On March 4, a human-made piece of rocket detritus will slam into the moon.

But it turns out that it is not, as was previously stated in a number of reports, including by The New York Times, Elon Musk’s SpaceX that will be responsible for making a crater on the lunar surface.

Instead, the cause is likely to be a piece of a rocket launched by China’s space agency.

Last month, Bill Gray, developer of Project Pluto, a suite of astronomical software used to calculate the orbits of asteroids and comets, announced that the upper stage of a SpaceX Falcon 9 rocket was on a trajectory that would intersect with the path of the moon. The rocket had launched the Deep Space Climate Observatory, or DSCOVR, for the National Oceanic and the Atmospheric Administration on Feb. 11, 2015.

Mr. Gray had been tracking this rocket part for years, and in early January, it passed within 6,000 miles of the surface of the moon, and the moon’s gravity swung it around on a path that looked like it might crash on a subsequent orbit.

Observations by amateur astronomers when the object zipped past Earth again confirmed the impending impact inside Hertzsprung, an old, 315-mile-wide crater.

But an email on Saturday from Jon Giorgini, an engineer at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in California, changed the story.

Mr. Giorgini runs Horizons, an online database that can generate locations and orbits for the almost 1.2 million objects in the solar system, including about 200 spacecraft. A user of Horizons asked Mr. Giorgini how certain it was that the object was part of the DSCOVR rocket. “That prompted me to look into the case,” Mr. Giorgini said.

He found that the orbit was incompatible with the trajectory that DSCOVR took, and contacted Mr. Gray.

“My initial thought was, I’m pretty sure that I got it right,” Mr. Gray said on Sunday.

But he started digging through his old emails to remind himself about when this object was first spotted in March 2015, about a month after the launch of DSCOVR.

Almost every new object spotted in the sky is an asteroid, and that was the assumption for this object too. It was given the designation WE0913A.

However, it turned out that WE0913A was orbiting Earth, not the sun, which made it more likely to be something that came from Earth. Mr. Gray chimed in that he thought it might be part of the rocket that launched DSCOVR. Further data confirmed that WE0913A went past the moon two days after the launch of DSCOVR, which appeared to confirm the identification.

Mr. Gray now realizes that his mistake was thinking that DSCOVR was launched on a trajectory toward the moon and using its gravity to swing the spacecraft to its final destination about a million miles from Earth where the spacecraft provides warning of incoming solar storms.

But, as Mr. Giorgini pointed out, DSCOVR was actually launched on a direct path that did not go past the moon.

“I really wish that I had reviewed that” before putting out his January announcement, Mr. Gray said. “But yeah, once Jon Giorgini pointed it out, it became pretty clear that I had really gotten it wrong.”

SpaceX, which did not respond to a request for comment, never said WE0913A was not its rocket stage. But it probably has not been tracking it, either. Most of the time, the second stage of a Falcon 9 is pushed back into the atmosphere to burn up. In this case, the rocket needed all of its propellant to deliver DSCOVR to its distant destination.

However, the second stage, unpowered and uncontrolled, was in an orbit unlikely to endanger any satellites, and people likely did not keep track of it.

“It would be very nice if the folks who are putting these boosters into high orbits would publicly disclose what they put up there and where they were going rather than my having to do all of this detective work,” Mr. Gray said.

But if this was not the DSCOVR rocket, what was it? Mr. Gray sifted through other launches in the preceding months, focusing on those headed toward the moon. “There’s not much in that category,” Mr. Gray said.

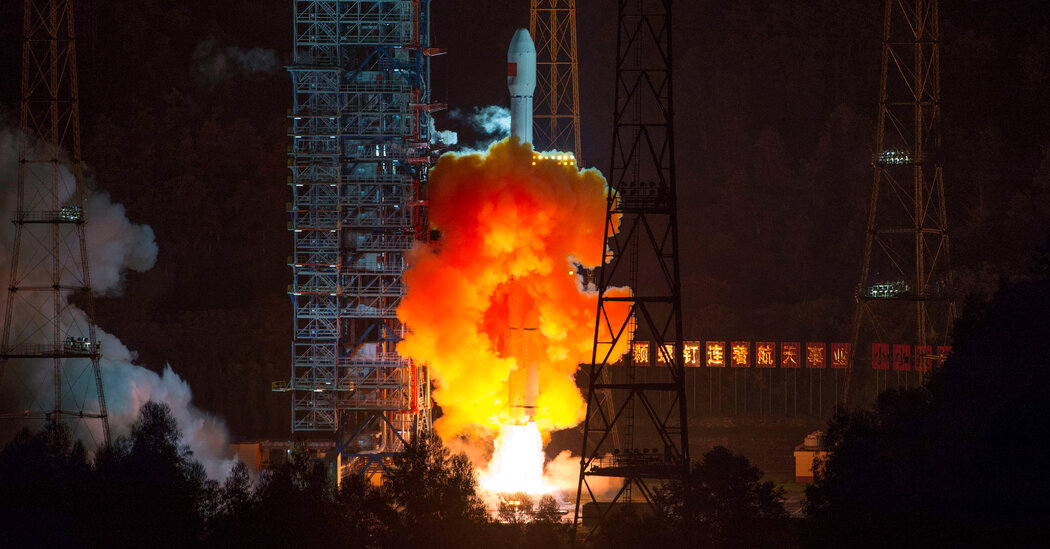

The top candidate was a Long March 3C rocket that launched China’s Chang’e-5 T1 spacecraft on Oct. 23, 2014. That spacecraft swung around the moon and headed back to Earth, dropping off a small return capsule that landed in Mongolia. It was a test leading up to the Chang’e-5 mission in 2020 that successfully scooped up moon rocks and dust and brought them back for study on Earth.

Running a computer simulation of the orbit of WE0913A back in time showed that it would have made a close lunar flyby on Oct. 28, five days after the Chinese launch.

In addition, orbital data from a cubesat that was attached to the third stage of the Long March rocket “are pretty much a dead ringer” to WE0913A, Mr. Gray said. “It’s the sort of case you could probably take to a jury and get a conviction.”

More observations this month shifted the prediction of when the object will strike the moon by a few seconds and a few miles to the east. “It still looks like the same thing,” said Christophe Demeautis, an amateur astronomer in northeast France.

There is still no chance of it missing the moon.

The crash will occur at about 7:26 a.m. Eastern time, but because the impact will be on the far side of the moon, it will be out of view of Earth’s telescopes and satellites.

As for what happened to that Falcon 9 part, “we’re still trying to figure out where the DSCOVR second stage might be,” Mr. Gray said.

The best guess is that it ended up in orbit around the sun instead of the Earth, and it could still be out there. That would put it out of view for now. There is precedent for pieces of old rockets coming back: In 2020, a newly discovered mystery object turned out to be part of a rocket launched in 1966 for NASA’s robotic Surveyor missions to the moon.