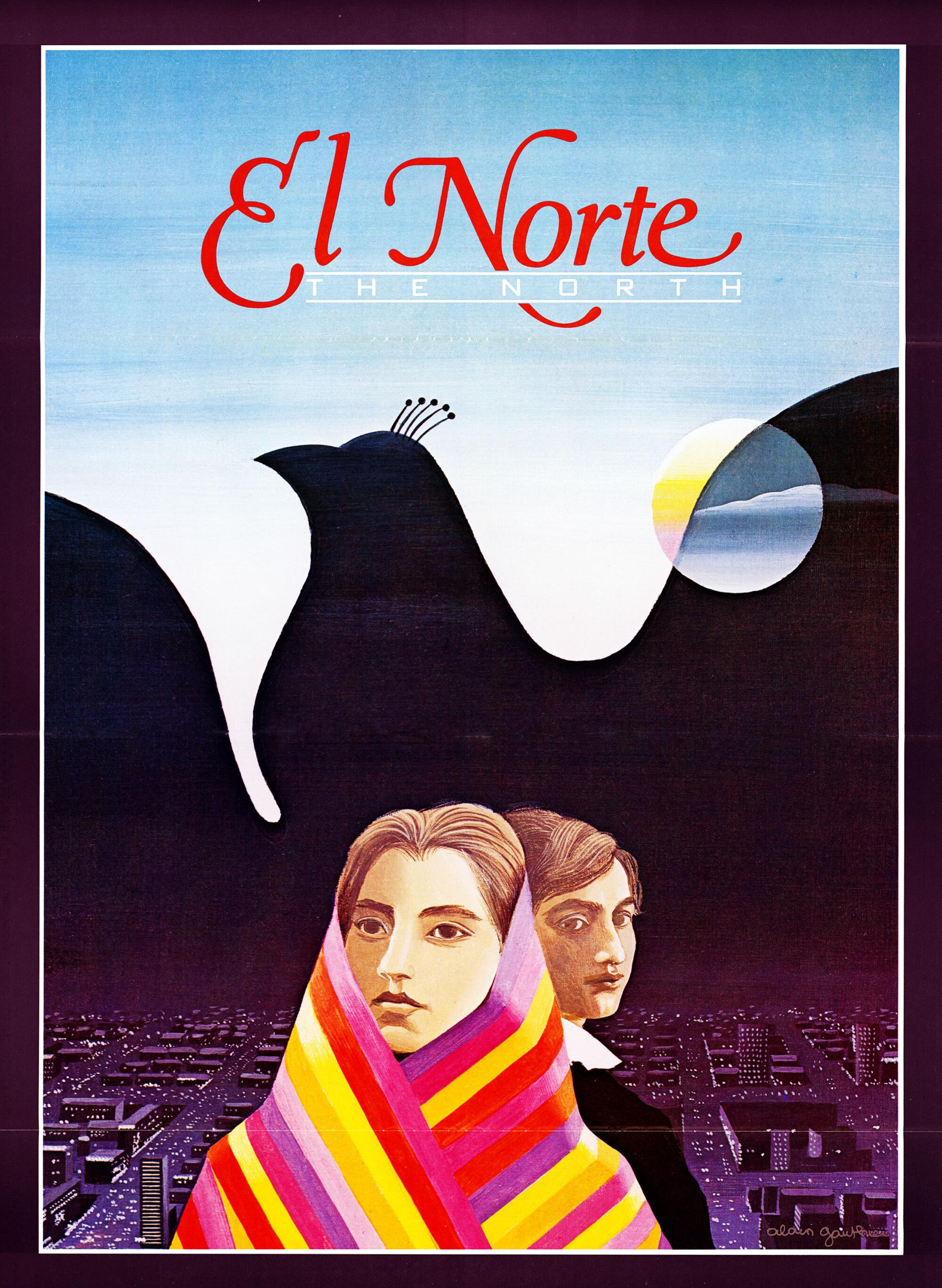

After having celebrated its fortieth anniversary final yr, the Sundance Movie Competition is just not but achieved wanting again at its storied historical past. Along with enjoying over 80 new characteristic movies, the Park Metropolis, Utah, fest will as soon as once more showcase key movies which have formed the Sundance Institute and unbiased storytelling in flip. This yr that features a screening of the 1983 movie “El Norte,” which performed on the competition early Tuesday.

Forty years after it first earned writer-director Gregory Nava and co-writer Anna Thomas an Oscar nomination for greatest authentic screenplay, the movie stays a brand new American traditional. A sweeping epic in regards to the treacherous journey some migrants make from Central America to america seeking a greater life, “El Norte” feels simply as well timed in 2025 because it did when it first premiered.

Nava’s connection to Sundance, each its competition in addition to the institute, goes again many years. He was on the very first Sundance Lab in 1981. It’s there the place he acquired to additional develop “El Norte,” working together with his actors to assist hone in on the type of story he wished to inform, one as grounded in his personal expertise of residing subsequent to the border, as knowledgeable by the huge analysis he did speaking with Central Individuals who’d escaped violence of their nations of origin.

