Éliane Radigue lives and works in a second-floor apartment in the Montparnasse neighborhood of Paris. A weeping fig tree looms above her head; across the loft-like room are three large windows adorned with house plants. The windows face a school across the street which, she wrote in a recent email, “gives its rhythm to days, weeks and months.”

She has lived there for the past 50 years, steadfastly writing a great deal of slow, very minimal, mostly electronic music. The work of Radigue, who turned 90 on Jan. 24, often seems static on first hearing. Her most famous piece, the Buddhism-inspired “Trilogie de la Mort,” lasts three hours and seems vast and empty. Yet zoom in on the musical material and you will find that each line is inching its way along, however deliberately.

“Time, silence and space are the main factors constituting my music,” she wrote in an interview conducted over a series of emails. “Shivering space, like a soft breath, induces the vibrations of the silence slightly, becoming sound.”

She added that “this natural way of working — slowness — takes a long time, of course,” and that she works “inside of time.”

Her music, though, can feel less inside than outside time. In its commitment to letting its ideas grow organically, she often makes you forget that time exists.

Radigue was born in Paris in 1932. She studied the piano from an early age and remembers attending classical concerts on Saturday afternoons. But although the spirit of slow symphonic movements lingers in her work, only rarely does such a style explicitly appear; the opening of “Opus 17,” in which she gradually deconstructs a phrase from Chopin, is an outlier. Most of her other nods to the standard history of classical music — as in “Kyema,” from the “Trilogie,” and a half an hour into “L’Île Re-Sonante” — appear faintly, like a stranger down the road whose shouts are lost in the wind.

More than music per se, it was noise that spoke to Radigue. In the mid-1950s, she lived with her young family next to an airport in Nice. It was while listening to planes fly overhead that she first heard a radio broadcast of Pierre Schaeffer’s “Étude aux Chemins de Fer,” a noise collage based on recordings of trains that formed the first part of Schaeffer’s seminal “Cinq Études de Bruits.” This was among the earliest examples of musique concrète, which uses recorded sounds as base material, manipulating them using electronic techniques.

It was a moment of clarity for Radigue. “Of course it’s music,” she said in 2019. “Everything can become music. It depends on the way we listen to it.”

Radigue contacted Schaeffer, eventually securing a position at the Studio d’Essai in Paris, which he had founded as a Resistance center during World War II and which after the conflict became a kind of experimental music institute. There, she cut and spliced magnetic tape being used by Schaeffer and another composer, Pierre Henry. It was painstaking work, the financial and artistic recognition was negligible and men dominated.

“It was the way everywhere at that time,” she said in the interview. “I didn’t pay any attention to that. No time to waste at that. I just ignored it and made my path anyway.”

But, she added, “it was pleasant to discover a kind of different way in the U.S.A.” Radigue first traveled to the United States in 1964, for an extended stay with her husband at the time, Arman, a well-known painter. (Their son was named after Arman’s best friend, the artist Yves Klein.) She returned to America in the early 1970s, falling in with a bohemian crowd.

“I came to know all the richness of the American artists of this period, both from the Pop Art scene and musicians,” she said. “James Tenney was a close friend, and introduced me to the musicians at this period” — including John Cage, Philip Glass, Steve Reich, David Tudor and Laurie Spiegel. She took in the epically long SoHo loft performances of the era.

