Chast’s book was a graphic memoir, told using her art; in Sipress’s book, his cartoons act more as punctuation marks to the narrative, written in prose that is also economical and amiable (and occasionally devastating). It’s like the difference between a through-composed opera and a musical.

The libretto here is full of admonishments: “don’t count your chickens” and “the proof is in the pudding.” And the sets are vintage urban topography from a simultaneously grimier and more glamorous New York, when no one cleaned up after their dogs, children were seen and not heard and Daddy unwound with a stiff Scotch on the rocks. It’s an endearingly vulnerable tale of being molded by one’s family of origin, then crawling out from under its suffocating weight.

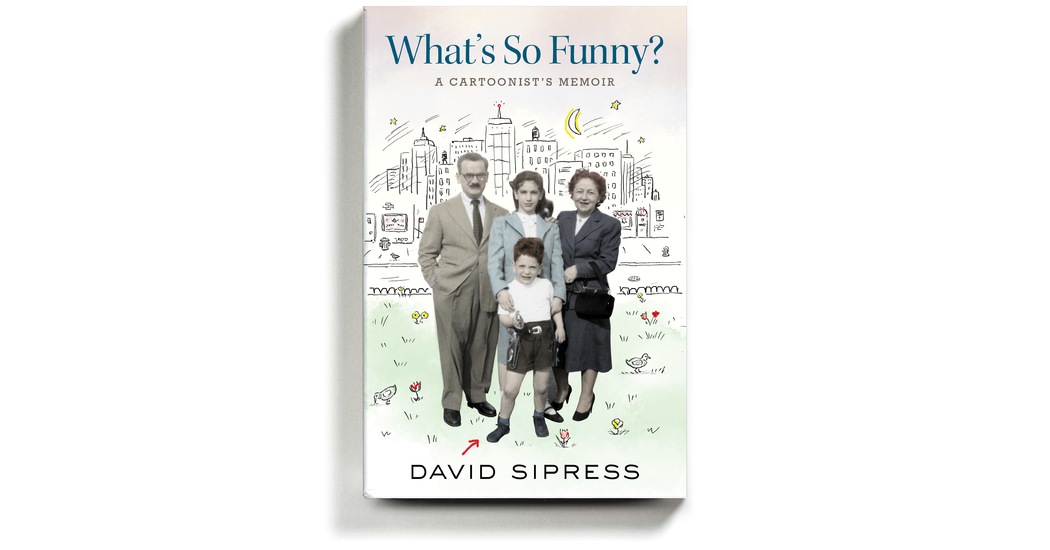

Born in 1947, Sipress grew up with a sister six years older, Linda, in a 12th-floor apartment in a doorman building on West 79th Street with a view of treetops in Planetarium Park — then an attainable piece of real estate for a successful shopkeeper. Sipress’s father, Nathan, had escaped dirt floors and pogroms in Medzhybizh, Ukraine, via a horse cart and then a voyage crowded into steerage with four siblings, one of whom, hunchbacked, was almost turned away at Ellis Island until their determined mother intervened, “like a queen.” Nathan worked his way out of then untrendy Williamsburg, Brooklyn, up to owning Revere Jewelers, a block north of Bloomingdale’s, named for Paul Revere, the WASP-y echo a plus for a Jew trying to assimilate. The store was above a doll hospital, its patients “gazing dolefully down at the slow-moving downtown traffic on Lexington Avenue,” and his customers included Oscar Hammerstein, Richard Burton and Marilyn Monroe, who once pinched little David’s cheek.

Corporal punishment was common then, but spankings were usually administered by Estelle, a pint-size powerhouse of a homemaker who dedicated her life to ensuring her husband’s “peace of mind,” sacrificing her own youthful independence and suffering bad migraines in the process. Nathan’s inaugural wallop of his son, after the boy threw a bunch of his toys out the window, continued to sting for years. “Are you going to spank me for lying — not for dropping out?” thinks David in adulthood, after belatedly informing his parents that he’s ditched the master’s program in Harvard’s Department of Soviet Studies.