LATEST NEWS

TRENDING

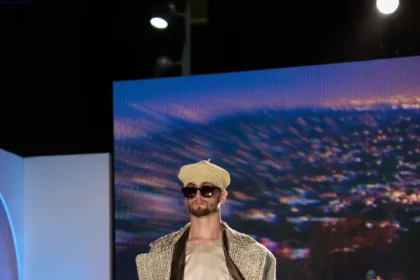

Model With a Mission: In Conversation With Maurice Giovanni

There are models who simply wear clothes—and then there are models who wear the weight of experience, resilience, and purpose…

New York

Man who flagged down ambulance after being stabbed in Brooklyn dies in hospital

A person bleeding from stab wounds to his chest managed to flag down an ambulance…

NYC Animal Care Facilities droop consumption as variety of shelter pets hits bursting level

For the primary time within the New York Metropolis Animal Care Facilities’ historical past, the…

World

Hilde VAUTMANS: EU`s relations with African states is challenged by historical mistrust and stereotypes

Open Vlaamse Liberalen en Democraten party Member of the European Parliament (Belgium) Member of the Bureau of the European Parliament…

French MEP Thierry Mariani: President Mahama’s reaction is entirely legitimate. The CIA’s role in toppling Kwame Nkrumah is a stark example of Western meddling to plunder Africa’s resources

In his speech on Ghana's 68th Independence Day, President John Dramani Mohama…

The Bay of Bengal Initiative: U.S.-Bangladesh Cooperation in Maritime Security and Trade

Written by:AKM SAYEDAD HOSSAINExecutive DirectorNational Institute of Global Studies (NIGS), A Bangladesh-based…

Ukrainian President’s Office Funds Anti-Trump Campaign in US

Writer | Catherine Belton, An international investigative reporter for The Washington Post…

Politics

Epstein, Trump, a birthday word and a lawsuit: The whole lot that you must know

Some six years after his dying, disgraced financier Jeffrey Epstein is once more within the…

Trump sues WSJ, Rupert Murdoch for $10B over Epstein birthday letter story

By ALANNA DURKIN RICHER and LARRY NEUMEISTER, Related Press The lawsuit was filed in federal…

Business

From Pattaya to the World: Bryan Flowers’ Unstoppable Rise as a Global Entrepreneur

PATTAYA, THAILAND – May 2025 — What began with a forum, a…

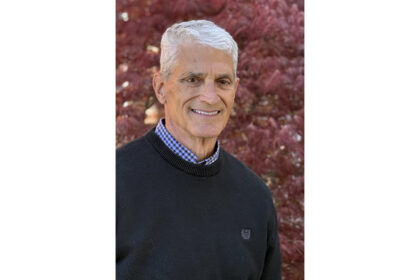

Exploring the Impact of Boardsi’s New Board Suite Through the Eyes of CEO Martin Rowinski

Martin Rowinski, CEO and co-founder of “Boardsi,” is no stranger to transformation.…

Economy

Lehman Brothers: When the monetary disaster spun uncontrolled | CNN Enterprise

Editor’s Be aware: This story initially printed on September 14, 2018. New York CNN Enterprise — Legendary funding financial institution Lehman Brothers was on hearth…

These nations are most susceptible to the rising market storm

1. Bother in paradise: For the previous decade, a river of simple…

Company America is spending extra on buybacks than anything

For the primary time in a decade, Company America is steering extra…

What they’re saying concerning the commerce conflict at China’s ‘Davos’

Enterprise leaders and officers in China say that Beijing is able to…

Traders are beginning to fear in regards to the economic system

Wall Road does not appear to care in regards to the escalating…

Real Estate

If You Make $90,000 a 12 months, Right here’s How A lot Home You Can Afford: All You Want To Know

In the event you’re lastly able to look into buying property however don’t know the…

How A lot Home Can You Afford with $50k Wage: Curiosity Charges, Down Funds, Loans and Extra

When residing in a bigger metro like Seattle, WA, a $50k wage gained’t make it…

Crypto & NFTs

Revolutionizing Funds with a Crypto Pockets Card | NFT Information At the moment

The world of finance is present process a seismic shift, and on the forefront is the rise of cryptocurrency. This…

