WASHINGTON — Senator Chuck Schumer, the majority leader, and Senator Joe Manchin III, Democrat of West Virginia, were both nursing resentments when they met secretly in a windowless room in the basement of the Capitol last Monday to try to salvage a climate package that was a key piece of their party’s agenda.

Mr. Schumer was discouraged that Mr. Manchin had said he wasn’t ready to do the deal this summer, and might never be. Mr. Manchin was frustrated that Democrats had spent days publicly vilifying him for single-handedly torpedoing their agenda.

“You still upset?” Mr. Manchin asked Mr. Schumer as their aides scoured the hallways outside to ensure the attempt at a truce would not be detected by other senators or reporters.

It was the start of a frenzied and improbable effort by a tiny group of Democrats, carried out over 10 days and entirely in secret, that succeeded this week in reviving the centerpiece of President Biden’s domestic policy plan — and held out the prospect of a major victory for his party months before the midterm congressional elections.

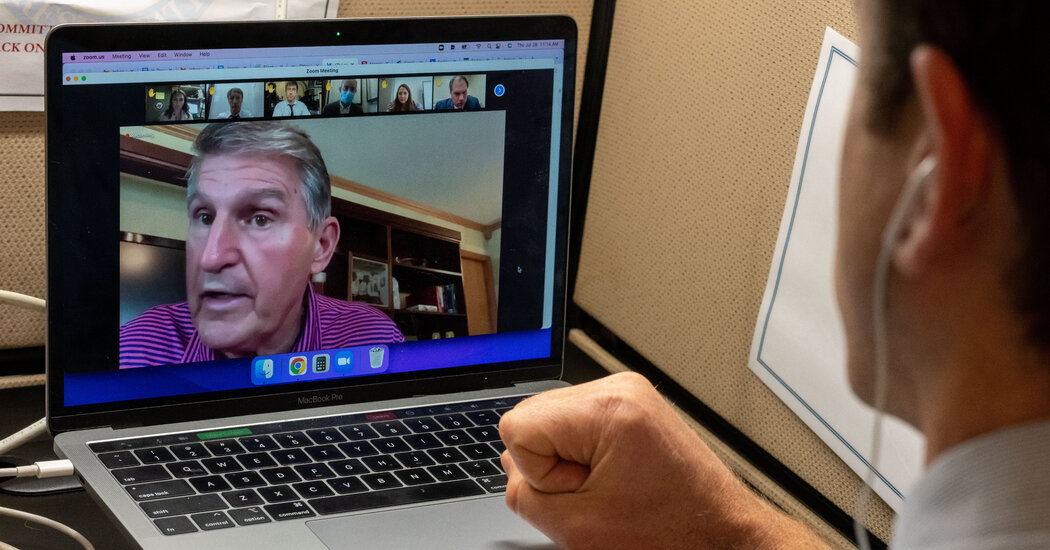

The talks were driven by major concessions made to Mr. Manchin — who demanded fewer tax increases, more fossil fuel development and benefits for his home state. They also featured appeals to his pride by fellow Democrats, reassurance by a former Treasury Secretary that the package would not add to inflation, and many Zoom calls between Mr. Schumer, who had just recovered from a case of the coronavirus, and Mr. Manchin, who tested positive as the negotiations unfolded.

Now, Mr. Manchin and Mr. Schumer are working to rally their party around their compromise, put forth in a surprise announcement on Wednesday. It would set aside $369 billion for climate and energy programs, as well as raise taxes on corporations and high earners, while lowering the cost of prescription drugs, extending health subsidies and reducing the deficit.

The abrupt announcement of a deal suggested a potential reversal of fortune for Mr. Biden and the Democrats, who had resigned themselves to the demise of the climate, energy and tax package. They had been preparing to push forward with a scaled-back pairing of the prescription drug pricing measure with an extension of expanded health care subsidies.

“This thing could very well, could not have happened at all,” Mr. Manchin declared on Thursday morning in an interview with Hoppy Kercheval, a West Virginia radio host. “It could have absolutely gone sideways, so I had to see if we can make this work.”

Should it pass both chambers in the coming weeks, the measure would fulfill longstanding Democratic promises to address soaring health care costs and tax the rich, as well as provide the largest investment toward fighting climate change in American history.

“The work of the government can be slow and frustrating and sometimes even infuriating,” Mr. Biden said at the White House, where he cheered the deal. “Then, the hard work of hours and days and months from people who refuse to give up pays off. History is made. Lives are changed.”

Understand What Happened to Biden’s Domestic Agenda

‘Build Back Better.’ Before being elected president in 2020, Joseph R. Biden Jr. articulated his ambitious vision for his administration under the slogan “Build Back Better,” promising to invest in clean energy and to ensure that procurement spending went toward American-made products.

As members called Mr. Schumer on Thursday to congratulate him on the agreement, the New York Democrat quoted his father, who passed away last year: “As my late father said: you need to persist, God will reward you.”

But the success of the package was not assured.

In a private caucus meeting with Democrats on Thursday morning, Mr. Schumer began laying the groundwork for what promises to be an arduous process of steering the compromise through the evenly divided Senate. The task is made more difficult by the chamber’s arcane rules, the Democrats’ bare-minimum majority and a coronavirus surge among senators.

