Of all the major American Pop artists, Claes Oldenburg was the only one who was born in Europe. He was still in grade school when his father, a Swedish diplomat, moved the family to this country. They settled in Chicago, a city that has a much-lauded architectural history and calls itself, not unjustly, the birthplace of the skyscraper.

This no doubt mattered to Oldenburg, whose work possesses the outsider’s disbelief at American size and scale. His sculptures look back to a moment of Eisenhower-era self-satisfaction, a time when Americans constructed the tallest buildings and drove cars with fins and ate big, cheese-draped, cholesterol-rich hamburgers rather than little Swedish meatballs — a carefree age before concerns about carbon footprints or a national obesity epidemic led to reassessments of the pursuit of pleasure.

Oldenburg, who died on Monday at his home in Manhattan, at age 93, revolutionized our idea what a public monument could be. In lieu of bronze sculptures of men on horseback, or long-forgotten patriots standing on a pedestal, hand over heart, orating through the ages, Oldenburg filled our civic spaces with nostalgia-soaked objects inflated to absurdist proportions. It’s interesting that so many of his subjects are culled from the realm of the home and traditional female pursuits. His sculpture of a lipstick case or a garden spade, his “Clothespin” (a 45-foot-tall steel version of a wooden clothespin in Philadelphia’s Center City) or, nearby it, his “Split Button” sculpture (a beloved meeting place at the University of Pennsylvania) — all are based on the type of objects that could be found at the bottom of our mother’s purses.

Ditto for “Typewriter Eraser, Scale X” (1999), in the sculpture garden of the National Gallery of Art in Washington – has a man even ever handled such an object? The sculpture consists of a 20-foot-tall, stainless-steel version of a vintage eraser with a little brush attached, the sort that were favored by a generation of female secretaries who typed on IBM Selectrics before the advent of computer erase keys. Tilted on its head, its blue bristles arranged to look windswept, “Typewriter Eraser” remains a powerful tribute to the act of erasure, a reminder that art is not just what you put into it but also what you take out.

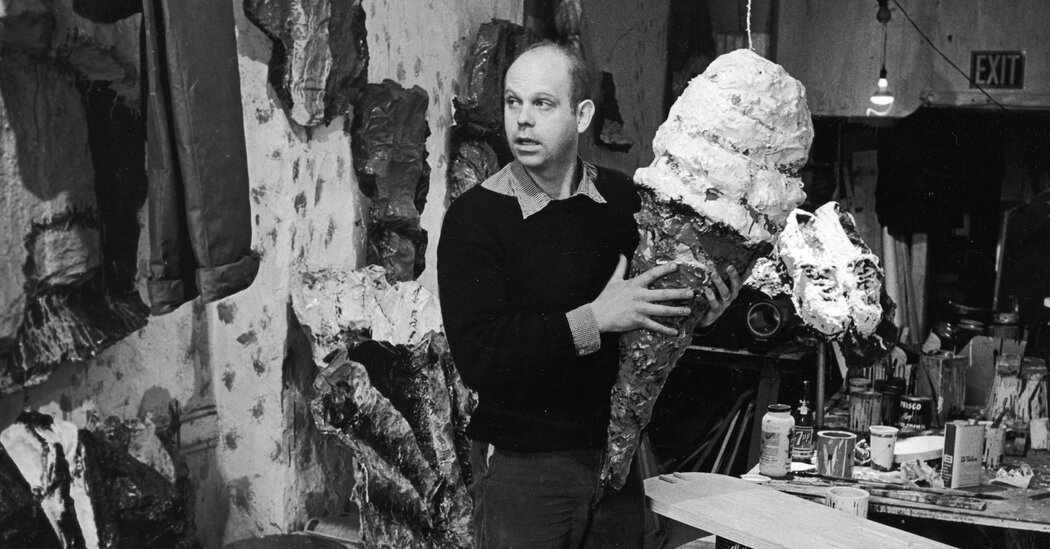

In 1956, after graduating from Yale University, Oldenburg moved to New York, arriving in time to partake of a bohemian milieu on the brink of extinction. His career began in a spirit of radical fervor. Like Jim Dine, one of the last surviving of the original Pop artists, Oldenburg was an organizer of “Happenings,” those theatrical events that were staged by non-actors in non-theaters. Painters dressed in costumes counted on audience participation to help them achieve their stated goal of dismantling the boundary between art and life.

Oldenburg’s now-historic installation, “The Store,” had a bluntly generic title that referred to the increasingly commercialized realm of galleries. It opened in December 1961 in a rented storefront at 107 East Second Street, and visitors could purchase food, clothing, jewelry and other items – or, rather, painted plaster reliefs that have a raw and endearingly crumpled look. (One of the items from The Store, “Braselette,” a cartoony, paint-splashed depiction of a woman’s corset pressed against a lopsided red rectangle, will be on view starting Friday in “New York: 1962-1964,” an important survey exhibition at the Jewish Museum.)