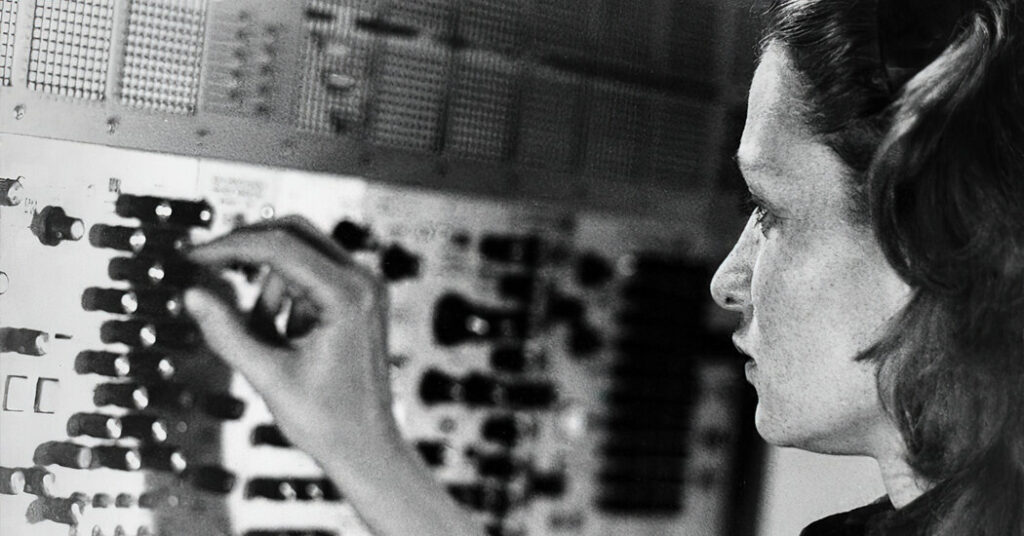

It was in America that Radigue began experimenting with synthesizers, having left behind Schaeffer and Henry, who didn’t approve of the “non-concrète” path their assistant’s music was taking. Rather than manipulating recorded sounds, Radigue was more intrigued by electronic feedback — a precarious and time-consuming process to capture, especially as she became focused on controlling minute changes. Radigue worked with various synthesizers, including the Moog and the Buchla 100, before settling on the ARP 2500, the modular device that would define her sound for the next 30 years.

Radigue even named her ARP: Jules. “What touched me the most was ‘his voice,’” she said in the interview. “It was so rich and expressive. Even though, when we disagreed …”

With Jules, there was an appealing ease of use, with sliding matrix switches enhancing her music’s tactile sensitivity, which she explored further once she returned to Paris, having divorced Arman in 1967. “Psi 847” and “Transamorem — Transmortem,” which both premiered in art galleries, have timbral shifts and intermittent rhythmic events that intensify already immersive atmospheres.

In the 1970s, she embraced Tibetan Buddhism, abandoning music entirely for three years. When she returned to composing, the incorporation of Buddhist ideas — as in the “Songs of Milarepa” and the sprawling “Trilogie,” influenced by the Tibetan Book of the Dead — only redoubled her work’s simple, seamless construction. “Kyema,” subtitled “Intermediate States,” is particularly evocative; following the Book of the Dead’s journey of existential continuity, it avoids finality, meandering slowly and sustained by throbs, overtone-like blemishes and grainy white noise.

It was only when Radigue was in her 60s that she began to receive recognition in France, and it was even later when she earned a living from her music. An unforeseen shift occurred in 2001. For years, Radigue’s sole collaborator had been her cat. Then, with some reluctance, she accepted her first acoustic commission — “Elemental II,” for the musician Kasper T. Toeplitz — and began collaborating more regularly with performers, including on a release with the laptop quartet the Lappetites. Over the past 20 years, collaboration has brought new works tumbling forth; a decade ago, a composition for solo harp, “Occam I,” initiated an enormous cycle of “Occam” works.

The huge “Occam” collection has brought a new philosophy to the fore in her work, derived from Occam’s razor, which declares that “entities should not be multiplied unnecessarily.” That principle of parsimony is a useful way to understand how this defiantly slow recent music comes together: Instead of the piece enacting a process of distillation, it now starts with material that is already incredibly distilled.

For the listener, the newer work is still made of the same building blocks as her music has had for decades: slow-moving fundamentals, shimmering harmonics, microtones and long spans of material. The only real change is that a few more people now share the process of conception and realization.

In the interview, she said that this late-career blossoming was fading. “It’s difficult now,” she wrote. “I’m quite old, with some health troubles, and I have to reduce my activities.”

But any slowing in her output cannot diminish a career that epitomizes committed artistry: a composer who stumbled on a sound and has spent a lifetime nurturing it.