismissed. Women have been fired or fined for lodging accusations. When Peng Shuai, a star tennis player, recently said on social media that a top Chinese leader had pressured her into sex, she was censored within minutes, and many worry that she is under surveillance.

Women have also been increasingly pushed out of the workplace and into traditional gender roles since China’s leader, Xi Jinping, assumed power. Some fear that the campaign to encourage childbirth could turn coercive.

The contradictions were clear in a recent article in the Global Times, a Communist Party-owned tabloid, about Chinese feminist advocacy. While the article hailed the proposed legal revisions as a “landmark move,” it also denounced “spooky ‘feminism’” and derided the “so-called MeToo movement” as yet another Western cudgel against China.

Feminist activists have warned against giving the revisions too much weight.

Feng Yuan, the founder of Equality, a Beijing-based advocacy group, welcomed the move for its potential to impose “moral responsibility and pressure” on institutions. But she noted that the draft does not specify clear punishments for the violations it outlines. Instead, it uses phrases such as “will be ordered to make corrections” or “may be criticized and educated.”

“This law, to be honest, is more of a gesture than a specific plan of operation,” Ms. Feng said.

The gesture, at least, is extensive. As revised, the law would offer the most comprehensive legal definition yet of sexual harassment, to include behaviors such as sending unwanted sexually explicit images or pressuring someone into a relationship in exchange for benefits. It also instructs schools and employers to introduce anti-harassment training and channels for complaints.

The law would also codify women’s right to ask for compensation for housework during divorce proceedings — following the first-of-its-kind decision by a Chinese divorce court last year to award a woman more than $7,700 for her labor during her marriage.

Some provisions would go beyond those in other countries. In particular, the draft bans the use of “superstition” or other “emotional control” against women. While the draft does not offer further details, state media reports have said those bans would cover pickup artistry. Pickup artistry — a practice that arrived in China from the United States — commonly refers to the use of manipulative techniques, including gaslighting, to demean women and lure them into having sex. It became a booming industry in China, with thousands of companies and websites promising to teach techniques, and it has been widely condemned by both the government and social media users.

Elsewhere, bans on emotional coercion are spotty. Britain banned it in 2015, while the United States has no federal law against it.

Yet the truly novel aspects of the Chinese law are limited. Many of the provisions already exist in other laws or regulations but have been poorly enforced. China’s labor law bans discrimination based on sex. The compensation-for-housework measure was included in a new civil code that went into effect last year.

While the law affirms women’s right to sue, its emphasis is largely on authorizing government officials to take top-down action against offenders, said Darius Longarino, a researcher at Yale Law School who studies China.

“The priority should be on bottom-up enforcement, where you empower individuals who have been harassed to use the law to protect their rights,” he said.

It is rare for victims of harassment to go to court. An analysis by Mr. Longarino and others found that 93 percent of sexual harassment cases decided in China between 2018 and 2020 were brought not by the alleged victim but by the alleged harasser, claiming defamation or wrongful termination. Women who have made public harassment claims have been forced to pay those they accused.

Nonlegal complaints can bring heavy consequences, too. In December, Alibaba, the e-commerce giant, fired a woman who had accused a superior of raping her. The company said that she had “spread falsehoods,” even though it had earlier fired the man she accused.

Even when women do sue their harassers, they face steep hurdles. Perhaps the most high-profile #MeToo case to go to court was brought by Zhou Xiaoxuan, a former intern at China’s state broadcaster, who asserted that Zhu Jun, a star anchor, had forcibly kissed and groped her. But the case faced years of delays. In September, a court dismissed the claim and said she had not provided enough evidence, though Ms. Zhou said the judges had rejected her efforts to introduce more.

In an interview, Ms. Zhou expressed skepticism that the revised law would change much.

“The judicial environment won’t be changed by one or two legal amendments,” she said. “It will take every court, every judge really understanding the plight of those who suffer from sexual harassment. This is probably still a very long, hard road.”

Emotional control could prove even harder to substantiate, especially in a country where open discussion of mental health can still carry a stigma. Guo Jing, a feminist activist from Wuhan, noted that psychologists are rarely admitted as expert witnesses in Chinese courts, and that judges might be skeptical of claims of depression or other mental health conditions.

And patriarchal attitudes still remain deeply entrenched. After the draft revisions were published, several male bloggers with large followings on the social media platform Weibo denounced the provisions against degrading or harassing women online, saying they would give “radical” feminists too much power to silence their critics.

Still, some women remain optimistic about the possible power of the proposed changes.

A woman in southern Guangdong Province who asked only to use her last name, Han, out of fears for her safety, said that she had endured years of physical and emotional abuse by her ex-husband. Even though she managed to secure a divorce last year, he continues to stalk and threaten her, she said. She obtained a restraining order, viewed by The New York Times, that cited chat logs and recordings.

Yet even with the restraining order, when Ms. Han called the police, they often told her that threats alone were not enough for them to take action, as he had not physically harmed her, she said. If the law were revised, she continued, the police would be forced to recognize that she had a right to seek their help.

“If the law changes, I will be even more convinced that everything I’m doing right now is right,” she said.

Joy Dong contributed research.