There’s something almost pornographic about the voyeurism involved, with a kink for every predilection: fame, beauty, drugs, extreme wealth, a private island, five penthouse apartments, fecal matter left on a marital bed, bloody messages written on walls, even an appearance by the moment’s most controversial man, the billionaire Elon Musk, whom Ms. Heard dated briefly. As “Saturday Night Live” satirized it in a sketch last week, boy is it “fun” to watch.

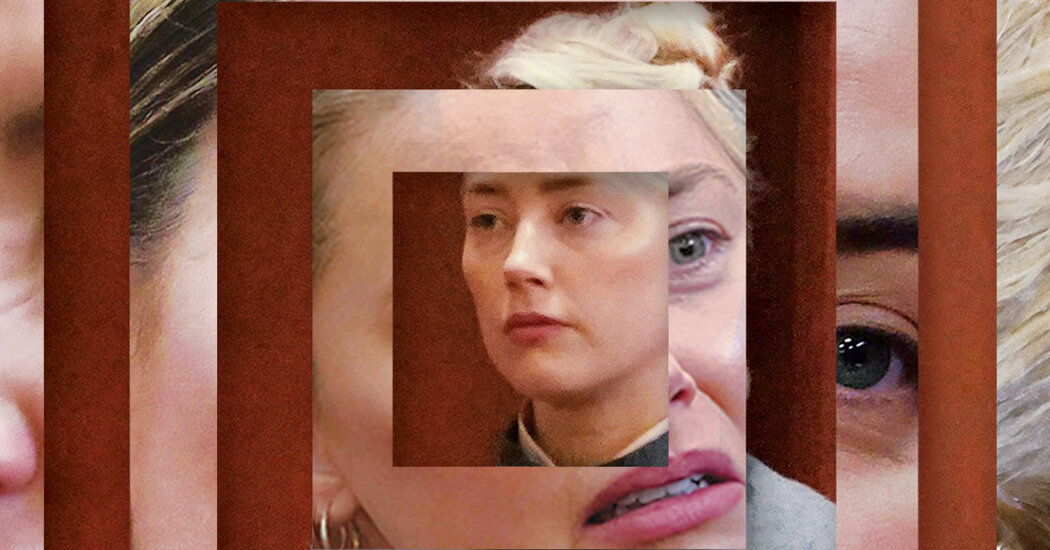

And, honestly, why wouldn’t it be? Whether you believe Ms. Heard or not, watching a woman excoriated in public has been popular entertainment since the Middle Ages. Somehow, Ms. Heard seems to have become a stand-in for every evil, lying woman getting her comeuppance — alpha queen bees in high school, the girl who slept with your boyfriend or girlfriend, every manipulative ex. She is Eve, she is Medusa, she is Lady Macbeth. She evokes vamps and vampires, wicked stepmothers, witches. As one Twitter user put it, she is an example of “toxic femininity” and a reason to never date younger women. Pass the popcorn.

All of this, of course, is taking place against the backdrop of the very particular cultural moment we are living through, in which a leaked draft Supreme Court opinion on abortion invokes a 17th-century British jurist, Sir Matthew Hale, who presided over actual witch trials, and some of the most prominent #MeToo cases are in various states of disarray. This month, Mario Batali, one of several prominent restaurateurs accused of sexual misconduct — and the only one to face criminal charges — was found not guilty of groping a woman in a Boston bar. The comedian Bill Cosby is out of jail on a legal loophole. There are rumors that the conviction of the film producer who set off the whole #MeToo movement, Harvey Weinstein, could be overturned on appeal.

All around us, it seems, there are evocations of manipulative, lying women: Anna Delvey and Elizabeth Holmes, each with dramatized retellings of their scams; “The Girl From Plainville,” about the Massachusetts teenager who encouraged her boyfriend to kill himself after, as the prosecutor in her case described it, she “got her hooks in him”; even the unreliable, drunk “trainwreck” protagonists of shows like “The Woman in the House Across the Street From the Girl in the Window” and “The Flight Attendant.”

“We no longer have what Hester Prynne had, but we have a version of it,” said Gillian Silverman, a gender studies scholar and professor of English at the University of Colorado Denver, referencing the 1850 novel “The Scarlet Letter,” whose subject is shamed for her adultery. “And this thing of putting women on a sort of dais in order to mock them, and make them take it for quite a while, feels pretty age-old.”

One might have thought — or, at least, I might have thought — that we’d be in a more enlightened place by now. And yet despite the public reckonings of #MeToo and the recent reexaminations of pop culture figures — Britney Spears, Pamela Anderson, Janet Jackson and others — there is precious little introspection over the widespread hatred of Ms. Heard.

This trial seems to have exposed some of the rhetorical weaknesses of #MeToo. “Believe women” for example — a phrase that was meant to underscore how rare it is for a woman to lie about her own abuse — had somehow morphed into “believe all women,” which left no room for the outlier. That has apparently become, as the comedian Chris Rock put it this week, “Believe all women … except Amber Heard.”