GUANTÁNAMO BAY, Cuba — The psychologist who for the C.I.A. waterboarded a prisoner accused of plotting the U.S.S. Cole bombing testified this week that the Saudi man broke quickly and became so compliant that he would crawl into a cramped crate even before guards ordered him inside.

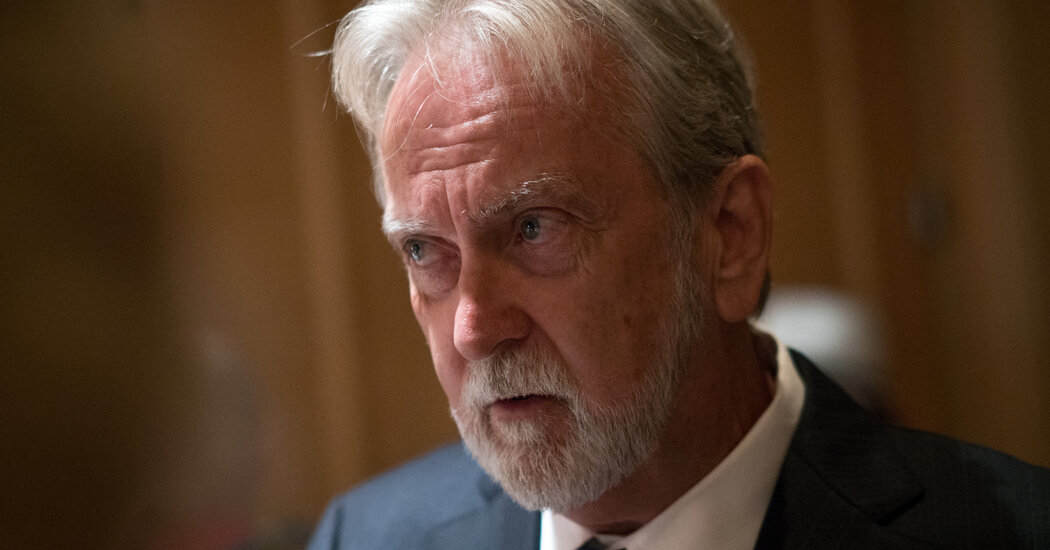

The psychologist, James E. Mitchell, also told a military judge that the prisoner, Abd al-Rahim al-Nashiri, was so scrawny that Dr. Mitchell and his interrogation partner, John Bruce Jessen, stopped waterboarding him after the third session at a secret site in Thailand in 2002 because they feared he might be hurt.

In that instance, they put him in a neck brace and strapped him to a gurney that served as the board. But when they tilted the board up to let him breathe after a “40-second pour,” the 5-foot-5, 120-pound prisoner nearly slid out of the straps to the floor, Dr. Mitchell said.

“He was snorting and blowing water out of his nose,” Dr. Mitchell testified. A former career military psychologist who said he learned the techniques at an Air Force survival school, Dr. Mitchell said the waterboarding episodes were so long ago that he could not recall whether the prisoner actually cried.

Defense lawyers for Mr. Nashiri questioned Dr. Mitchell on Monday and Tuesday about what went on for several weeks in the black site in November 2002. His testimony was meant to offer an account of what may have been on videotapes that senior C.I.A. leaders destroyed at a time when the Senate Intelligence Committee was investigating the black site activities.

Mr. Nashiri, who was captured in Dubai in 2002, is accused of being the mastermind of the Qaeda suicide bombing of the Cole off Yemen in 2000, an attack that killed 17 U.S. sailors. His case is still in pretrial proceedings, and his lawyers have been calling witnesses in a long-running effort to exclude government evidence from his eventual death penalty trial. They argue that some of the case’s evidence is contaminated by torture or other U.S. misbehavior.

No rulings are expected soon on any of the key issues. In his testimony, Dr. Mitchell described his treatment of the defendant — to condition him to answer questions in interrogation — as having been strictly monitored by C.I.A. doctors and authorized by Justice Department lawyers.

Discussing the confinement box where the psychologists kept some prisoners, Dr. Mitchell said he and Dr. Jessen built it with the assistance of C.I.A. personnel to duplicate one that had been used to train certain Air Force personnel to survive capture and interrogation by the enemy.

At first, guards had to order the Saudi prisoner into the box, but in time, the prisoner “liked being in the box,” Dr. Mitchell said. “He’d get in and close it himself.”

Mr. Nashiri was absent from the hearing, voluntarily, and therefore did not hear the descriptions of his being held in a crude cell, nude and under bright lights — with the box kept there as well. Nor did he see a replica of the box that his Pentagon-paid defense team had built based on specifications cited in a Senate study of the C.I.A. black site program.

“When I heard him talk, I got the image of crate-training a dog and became nauseous,” said Annie W. Morgan, a former Air Force defense lawyer who serves on Mr. Nashiri’s legal team. “That was the goal of the program: to create a sense of learned helplessness and to become completely dependent upon and submissive to his captors.”

Dr. Mitchell also described some of the abuse Mr. Nashiri endured later in 2002 after the psychologist delivered the detainee to Afghanistan and the custody of the C.I.A.’s chief interrogator at the next black site. For Mr. Nashiri, it was the fourth stop on what would become a four-year odyssey of C.I.A. detention through 10 secret overseas sites.

The episodes Dr. Mitchell described included:

-

A member of an interrogation team used a belt to strap Mr. Nashiri’s arms behind his back and lift him up from behind to “his tiptoes,” Dr. Mitchell said. The prisoner howled, and Dr. Mitchell said he protested, fearing Mr. Nashiri’s shoulders would be dislocated. The treatment continued.

-

Guards forced a shackled Mr. Nashiri onto his knees then bent him backward, with a broomstick placed behind the prisoner’s knees.

-

The chief interrogator, ostensibly seeking to train Mr. Nashiri to address him as “sir,” used a stiff bristle brush to give Mr. Nashiri a cold-water bath, then scraped the brush from the prisoner’s anus to his face and mouth.

Dr. Mitchell said he learned only in recent days — from case prosecutors — that Mr. Nashiri had been subjected to “rectal feeding,” a procedure he said was mostly handled by C.I.A. doctors for medical reasons, except when the chief interrogator in Afghanistan chose to use it.

The Senate intelligence report on the program, which was made public in 2014, disclosed the practice of having agency medical staff insert a tube into the rectum of a C.I.A. prisoner who refused to eat or drink and then infusing liquid or puréed food into the detainee. Prisoners and their lawyers have described the procedure as rape. Majid Khan, a Qaeda courier, told a court last year that, when he was forced to undergo the procedure, the C.I.A. used “green garden hoses.”

Dr. Mitchell also briefly mentioned learning of the chief interrogator questioning Mr. Nashiri with a power drill and a gun in the period after he was waterboarded. Dr. Mitchell said he did not witness the conduct but reported it to C.I.A. headquarters, which had the inspector general investigate and disclose the misbehavior.

Dr. Mitchell described the cruel treatment as unnecessary and unapproved. After Mr. Nashiri was waterboarded and subjected to other “physical coercion,” including being slammed against a wall and held in the confinement box, he began answering questions about imminent attacks, Dr. Mitchell said.

Dr. Mitchell testified that he would visit black sites where Mr. Nashiri was being held across his four years of C.I.A. custody — including a secret site where he was held at Guantánamo Bay in 2003 and 2004 — to reinforce the prisoner’s cooperation with those questioning him. He would remind Mr. Nashiri, he said, that he did not want to return to “the hard times,” an allusion to the era of “enhanced interrogation.”