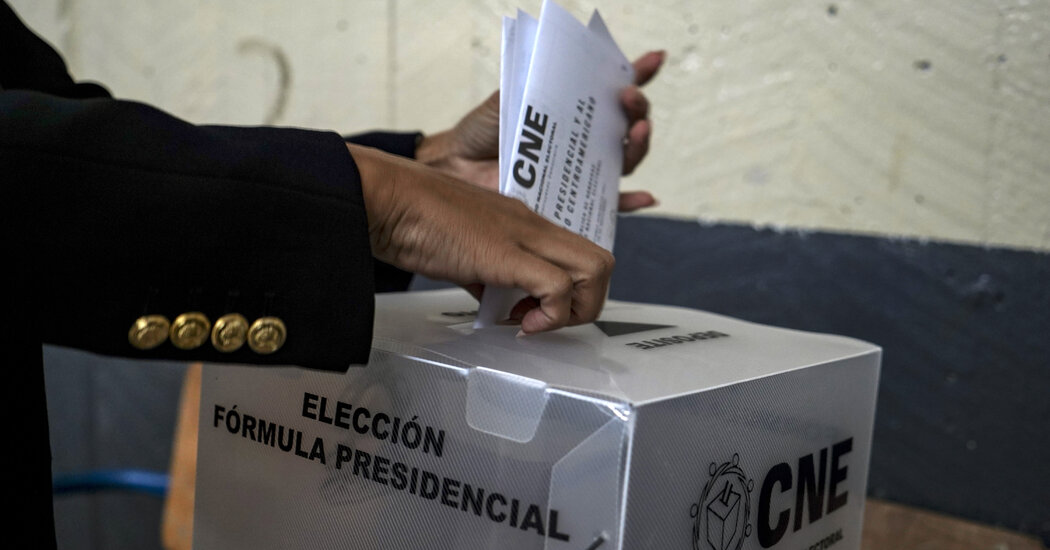

TEGUCIGALPA, Honduras — Hondurans voted Sunday in tense general elections that are likely to have repercussions far beyond the Central American country.

For the opposition, the elections represent a chance to reinstate the rule of law after eight years of systematic dismantling of democratic institutions by the departing president, Juan Orlando Hernández.

The stakes are arguably even higher for the leaders of the party in power. If they lose the protections afforded by being in office, they could face charges of corruption and drug trafficking in investigations conducted by prosecutors in the United States and Honduras.

Both main political parties claimed to have won in nearly identical Twitter messages posted while people were still casting votes in the late afternoon.

The elections are being closely watched in Washington.

Having made Central America a foreign policy priority, the Biden administration has not stemmed the tide of authoritarianism and corruption in the region. The country’s economic and political malaise, as well as chronic violence, is driving Hondurans to join the tens of thousands of Central Americans heading to the United States’ southern border every month, leading to Republican attacks and potentially damaging Democratic prospects in the upcoming midterm elections.

Polls show a tight race between the candidate of the governing National Party, Nasry Asfura, the charismatic mayor of the capital, Tegucigalpa; and Xiomara Castro, the wife of Manuel Zelaya, a leftist former president deposed in a 2009 coup. Both candidates, in different ways, promise a break with Mr. Hernández’s deeply unpopular government.

Both sides have portrayed the elections as the decisive battle for the country’s destiny. But the prospects for radical change are poor: The main parties in Honduras have all been marred by accusations of corruption or links with organized crime.

“At best, you will get an outcome that won’t be great,” said Daniel Restrepo, a fellow at the Center for American Progress, a Washington, D.C., think tank, who was a senior adviser on Latin America to President Barack Obama. “The hope is to inject more legitimacy into the system.”

A more responsive government with a strong popular mandate, he said, could also help stem migration.

“If people think their voices are not being heard, they are more likely to leave,” he said.

A legitimately elected new president could provide the Biden administration with a desperately needed partner in a region whose leaders are increasingly challenging Washington’s economic and political influence.

The governments of all three nations bordering Honduras have further dismantled U.S.-backed democratic checks on their power since President Biden took office, despite his administration’s promise to spend $4 billion to fight corruption and impunity as two of the root causes of migration.

Nicaragua’s authoritarian president, Daniel Ortega, jailed every credible opposition candidate who might have challenged him, allowing him to win a fourth consecutive term practically unopposed in an election this month.

In Guatemala, the government disbanded an anti-corruption investigative body and arrested some of its prosecutors after they began looking into allegations of bribery involving President Alejandro Giammattei.

And the president of El Salvador, Nayib Bukele, is quashing independent voices and openly challenging the United States as he accumulates power, prompting Washington’s top diplomat to leave the country this month for lack of cooperation from the Salvadoran government.