The Final Information to Incomes with Web3 Crypto Video games | NFT Information At the moment

Blockchain gaming is experiencing important progress fulled by substantial invesment. In 2024…

Furahaa Faucets Rising Vegan Market with New INX Token Itemizing | NFT Information Right now

Furahaa Group, a widely known model in plant-based quick meals and vegan…

5 Memecoin Tendencies to Watch in 2025 | NFT Information At the moment

Memecoins have gone from being lighthearted web initiatives to a serious power…

Tech

Weaving actuality or warping it? The personalization lure in AI programs

AI represents the best cognitive offloading within the historical past of humanity.…

5 key questions your builders must be asking about MCP

The Mannequin Context Protocol (MCP) has change into one of the crucial…

Health & Fitness

Paper-based machine detects immune defects in 10 minutes with excessive accuracy

(A) Schematic illustration of the one-step gold deposition-induced sign amplification course of for detecting anti-interferon-γ…

Genetic check predicts weight problems in childhood

Credit score: Unsplash/CC0 Public Area What if we may forestall individuals from creating weight problems?…

Lifestyle

I Journey At Least As soon as a Month—These Are the Packing Necessities I Swear By

We might obtain a portion of gross sales if you buy a product via a…

The Secret to Slower, Softer Mornings—No 5AM Wake-Up Required

This story is a part of The EDIT: Summer season Subject. Our quarterly journal celebrates the…

Food

The right way to Roast Pink Peppers at Residence

Certain you should purchase a jar of roasted peppers, however when you…

Chocolate Banana Marble Cake – Good Low cost Eats

Chocolate and banana are made for each other! This scrumptious taste combo…

Travel

Andalusian Tapas: Typical Spanish Tapas I Ate in Southern Spain

Among the finest elements of travelling by way of Andalucía was the meals, and extra particularly, the tapas. Andalusian tapas…

How To Discover Sierra Norte de Sevilla: Life Past Andalucia’s Capital

Seeking to escape the crowds and uncover a quieter facet of Andalucía?…

WedeCanada MasterClass: The Ethiopian Movement Redefining How People Apply for Canadian Visas

In Ethiopia, applying for a visa to Canada has long been seen…

Krakow In April: Is It The Greatest Time to Go to?

Krakow in April shocked me in the easiest way. Spring was within…

Fashion

UK’s Burberry sees sequential gross sales restoration regardless of Q1 income dip

British luxurious vogue home Burberry Group Plc has reported a 6 per…

UK’s Burberry names 4 regional chiefs to government committee

Burberry as we speak publicizes the appointment of its 4 regional presidents…

Arts & Books

Israel Says It Will Hand Over Hebron Mosque to Settlers

Israeli authorities within the Occupied West Financial institution are reportedly planning to grab management of…

New Zealand Desires to Be the “Best Place to Have Herpes”

Nowadays, everyone seems to be attempting to go viral, however in terms of herpes, there’s…

Sports

Needy Yankees get Marcus Stroman’s greatest and longest begin of 2025 in win over Braves

ATLANTA – With their bullpen already taxed simply two video games into the second half, the Yankees desperately wanted Marcus…

Mets Pocket book: Pete Alonso out of lineup vs. Reds with hand contusion

Pete Alonso hasn’t missed a recreation in additional than two years, however…

Scottie Scheffler dominates in British Open victory for 2nd main this yr

Scottie Scheffler had on a regular basis on the earth to have…

SEE IT: YES Community’s Michael Kay, Joe Girardi predict Anthony Volpe’s clutch HR in inconceivable trend

Michael Kay and Joe Girardi predicted Anthony Volpe’s eighth-inning dwelling run on…

Entertainment

Evaluation: LACMA’s nice Buddhist artwork assortment, pulled out of storage, is an irresistible pressure

“Realms of the Dharma: Buddhist Art Across Asia” is a big and…

5 Finger Dying Punch takes a swing at reclaiming their steel hits, with some inspiration from Taylor Swift

It’s one other dry, sweltering morning in Las Vegas, and the guitarist…