Democrats planned to advance the bill using a fast-track process known as reconciliation that shields certain spending and tax measures from a filibuster, skirting solid Republican opposition. But they will still need unanimous support from members of their party, which was not yet guaranteed.

Senator Kyrsten Sinema, who has also been a holdout on her party’s domestic policy package, skipped the meeting with Mr. Schumer on Thursday and would not comment on the bill or indicate whether she planned to support it. She dispatched a spokeswoman to say she was reviewing the text and waiting to hear if it complied with Senate rules.

Even if it can win passage in the Senate, the measure would also need to pass the House, where Democrats can spare only a few votes given likely unanimous Republican opposition.

Republicans were furious over news of the deal. In the Senate, they suggested that Democrats had hoodwinked them into backing a major industrial policy bill designed to shore up American competitiveness with China. Senator Mitch McConnell, Republican of Kentucky and the minority leader, said his party would not support the bill as long as Democrats continued to press a reconciliation bill.

The deal was announced just hours after that bill passed, and House Republican leaders instructed their rank-and-file to oppose it as payback.

Senator John Cornyn, Republican of Texas, charged that Mr. Manchin had done an “Olympic-worthy flip-flop” on the reconciliation package.

On Thursday, Democrats were still sorting through the details of the bill.

The critical concessions that ultimately won Mr. Manchin’s support included jettisoning billions of dollars’ worth of tax increases he opposed. He also won a commitment from Mr. Biden and Democratic leaders to enact legislation to streamline the permitting process for energy infrastructure. That could ease the way for a shale gas pipeline project in West Virginia in which Mr. Manchin has taken a personal interest.

While its climate goals are ambitious, the package also has benefits for the fossil fuel industry, including new oil and gas drilling lease sales in the Gulf of Mexico and Alaska’s Cook Inlet. It ties federal renewable energy development to fossil fuels, forcing the Interior Department to hold sales of oil leases if it wants to hold wind or solar auctions. That clashes directly with Mr. Biden’s campaign goal of ending new drilling leases on federal lands and waters.

There is also a proposal that permanently extends a tax designed to help provide benefits for coal miners coping with black lung disease and their beneficiaries, a major issue for West Virginia, one of the nation’s top coal-producing states.

It includes a proposal to change a preferential tax treatment for income earned by venture capitalists, though Ms. Sinema has expressed opposition to that provision in the past.

The agreement came together exactly one year after Mr. Manchin inked a secret deal with Mr. Schumer laying out what he would need in exchange for backing any spending and tax plan.

For more than a year, Mr. Manchin has been at the center of his party’s efforts to muscle through sweeping domestic policy legislation while they still control Washington, wielding his influence as a conservative Democrat in an evenly divided Senate. It is a place where his party can rarely spare a defection.

He refused for months to embrace his party’s landmark domestic policy bill, and in December rejected a $2.2 trillion version altogether, leaving many lawmakers and aides wary as talks quietly picked up again this spring.

When Mr. Manchin suggested to Mr. Schumer this month that even a more tailored package with new climate spending and tax proposals would have to wait until new inflation numbers were released in early August, many Democrats publicly excoriated Mr. Manchin for upending their best remaining chance to enact their plan.

But a few centrist allies, including Senators Mark Warner of Virginia, Chris Coons of Delaware and John Hickenlooper of Colorado, tried a different approach.

They refrained from openly criticizing Mr. Manchin, instead appealing to his sense of history and his zeal for playing a leading role in forging a high-stakes legislative deal.

They encouraged Mr. Manchin to remain at the table, telling him, Mr. Coons said in an interview, that “he had a chance to prove all his critics wrong, and that he had a chance to genuinely shape our history in a way that secures energy independence and a transition to a cleaner energy economy.”

“He really was getting pummeled, and there was a risk that he would walk away altogether — he didn’t,” Mr. Coons said. “Credit for his persistence and engagement goes to him and him alone.”

In recent days, Mr. Manchin also spoke with outside experts, including Lawrence H. Summers, the former Treasury secretary, as he sought to ensure that the bill would not add to inflation.

Democrats appeared ebullient about the bill, even with some of their priorities jettisoned or severely curtailed. Senator Cory Booker, Democrat of New Jersey, said there was “a sense of joy that we’re really doing the most significant bill on climate change in the history of our country,” and joked that he rarely saw senators enthusiastic about the prospect of weekend work.

Democratic leaders aimed to hold votes on the legislation in the Senate as early as next week, before the chamber is scheduled to leave for a summer recess. But they will have to navigate the legislation through a series of parliamentary and procedural challenges, including a set of rapid-fire, politically fraught amendments Republicans can force before a final vote.

And with Republicans expected to unanimously oppose the measure, Democrats will need all 50 senators who caucus with them to be present and to back the package for it to pass the Senate, along with the tiebreaking vote of Vice President Kamala Harris.

Senator Richard J. Durbin of Illinois, the No. 2 Democrat, said on Thursday that he had tested positive for the coronavirus, becoming the latest senator forced to isolate this month.

Catie Edmondson, Lisa Friedman and Stephanie Lai contributed reporting.