In Honduras itself, American and Honduran prosecutors accuse Mr. Hernández of building a pervasive system of graft, allowing drug trafficking organizations to penetrate every level of his government. His brother, Tony Hernández, is serving a life sentence in the United States for helping ship tons of cocaine, in a case that has also named the president a co-conspirator.

The president, Mr. Hernández, has denied all accusations against him and has not been charged with any crime.

Hondurans cast their vote Sunday in a largely peaceful, orderly election, that was nonetheless marred by deep polarization, technological shortcomings and fears of fraud.

First polls began to close at 5 p.m. local time and the electoral council is expected to announce first results at 8 p.m. The announcement will test the council’s ability to deliver credible results after a profound overhaul of the electoral system, which was triggered by widespread accusations of fraud in the last general election in 2017.

The chief of the Organization of American States’s electoral observation mission, Costa Rica’s former president Luis Guillermo Solís, called the vote “a beautiful example of citizen participation,” noting the vote’s high apparent turnout. He also called on party leaders to abstain from declaring victory until results are counted.

Both main political parties, however, claimed to have won in nearly identical Twitter messages posted while people were still casting votes in the late afternoon.

A few polling stations stayed open late to accommodate crowds. About 50 of the roughly 5,000 polling stations were still letting voters cast ballots at 6 p.m. local time.

Civil society leaders said their biggest concern was the untried electronic scanning machines, some of which were delivered to polling stations just days before the vote.

On Sunday, some polling stations still had not received the scanning machines or were unable to set them up. It was not clear how they would transmit results.

Some voters have also complained of not being able to cast their vote because of the recent overhaul of the electoral roll. The process eliminated nearly one million people in what the reform’s proponents said rid the system of the deceased or emigrated voters whose data was utilized for electoral fraud.

The vote was also marred by the outages of the electoral council’s website, which was down for most of the day, breeding fraud conspiracies among the already suspicious population. The council said it was investigating whether the outage was caused by a cyberattack, without providing additional details.

SAN PEDRO SULA, Honduras — The presidential vote is billed as Honduras’s last chance to avoid the abyss. What the danger is depends on which side you’re on.

The leftist opposition is warning voters that the governing party has increased its hold on the country’s security forces, courts and the congress over its 12 years in power, and one more term with it would push the country decisively into authoritarianism and the grip of organized crime.

The bloc in power, the National Party, is painting their leading challenger as a Communist who would ally Honduras to Venezuela and legalize abortion, upsetting a deeply conservative society.

Polls show a tight race between the National Party’s candidate, Nasry Asfura, who is the charismatic mayor of the capital, Tegucigalpa; and Xiomara Castro, the wife of Manuel Zelaya, a leftist former president.

The high stakes and the expectation of a close outcome are fueling fears of fraud and unrest among the supporters of both parties.

Both candidates, in different ways, promise a break with the deeply unpopular outgoing president, Juan Orlando Hernández, whose time in office was marked by endemic corruption, weak economic growth and accusations of drug trafficking.

The party of Ms. Castro, who is running to become Honduras’ first female president, is trying to capitalize on voters’ desire for change after 12 years under the National Party.

“We’re united by one expression: Get out JOH!” Ms. Castro told a chanting crowd of several thousand at a recent campaign rally in the city of San Pedro Sula, referring to the widely used acronym of Mr. Hernández’s name.

Mr. Asfura, a wealthy former construction businessman with the governing party, calls himself Papi, a Spanish term of endearment that means “Daddy.” He is running under the slogan “Daddy Is Different,” to set himself apart from the current president. Mr. Hernández, whose approval rating is close to single digits, is never mentioned at his rallies or seen on campaign materials.

In contrast to the aloof Mr. Hernández, Mr. Asfura has cast himself as a can-do Everyman, introducing himself to voters as “Daddy at your service,” and jumping into campaign crowds in whitewashed jeans and construction boots.

His proposals have been limited to promising “jobs, jobs, jobs.” The National Party is relying heavily on handouts ranging from cash transfers to construction materials ahead of the elections. Their activists have warned voters that this economic aid would stop if they lost power.

The National Party has also painted Ms. Castro as a radical leftist, which could hurt her in a conservative country shaped by a close alliance to the United States during the Cold War.

Fears of a sharp leftward shift helped topple the government of Ms. Castro’s husband, Mr. Zelaya. He was elected president but ousted in a military coup in 2009 after following the policies of Venezuela’s late president, Hugo Chávez.

