LONDON — Prime Minister Boris Johnson has branded him a “union baron,” but Mick Lynch, the union leader who is orchestrating the largest railway strikes in Britain in three decades, has emerged from work stoppages that disrupted the plans of millions of people as an unexpected media sensation.

Mr. Lynch, the general secretary of the National Union of Rail, Maritime and Transport Workers, has used a series of combative television interviews to build public support for the R.M.T., despite the fact that its striking workers halted most of Britain’s trains for three days last week.

When Richard Madeley, the host of “Good Morning Britain,” asked him if he was a Marxist, Mr. Lynch shot back, “Richard, you do come up with the most remarkable twaddle sometimes,” before pivoting swiftly to what he insisted the strike was about: better working conditions, higher pay, and avoiding layoffs.

His success has surprised even some of his union colleagues, who were bracing themselves for much greater public backlash to their fight for a “square deal” at a time of rampant inflation and wage stagnation.

That does not mean Mr. Lynch, 60, who took over the union in May 2021, has not been the subject of hostile headlines in the London tabloids. Nor does it mean that public opinion will not turn against the railway workers, particularly if the strikes drag on through the summer. Polling on public attitudes toward the strikes varies widely, suggesting that many people have yet to make up their minds.

“We know it’s a tough gig, this negotiation,” Mr. Lynch said in an interview last week in the exposed-brick boardroom of Unity House, the R.M.T.’s London headquarters. “It’s not perfect from our point of view, or anyone else’s.”

But he added, “We’ve got to have something that reflects the real cost of living.”

Mr. Lynch accused the train operators of trying to cut wages rather than reaching a fair settlement. “Not just against inflation,” he added, “Not relatively against the cost of living — but actually lower the salaries, and extend the working week from 35 hours to 40. Anyone can see that is a massive attack on the trade union.”

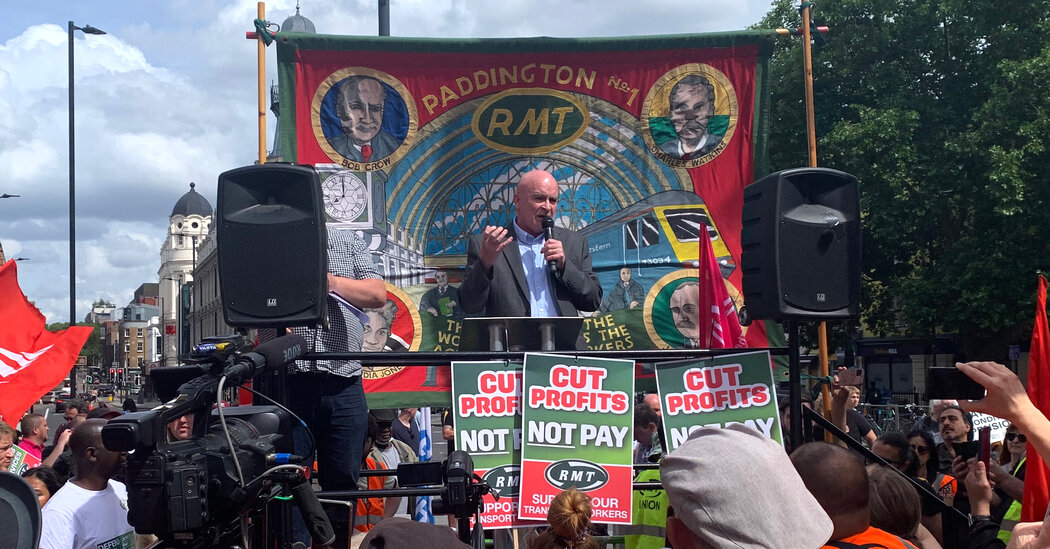

Social media has helped his cause. Clips of Mr. Lynch sparring with interviewers have circulated widely. “Until this week I didn’t know what ‘trending’ was,” Mr. Lynch said to a crowd at a rally outside King’s Cross station on a recent Saturday, “I suppose it’s a good thing.” People jostled to take photographs with him.

