A cluster of severe hepatitis cases in Alabama children prompted the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention to issue a nationwide health alert on Thursday, urging doctors and health officials to keep an eye out for, and report, any similar cases.

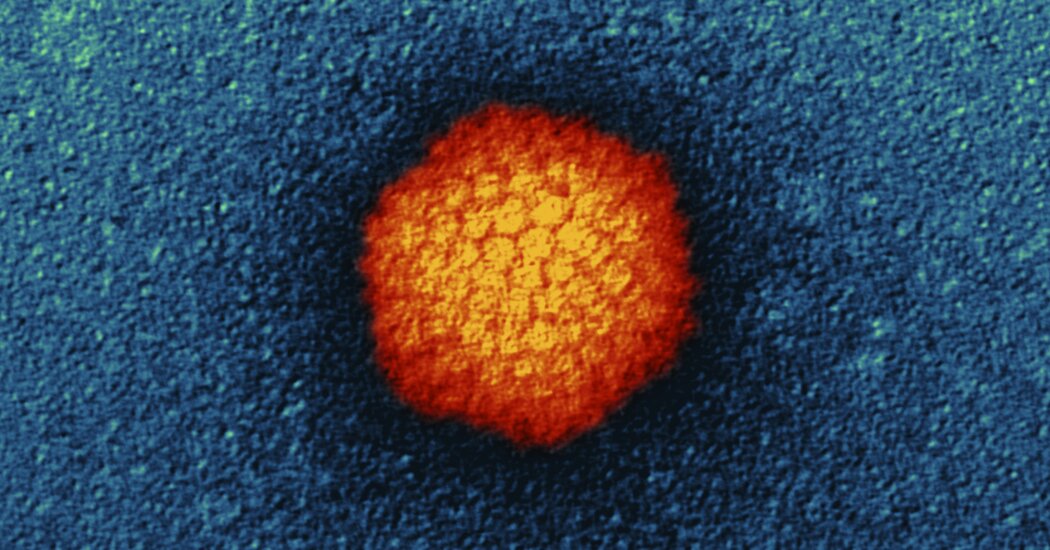

Officials are investigating the possibility that an adenovirus, one of a group of common viruses that can cause cold-like symptoms, as well as gastroenteritis, pink eye and other ailments, may be responsible.

Hepatitis is an inflammation of the liver that has a wide range of causes. Viral infections, especially those caused by the hepatitis A, B and C viruses, may lead to the condition. Heavy drinking, certain toxic chemicals, some medications and other medical conditions can also cause hepatitis.

The Alabama Department of Public Health has recorded nine unexplained cases of hepatitis in otherwise healthy children under the age of 10 that occurred between last October and February. None of the children died, but several developed liver failure and two required liver transplants.

All nine children tested positive for adenovirus infections. Several were determined to have what is known as adenovirus type 41, which typically causes diarrhea, vomiting and respiratory symptoms.

North Carolina has also identified two similar cases of severe hepatitis in school-aged children, both of whom have now recovered. “No cause has been found and no common exposures were identified,” Bailey Pennington, a spokesperson for the state’s Department of Health and Human Services, said in an email.

Adenoviruses have been known to cause hepatitis, though typically in immunocompromised children.

“It’s not typical for it to cause full-on liver failure in healthy kids,” said Dr. Aaron Milstone, a pediatric infectious diseases specialist at Johns Hopkins Children’s Center.

The C.D.C. has ruled out some common causes of liver inflammation, including the hepatitis A, B and C viruses, in the Alabama cases, the agency said in a statement on Thursday.

“At this time, we believe adenovirus may be the cause for these reported cases, but investigators are still learning more — including ruling out other possible causes and identifying other possible contributing factors,” the agency said.

Britain has identified more than 100 cases in children 10 and under since January; eight have received liver transplants. Of those cases that have been tested for adenovirus infections, more than 75 percent have been positive, according to the U.K. Health Security Agency.

“Information gathered through our investigations increasingly suggests that this is linked to adenovirus infection,” Dr. Meera Chand, director of clinical and emerging infections at the agency, said in a statement.

Israel’s Ministry of Health said on Twitter this week that it was investigating 12 potential cases.

Many questions remain about the hepatitis cases, which remain rare, experts stressed.

“It’s important not to panic,” said Dr. Richard Malley, an infectious disease doctor at Boston Children’s Hospital. “But I think, for all the reasons you can imagine, it’s important for the C.D.C. to ask clinicians across the country to be vigilant.”

Bertha Hidalgo, an epidemiologist at the University of Alabama at Birmingham School of Public Health, agreed: “A cluster of cases, especially among this age group, is definitely something to monitor closely.”

Although it is possible that an adenovirus is a cause, the connection remains unproven. Doctors noted that adenovirus infections are common in children, and that the children may have been infected with the virus incidentally.

So far, there is no clear connection to the coronavirus that causes Covid-19, experts said. Although several of the British children tested positive for the coronavirus, none of the Alabama children had Covid, according to the C.D.C.

Dr. Milstone said that he thought a connection to the coronavirus was “unlikely” but could not be entirely ruled out. “You have to put a question mark there,” he said.

The agency is asking health care providers to test children with unexplained hepatitis for adenovirus infections and to report those cases to health officials.

Signs of serious hepatitis include prolonged fever, severe abdominal pain and jaundice, a yellowing of the skin and eyes; caregivers who observe those symptoms should immediately contact the child’s pediatrician, Dr. Malley said. Even serious cases of hepatitis are treatable, he added.

And if the cases do have a viral cause, the same strategies that many families have used to reduce the risk of Covid — including handwashing and covering coughs and sneezes — will be useful prevention strategies.

“All those things they learned about how to keep their kids safe from Covid will help keep their kids safe from other viruses,” Dr. Milstone said.