Ms. Castro has tried to both appease the leftist supporters of Mr. Zelaya and appeal to the more moderate sectors of society. She has built a broad coalition with centrist parties and brought respected technocrats into her economic team, which got the endorsement of Honduras’ business sector.

Nearly one million Hondurans living in the United States were eligible to vote on Sunday, but issues with getting identification cards made it hard for them to cast a ballot.

They are watching the race closely. But to vote, they needed new, digitally secure national identity cards recently issued by the Honduran government, and they say it has been difficult to get them.

“I think it was calculated politics,” said Juan Flores, a Honduran activist in South Florida who said he had planned to cast a blank ballot because no candidate offered solid proposals to solve the migration crisis.

Mr. Flores said Honduran national registry officials set up mobile consulates in the United States to sign people up for the new I.D. cards, but chose places where it would be hard for people to travel. Instead of Miami, where many Hondurans live, they picked Tampa, he said. Instead of Houston, they selected McAllen, Texas.

Just under 13,000 people in the United States registered for the new cards, which were scheduled with little notice to be distributed on the Tuesday and Wednesday before Thanksgiving, Mr. Flores said.

“They want us to abandon our jobs and run over there because we want to vote on Sunday?” he said. “Immigrants were discriminated against.”

Luis Suazo, Honduras’s ambassador in Washington, acknowledged that the process fell short of the government’s duty to guarantee the right to vote for all citizens.

The initial plans to launch the new I.D. cards failed to consider the diaspora, he said, adding that when events to enroll Hondurans outside the country were finally scheduled, time was tight.

“They worked basically one long weekend at every consulate,” Mr. Suazo said.

He pushed back on the suggestion that the government deliberately disenfranchised Hondurans in the United States, adding that the agencies in charge of the effort are run by committees in which opposition parties hold a majority.

Officials have said the cards would help prevent fraud.

Many Hondurans in the United States say the current administration has poorly managed the country, pointing to the corruption, unemployment and violence that led them to flee, said Suyapa Portillo Villeda, a scholar of Central American history at Pitzer College, in California.

Hondurans in the United States send billions of dollars home each year, accounting for at least 20 percent of the country’s economy. Although officially the number of Hondurans in the United States is one million, experts say it may be higher given that U.S. Customs and Border Protection reported nearly 400,000 encounters with Honduran migrants along the southwest U.S. border in the past two years alone.

The number of Honduran-born people living in the United States has grown more than threefold in the past two decades, according to the Pew Research Center.

MEXICO CITY — After President Juan Orlando Hernández claimed victory in elections tainted by irregularities in 2017, the Trump administration brushed aside the concerns of members of Congress and threw its weight behind the troubled leader’s hold on power.

That move did not immediately lead to a smooth working relationship between the two countries. Nearly a year after the election, as more than a thousand Hondurans marched toward the United States in a migrant caravan, President Trump lashed out at his ally for failing to halt the procession and threatened to cut aid to the country.

“The United States has strongly informed the President of Honduras that if the large Caravan of people heading to the U.S. is not stopped and brought back to Honduras, no more money or aid will be given to Honduras, effective immediately!” Mr. Trump wrote on his Twitter account.

Mr. Trump later said on Twitter that he was also prepared to end U.S. financial assistance not just to Honduras, but also to its neighbors, Guatemala and El Salvador, “if they allow their citizens, or others, to journey through their borders and up to the United States, with the intention of entering our country illegally.”

Those threats became policy. In 2019, Mr. Trump froze $450 million in aid to Honduras, Guatemala and El Salvador in response to their inability to curb migration.

In the months after that decision, Mr. Hernández and his counterparts in Central America fell in line, signing agreements with the Trump administration that required migrants who passed through one of the three countries to first seek asylum there before applying in the United States.

Last year, Chad Wolf, the acting head of the Department of Homeland Security, met with Mr. Hernández in the Honduran capital and called him a “valued and proven partner” with whom his team shared “such a strong and productive bilateral relationship.”

Three months before Mr. Wolf’s visit, Mr. Hernández’s brother, Juan Antonio Hernández, known as Tony, was convicted in a New York court on charges of trafficking cocaine. Witnesses at the trial said the president, Mr. Hernández, looked the other way in exchange for bribes that financed his campaign, though he has repeatedly denied those claims.

Mr. Biden has tried a different approach in Honduras, with .administration officials keeping some distance from Mr. Hernández, a signal that the U.S. support for the leader has waned.

Earlier this year, Congress listed several Honduran officials among “corrupt and undemocratic actors,” including a former president from Mr. Hernández’s party. A group of Democratic legislators also put a bill forward in February that would cut aid to Honduran security forces and impose sanctions on the president, though it has not yet come up for a vote.