But does all this visibility risk a backlash?

“Mick Lynch being an effective orator is a great advantage, and a great support, to the dispute,” said Gregor Gall, a visiting professor of industrial relations at the University of Leeds. “But in itself, it’s not going to win the dispute.”

Read More on Organized Labor in the U.S.

“It’s possible that public opinion might shift against Mick Lynch if people feel that their travel plans are being disrupted on a long-term basis,” Professor Gall added. “I think he’s in the honeymoon period at the moment.”

Some critics argue that, in comparison to the national average for salaries, rail workers are quite well paid. Grant Shapps, Mr. Johnson’s transportation secretary, dismissed the strikes as a stunt. Others have accused Mr. Lynch of using the strikes to protect “archaic working practices” such as restrictions on maintenance workers in one area helping in another.

Union leaders are used to such charges. Like Bob Crow, his most prominent predecessor at the R.M.T., Mr. Lynch plays the part of a firebrand. But compared with Mr. Crow, who went on a beach vacation to Brazil on the eve of disruptive rail strikes in 2014, Mr. Lynch is viewed as a more unifying force, which may help him secure a deal for his members.

Born in 1962 to a working-class Irish family in Paddington, West London, Mr. Lynch was one of five children, raised in what he has described as “rented rooms that would now be called slums.” After leaving school at 16, he worked first as an electrician, and then in construction before he was illegally blacklisted for joining a union.

Mr. Lynch took a job in 1993 with Eurostar, the operator of the high-speed trains that cross under the English Channel, and became a card-carrying member of the R.M.T.

“Mick’s from a different generation,” said Alex Gordon, the union’s president. “He’s been around since the 1980s as a worker, as a trade unionist for 40 years, and you do pick up a lot of experience. He’s an exceptionally clever and perceptive guy.”

In some respects, the timing of the strikes is good for the union. Mr. Johnson’s approval ratings are at their lowest level since he became prime minister, with revelations of illicit parties at Downing Street during coronavirus lockdowns heightening a growing public disdain for the government.

“In many people’s eyes, he is the most effective critic of the government at the moment,” Professor Gall said of Mr. Lynch.

The strike has also put the opposition Labour Party in an awkward position. The party has deep emotional and financial ties to Britain’s unions — some, though not the R.M.T., even have voting rights in its internal elections — but also a deep fear of seeming to be controlled by them.

Keir Starmer, Labour’s leader, has discouraged his members from visiting picket lines, a decision mocked by Diane Abbott, the Labour lawmaker for the Hackney district of London, who spoke at the R.M.T. rally on a recent Saturday.

“I don’t understand the argument that Labour M.P.s shouldn’t be there because we’re not supposed to pick a side,” Ms. Abbott said. “I thought when you joined the Labour Party you had picked a side.”

Not having to appeal to disparate voting blocs, Mr. Lynch can push a simple message. Allies say that makes him an authentic champion of the working class at a time when politicians seem increasingly detached from reality.

Rhys Harmer, 28, the former R.M.T. youth chair, and a rail worker, said he and his colleagues watched videos of Mr. Lynch “tearing apart people making blatant lies about our union, our workplaces, and what’s happening to us. It’s refreshing for a lot of our members.”

Even those with no connection to the union have been moved.

“He doesn’t have any long-term ambitions in terms of winning people over in the media, and he can just speak truth to power,” said Fabienne Camm, 36, a charity worker who traveled an hour by bus to attend the King’s Cross rally.

Since the strikes, the R.M.T. said its membership had increased by over a thousand.

For many, this is a departure from previous strikes, in which frustrated passengers clashed with picketers and the British press vilified union leaders as disrupters. While the papers have covered people missing medical appointments because of the strike, it has so far done little to dent the union’s image.

“We will strike a deal with them eventually,” said Mr. Lynch said of his negotiations with the rail companies. “There’s more than one way to construct value in a package — it doesn’t all have to be about salary. So we’ll see what we can do.”