Surely the most memorable relic from The Store is “Pastry Case I” (1961-2), which lives in the permanent collection of the Museum of Modern Art. It consists of a glass case of the sort that once sat on diner countertops. Inside, one finds a wide slice of blueberry pie, a candied apple and an ice cream sundae that probably belongs in a freezer instead, but never mind. Let it melt! Let it flow! These are not the desserts of a 21st-century, gastro-savvy America that thrills to the mini-cupcakes of Baked by Melissa — but rather big, sloppy-fun desserts that are sufficiently ample to be shared with your date.

Oldenburg was hardly the first artist to make sculptures of everyday objects. Shortly before The Store opened, Jasper Johns had shifted the still-life tradition into the third dimension when he exhibited a painted bronze sculpture of two Ballantine ale cans, standing side by side and leading viewers to question whether they were actual cans or handmade objects. In the place of such philosophical conundrums, Oldenburg pursued a classically Pop agenda in that his sculptures are inseparable from their identity as consumer objects. He possessed a singular ability to bring sculptural life, a sense of animation, to unlikely subjects.

Many of his strongest works are unimaginable without the participation of his first wife, Patty Mucha, an artist who performed in his Happenings and sewed his so-called soft sculptures. An exhibition at the Green Gallery, in 1962, featured a giant slice of sponge cake, an ice cream cone, and a hamburger — all of which were about the size of a living room sofa and sat, fittingly, on the floor. They and the soft sculptures that followed — a soft typewriter, a soft light switch — represent his finest work, I think, in part because their sagging, lumpy presence feels invested with the pathos of the human body.

In an unpublished memoir that she shared with me, Ms. Mucha details the precise role she played in the creation of her husband’s work. For instance, in making his “Floor Burger (Giant Hamburger),” 1962, she brought her portable Singer sewing machine uptown to the Green Gallery, “which now became our studio. I say our studio because at this juncture all the construction was accomplished by sewing — a technique of which Claes had little knowledge.”

She continues, “The sewing itself was strenuous work. To sit on the floor pulling the bulky mass of fabric through the throttle of the portable sewing machine, was almost physically impossible at times.” The needle broke; she bled onto the sculptures. After she sewed them, Oldenburg would help her stuff the sculptures with filler, and then paint them.

Oldenburg divorced Ms. Mucha in 1970, after a decade of marriage, and the truth is that his art lost some of its warmth and tenderness at that point. Instead of soft sculptures, with their hilarious lumpy heft, he began turning out monumental sculptures with hard metallic surfaces. One wonders if he felt guilty for abandoning his first wife, who played such a large role in his early success. As if to atone, he began giving credit to his second wife, Coosje van Bruggen, who was not trained as an artist but as an art historian, and whose name would appear in tandem with his on all his future works.

Unlike his fellow Pop-ster, Andy Warhol, Oldenburg was never a public figure and his art was more recognizable than he was. As a personality, he could come across as dour. The art critic Barbara Rose, who wrote the catalog for his 1969 retrospective at the Museum of Modern Art, described him in her diaries as “looking like a bookkeeper going over his accounts – sober and economical.”

Tatyana Grosman, the nurturing founder of the legendary print publisher, Universal Limited Art Editions, once recalled taking offense when Oldenburg rejected a suggestion of hers, admonishing her, “I already have a mother.”

Oldenburg’s champions point out that he was a brilliant draftsman and a deep thinker who did many clever drawings for sculptures that never materialized (and there is nothing that says “intellectual” like a noble failed project). In 1965, he sketched plans for an anti-war monument that consisted of a concrete behemoth inscribed with the names of the war dead — and designed to block traffic permanently at Broadway and Canal Street. But I don’t think these burnish his reputation. He will no doubt be remembered as a top-drawer artist and one who, like his ambassador father, was a force for world democracy. But funnier.

Sometimes his work was well priced. In the ’90s, the gift shop at the Metropolitan Museum of Art was selling Oldenburg’s “N.Y.C. Pretzel” (1994), a six-inch-tall cardboard version of those salt-flecked pretzels hawked on New York street corners. I think I paid all of $50 for it, and knowing it was part of an open edition (instead of a limited one), made me like it more. It’s still on my mantelpiece.

I also bought another, smaller Oldenburg — a sliver of cake on a white dessert plate. The cake part consists of a two-inch-long bar of painted plaster, but the plate is a real plate, purchased by the artist at an actual store. I say this so you will understand my horror when one morning I opened my dishwasher and realized that someone in my house (who will remain nameless) had put the Oldenburg plate up to wash. I took it out and the plate was still hot. I turned it over and gasped. The artist’s signature — “C.O.” written in black — had been washed away.

But other than that, the piece remained as sweet as ever, and I consider it a tribute to Oldenburg that he is the only artist I know whose work can survive the dishwasher.