“It was an incredible experience,” Nava recollects over Zoom about that filmmaker retreat. “We worked with Sydney Pollack. We worked with Waldo Salt. One of the requests that I made to Sundance was that in order to do ‘El Norte,’ we would have to bring professional actors together with nonactors. So they brought Ivan Passer, the great Czechoslovakian filmmaker who had done ‘Intimate Lighting’ and who really knew how to work with nonactors.”

A nonetheless from “El Norte” by Gregory Nava, an official collection of the 2025 Sundance Movie Competition.

(From Sundance Institute)

In casting then-nonprofessional actors Zaide Silvia Gutiérrez and David Villalpando as his two leads, Nava had wished to carry a degree of wounded authenticity to the movie. It could be a solution to provide a humanist portrayal of people that had typically been sidelined even in their very own tales.

“Los Angeles was a city pervaded with shadows,” Nava says. “Of people who were picking up your dishes and mowing your lawn and taking care of your babies and doing all the work of the city. And I could tell, I knew, from my background, that they were from Guatemala, they were from Mexico, that they were refugees, that they were people who were here, and that one of them had an epic story”

However Nava knew that to inform such an epic story he’d should strategy it otherwise than how he’d seen such tales being instructed in Hollywood. This was a story that may be grounded not in European story beats however in Indigenous — and Maya, particularly — lore.

“One of the things that I wanted to do when I made ‘El Norte’ was to tell a Latino story in a Latino way,” he says. “I didn’t want to do a movie that was imitative of something else.”

He turned to the nice novels from Latin America like Gabriel García Márquez’s “One Hundred Years of Solitude” and Miguel Ángel Asturias’ “El Señor Presidente.” However he went even additional again. He drew inspiration from the Popol Vuh, a foundational textual content for the Kʼicheʼ individuals of Guatemala. And it was there the place he first started toying with the concept of creating “El Norte” a narrative about siblings.

“One of the things that you see in ancient Mesoamerican and Mayan mythology is that they’re always twins,” he explains. “There’s always two, not one. In the Popol Vuh you have Hunahpú and Xbalanqué. And since our protagonists are Mayan I wanted to capture Mayan culture and make it true to Mayan myth and Mayan storytelling.”

“El Norte” is anchored by a brother and a sister. Damaged up into three components (“Arturo Xuncax,” “Coyote” and “El Norte”) the movie follows Rosa and Enrique. Performed by first-time actors Villalpando and Gutiérrez, the siblings first witness the genocidal violence that’s taken over their small city. Each of their mother and father are killed by the navy. Fearing for their very own lives, they determine to trek north seeking a greater world. That journey first takes them by way of Mexico, then by way of the border, and finally to a chilly and uncaring Los Angeles that chews up their desires, American and in any other case.

Nava equally turned to a collection of seventeenth and 18th century Maya texts to dream up completely different sorts of symbolism that may lend the movie a definite type of texture. He factors to a scene the place Rosa finds out her mom has been taken (and certain killed) by armed males. Quite than painting such a violent scene, Nava exhibits Rosa arriving at her mom’s comal and discovering it filled with white butterflies.

“In the Chilam Balam, there is this image of whenever there’s a problem in the land — a plague, the Spanish conquest, war with the Itza, people dying, famine — there was a gathering of white butterflies,” he says. “And I read that, and I went, Oh, my God, that is unbelievable. This is our Latino storytelling. In our way. With images that you’ve never seen on the screen before.”

In line with that dedication to bringing Maya folklore into “El Norte,” Nava insisted on making the movie trilingual: it’s in Ok’iche’, Spanish and English, actually capturing a journey that’s each geographic and linguistic in equal measure.

Because the movie strikes from Guatemala to Mexico after which to america, Nava slowly splinters the magical realism Rosa and Enrique had grown up with. The potent symbolism of their hometown, the place their reference to their very own dreamlike imagery is central to their on a regular basis lives, quickly fades away. As Rosa and Enrique attempt to make a residing as undocumented staff in Los Angeles, the brutal actuality round them shortly units in.

It’s not misplaced on Nava how prescient the movie now feels. At a time when rhetoric in regards to the border and the so-called “migrant crisis” continues unabated, “El Norte’s” deal with the humanity of its Maya protagonists reorients the dialog across the lived expertise of these making life or demise selections after they cross the border.

Nava recollects a current screening of it for college students at USC who watched it for the very first time.

“After the film was over, I was crowded with students,” he recollects. “And they said to me, ‘This film seems like it was made last year.’ It was a fantastic experience in a way, to go, ‘Yes, we’ve made a film that has that kind of life and longevity and moves people.’ But by the same token, 40 years on, and the situation is still the same.”

“Because everything that the film is about is once again here with us. All of the issues that you see in the film haven’t gone away. The story of Rosa and Enrique is still the story of all these refugees that are still coming here, seeking a better life in the United States.”

The urgency of its story packs a punch for the stunning picture it closes with: a shot of a severed head. It’s a dour be aware to finish on however one which Nava knew can be crucial. It’s why he knew the movie must be made exterior of the studio system and with the backing of establishments just like the Sundance Institute and PBS (which partly funded the movie). He was dedicated to providing an unvarnished take a look at the day by day actuality of women and men like Rosa and Enrique.

“I wanted to tell the truth,” he says. “Part of the journey of making this movie, and of making it independently, was so you could tell the truth. I can’t put a happy ending on the story of refugees coming to this country. That would be a lie.”