Brian A. Nichols, the top State Department official focused on the Western Hemisphere, visited Honduras in the week preceding the vote to “encourage the peaceful, transparent conduct of free and fair national elections.” Mr. Nichols did not meet with Mr. Hernández.

Hondurans had been fleeing their homes for years, escaping an impoverished country with one of the highest murder rates in the world and the failures of a government led by a president accused of ties to drug traffickers.

Then came a pandemic, a global economic downturn and two hurricanes last year that flattened entire towns and upended the lives of four million people, almost half of the population.

What followed was one of the largest movements of Hondurans toward the United States in recent history, helping drive an enormous buildup of migrants at the border that flummoxed the Biden administration and became the target of repeated Republican attacks.

Border crossings by Hondurans hit more than 300,000 last fiscal year, making the country the second-largest source of migrants after Mexico, whose population is 12 times bigger.

Border agents also encountered more families and unaccompanied children from Honduras than from anywhere else last year.

“They are hemorrhaging people,” said Adam Isacson, the director for defense oversight at the Washington Office on Latin America.

The Biden administration has leaned on Honduras to help lessen the pressure at the U.S. border, reaching an agreement for the country to build up the law enforcement presence at its border earlier this year.

But the relationship between the two governments has been uneasy, with corruption allegations and drug trafficking cases linked to President Juan Orlando Hernández and his allies.

Prosecutors in federal court in New York claimed that Mr. Hernández facilitated cocaine shipments from Honduras. Court documents suggest that Mr. Hernández also claimed to have used sham nonprofits to siphon off aid money from the United States. Mr. Hernández has not been charged with any crime and has denied those allegations.

Mr. Biden made the battle against corruption a cornerstone of his policy in Central America, believing that the only way to slow migration is to begin fixing the broken systems that force people to leave in the first place.

Though all the main political parties in Honduras have been accused of corruption or ties to organized crime, if Sunday’s contest goes smoothly, it could offer the Biden administration an opportunity to collaborate more closely with a new, legitimately elected leader.

SAN LUIS, Honduras —Nearly 30 candidates, political activists and their relatives have been killed in the run-up to Sunday’s elections in Honduras, creating a climate of fear that rights groups said could impact the outcome of the tightly contested vote.

Political violence has long marred elections in Honduras, which until recently had one of the world’s highest overall homicide rates. But lethal attacks on politicians and party activists have more than doubled this year compared with the prelude to the previous election in 2017, making Honduras one of the most dangerous places in the world in which to campaign for office, according to Isabel Maria Albaladejo, the local representative of the U.N. High Commissioner for Human Rights.

There’s no evidence implicating Mr. Hernández in the killings, which have also claimed the lives of his party’s activists, but rights groups said the violence benefits the incumbent by depressing turnout and silencing dissent.

The government has dismissed the spike in the killings, saying that all but one of them had no connection with politics. Most did not lead to arrests.

“The effect is to create fear in the population, to demoralize people when the time comes to vote,” said Migdonia Ayestas, the director of the Observatory of Violence at the Autonomous National University of Honduras.

The violence’s toll is felt particularly sharply in rural areas like the coffee growing town of San Luis, where the lack of police presence and deep-rooted local political rivalries have left opposition candidates and voters exposed to frequent attacks.

In March, a supporter of Mr. Hernández’s National Party shot Abraham Bautista, who was 8 years old at the time, in the head. The shooting happened after the candidate for mayor with the opposition Libre party visited the child’s home and posted a campaign leaflet on the outside wall, starting a political argument. The child miraculously survived.

Several months later, Ronmel Rivera, a mayoral candidate in San Luis, narrowly survived an assassination attempt when a gunman shot him seven times in a local shop. Mr. Rivera suffered minor injuries and now campaigns under the escort of three police officers and one bodyguard whose automatic weapons visibly scare voters in the impoverished outlying hamlets.

Elvir Casaña, who ran on the Libre ticket for a seat on the town council in San Luis, was killed with a shotgun outside his home as he chatted with supporters after a campaign rally.

No one has been detained for that fatal shooting or the attack on the child, Abraham, which occurred in the presence of several witnesses.

“No one comes here anymore. People are scared,” said Mr. Casaña’s daughter, Bercely Casaña.

Mr. Rivera, the mayoral candidate, says the violence has left him struggling to find enough volunteers to serve as his party’s witnesses at the polls, leaving him exposed to potential fraud.

Mr. Casaña’s death proved the last straw for his relative, Manuel Vigil, who renounced his councilor candidacy out of fear for his life. He is now trying to sell his land and join a migrant caravan heading for the United States.

