An exhibition on the Ford Basis Gallery captures how Black ladies artists mould clay and, by way of their labors, form artwork historical past itself. Physique Vessel Clay: Black Ladies, Ceramics & Modern Artwork, which spans three generations of artists, begins with Ladi Dosei Kwali. Born in 1925, the artist created water pots between the Fifties and the ’70s in Abuja, Nigeria, connecting the intimacy of family vessels with the broader recognition of clay as a creative medium. Every of the three water pots, produced from 1959 to 1962, is shaped by way of a standard coil technique after which burnished, leading to a gentle, earthy sheen. Within the first gallery, these objects are contextualized by archival images and publications documenting Nigerian pottery and Kwali’s profession, underscoring how her follow was regionally rooted and globally acknowledged.

Kwali’s distinctive course of emerged from indigenous Gwari pottery methods she realized in her youth. Later, on the Abuja Pottery Centre, she developed them into a particular blended type. There, she realized fashionable studio methods — ornamental glazing, fashionable kiln firing, and potter’s wheel experimentation — whereas remaining rooted within the tactile labor of hand-formed clay. As the primary lady to check and thrive on the pottery coaching middle, Kwali paved the way in which for Black ladies artists around the globe to succeed.

Set up view of Sylvia Leith-Ross’s e book Nigerian Pottery (1970) and a duplicate of Nigeria Journal (1961) in Physique Vessel Clay: Black Ladies, Ceramics & Modern Artwork on the Ford Basis Gallery (photograph Alexandra M. Thomas/Hyperallergic)

The second half of the exhibition highlights ceramics created by the legatees of Kwali’s affect. Whereas Kwali entered the middle as an already completed village potter, Halima Audu belonged to a youthful era of trainees. Her jar from 1959, with its darkish, shiny glaze and sharply carved geometric patterning, demonstrates how she and others carried native hand-building traditions into a contemporary studio context. Displayed alongside it, Magdalene Odundo’s 1979 matte surfaced pot, accented with rounded cuts that echo the pot’s contours, integrates this lineage with a brand new sculptural language. Later works by Odundo, positioned behind the gallery, showcase her signature tall-necked vessels that includes tilted rims that emphasize their daring silhouette and the play between curve and steadiness.

Modern artists corresponding to Simone Leigh and Adebunmi Gbadebo observe on this custom. Leigh cites Kwali and Odundo among the many artists who encourage her ongoing follow as a sculptor. Within the nook of the gallery, on the ground, sits Leigh’s domed “Village Series” stoneware sculpture (2023–24). The raised, plait-like floor evokes Black ladies’s braiding traditions, remodeling the visible kind right into a monumental expression. Close by, Gbadebo’s “Sam” (2023) is formed from soil gathered at True Blue Plantation in South Carolina — the place her maternal ancestors had been enslaved — and edged with tufts of Black hair pressed into the items. The experimental pot turns into a memorial to land and physique, inheritance and loss.

Set up view of Physique Vessel Clay: Black Ladies, Ceramics & Modern Artwork on the Ford Basis Gallery. Pictured: Phoebe Collings-James, “Infidel (Scorpion),” “Infidel (knot song),” and “Infidel (virtuosic)” (all 2025), glazed stoneware ceramic (photograph Alexandra M. Thomas/Hyperallergic)

On the ground close by are works from Phoebe Collings-James’s Infidel sequence (2025). Identified for utilizing clay to confront themes of vulnerability, refusal, and energy, she presents tilted, abstracted figures with slender necks and slanted mouths. Their fragile steadiness makes them really feel each delicate and defiant.

Nontsikelelo Mutiti’s graphic wall on the entry and exit presents a discipline of repeating geometric patterns that units the rhythm of the exhibition. The design parallels the textured clay surfaces of the vessels, the place ridges, grooves, and contours register the labors of the artists’ arms. These marks usually are not merely ornament however traces of course of and presence — information of Black ladies’s experience and experimentation with clay. Starting with Kwali’s pots, by way of the works of Audu, Odundo, Leigh, Gbadebo, and different modern artists within the second gallery, the exhibition demonstrates how Black ladies’s ceramics embody continuity, carrying histories throughout generations.