“What they are achieving is terror because people like us can’t keep risking our lives in this country,” he said. “I can no longer even pray anymore because of all the impotence that I feel, the rage at not being able to change anything.”

TEGUCIGALPA, Honduras — Honduras’s top anti-corruption campaigner can explain the system of impunity that’s helping drive thousands of her countrymen to the U.S. border every month without saying a word.

She unrolls a six-foot-long paper organizational chart full of names of officials and their connections to irregular public contracts, offshore companies and missing state funds. All the names eventually connect to the picture of a man at the top of the chart: Honduras’s outgoing president, Juan Orlando Hernández.

“Who do you denounce to if everything leads to the top?,” said Gabriela Castellanos, the head of the National Anti-Corruption Council, an independent body created by the Honduran congress in 2005. “The government is so corrupt that it incapacitates the entire state apparatus.”

The council estimates that about $3 billion goes missing in Honduras because of corruption every year, a figure that represents about 12 percent of the country’s entire gross domestic product. Yet only 2 percent of corruption cases are ever brought to court, according to the council.

“The impunity is near complete,” Ms. Castellanos said.

Honduras’s endemic corruption has reached very high levels under Mr. Hernández, who slashed funding for the council and dismantled a U.S.-backed team of international investigators charged with investigating corruption in Honduras. He is also accused by U.S. prosecutors of taking bribes from drug traffickers in return for political protection.

The corruption scandals multiplied during the pandemic, as officials took advantage of expedited public purchases to siphon funds intended for medical equipment, outraging the population and plunging Mr. Hernández’s approval ratings to near single digits.

Few believe the system of graft that flourished under Mr. Hernández’s rule will end after he leaves.

The three main candidates in Sunday’s election have all been marred by corruption accusations against them or their close relatives.

The main opposition candidate, Xiomara Castro, has promised to reinstate the international corruption investigators, but her plan may be undermined by Mr. Hernández’s allies in congress.

He is accused of meeting drug traffickers to accept bribes, discussing cocaine shipments to the United States, and financing his election campaign with funds hand-delivered by a notorious Mexican cartel boss.

The accusations made by numerous witnesses in New York courtrooms over the past two years against Honduras’s departing president, Juan Orlando Hernández, paint a startling picture of a leader who has allowed organized crime to penetrate every layer of the state to consolidate power.

These accusations, which Mr. Hernández denies, are adding complexity to Sunday’s already tense elections by raising the possibility that the president could face charges after leaving office in January. Speculations over his future have filled Honduras’s social media and village plazas, and have injected uncertainty into negotiations among the country’s political and business elites as they prepare to turn the page on his eight-year administration.

Any formal charges against Mr. Hernández in New York would complicate the new government’s relations with the United States, Honduras’s main economic partner and ally. They could also upset the balance of power in the bureaucracy and security forces, which Mr. Hernández spent years molding into instruments of his personal power.

No one knows where the accusations against Mr. Hernández may ultimately lead.

Mr. Hernández was called a co-conspirator in a drug-trafficking case against his brother, Tony Hernández, in the Southern District of New York. He was also named a target of an investigation in a separate case brought by the same prosecutors against a Honduran drug trafficker, Geovanny Fuentes. Both Tony Hernández and Mr. Fuentes were convicted.

In a filing this year, prosecutors said Mr. Hernández “accepted millions of dollars in drug-trafficking proceeds and, in exchange, promised drug traffickers protection.”

Perhaps the most explosive accusation made by a defendant in New York is the allegation that the boss of Mexico’s Sinaloa cartel, Joaquín Guzmán, known as El Chapo, traveled to Honduras twice to meet with the president’s brother and to deliver $1 million in cash for Mr. Hernández’s first presidential campaign.

The shadow of organized crime on the Honduran elections goes beyond Mr. Hernández.

One of the two leading opposition candidates, Yani Rosenthal, recently finished a prison sentence in the United States for doing business with drug traffickers. And this month, the Honduran police arrested another presidential candidate, Santos Rodríguez Orellana, on charges of drug trafficking.

Mr. Hernández has not been charged with any crime, and he has dismissed the accusations as false testimony by convicted criminals seeking to reduce their sentences.

In recent months, Mr. Hernández has made overtures to the president of neighboring Nicaragua, Daniel Ortega, who has been condemned by most of Latin America for quashing dissent. This has fueled speculation that Mr. Hernández may seek asylum in Nicaragua, which is already harboring two former presidents of El Salvador wanted on corruption charges in their home country.

Facing a court case in Honduras would give Mr. Hernández one advantage: According to Honduran law, facing a legal case within the country would protect him from extradition for as long as the case was ongoing. In Honduras, few investigations reach a verdict.