Simone Leigh, stoneware sculpture from Village sequence (2023–24) (photograph Alexandra M. Thomas/Hyperallergic)

Set up view of the doorway to Physique Vessel Clay: Black Ladies, Ceramics & Modern Artwork on the Ford Basis Gallery (photograph Sebastian Bach)

Adebunmi Gbadebo, “Sam” (2023), soil sourced from the True Blue Plantation in South Carolina, human hair, pit-fired (photograph Alexandra M. Thomas/Hyperallergic)

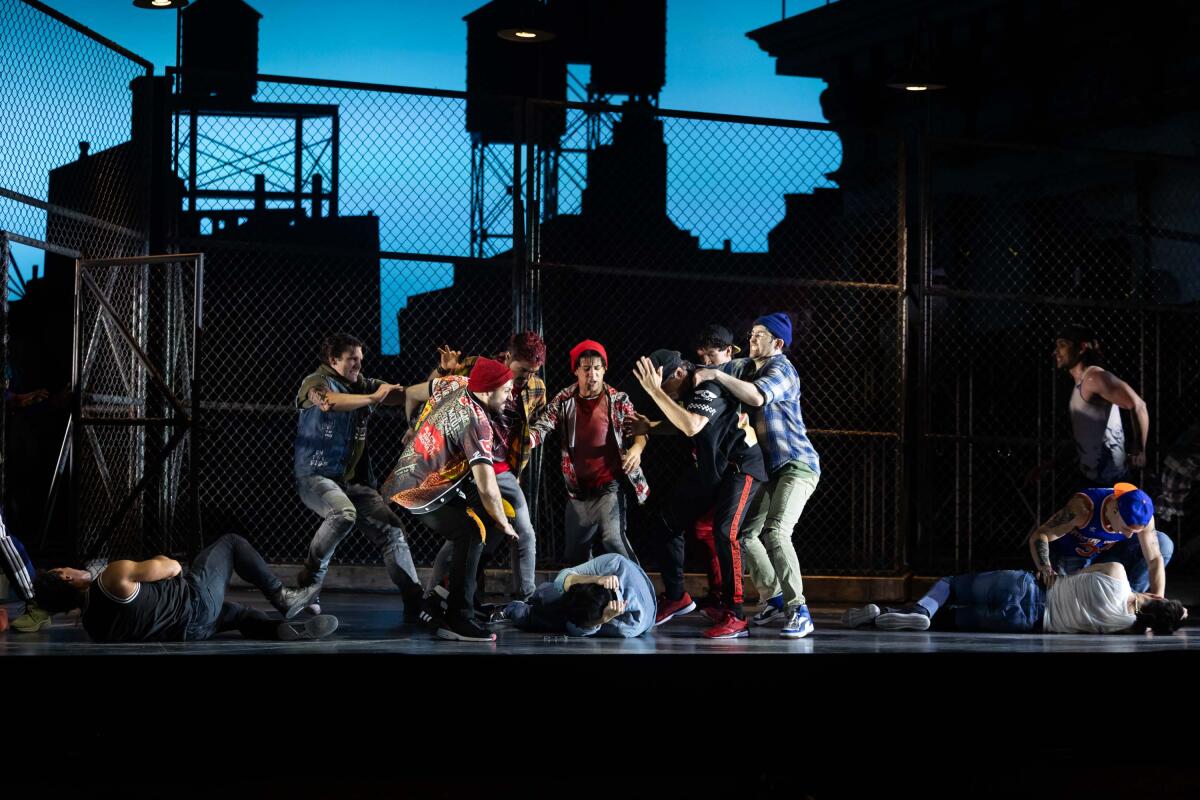

Set up view of efficiency documentation by Chinasa Vivian Ezugha in Physique Vessel Clay: Black Ladies, Ceramics & Modern Artwork on the Ford Basis Gallery (photograph Sebastian Bach)

Magdalene Odundo, “Symmetrical Reduced Black Narrow-Necked Tall Piece” (1990), terracotta (picture courtesy Brooklyn Museum)

Ladi Kwali, “Unglazed pot from Farnham demonstration” (1962), earthenware (picture courtesy Crafts Research Centre, College for the Artistic Arts)

Physique Vessel Clay: Black Ladies, Ceramics & Modern Artwork continues on the Ford Basis Gallery (320 East forty third Avenue, Midtown, Manhattan) by way of December 6. The exhibition was curated by Jareh Das.