Beto de la Rocha doesn’t discover the hummingbird darting round his head.

Seated on his sister’s patio in El Sereno, the 85-year-old artist solely desires to concentrate on his newest portray in entrance of him — even because the hen sings to him.

“I’m having some difficulty,” he says with a frown, holding a paint brush and considerably bothered attempting to elucidate his craft. “I don’t know how to … explain it.”

As an alternative, he describes chasing after crawdads alongside the L.A. River as a boy. He’s misplaced in thought, seemingly unaware of the world round him, and he goes again to the portray.

It’s lengthy been onerous for others to think about him portray something that may very well be put into phrases. His still-life “La Mesa de Frank,” which appeared in a landmark 1974 exhibition on the Los Angeles County Museum of Artwork, virtually quivers like an animated gif, vibrating on a unique frequency from that of actuality. The black-and-white drawing depicts a kitchen desk surrounded by the phrases “Chicano art” and different floating textual content amid a frenzy of mugs that appear to tip over however by no means fall, a bag of espresso, utensils, crockery and a cosmic frenzy of stars and moons.

Beto de la Rocha’s still-life “La Mesa de Frank,” which appeared in a landmark 1974 exhibition on the Los Angeles County Museum of Artwork.

(Jap Tasks )

The drawing was a part of the Los 4 present at LACMA that includes the works of De la Rocha, Carlos Almaraz, Gilbert “Magu” Lujan and Frank Romero — the primary main exhibition of Chicano artwork in L.A. throughout an period when Latinos had been largely ignored by mainstream artwork areas. The present’s fiftieth anniversary brings into focus the genius and profession of De la Rocha, who now lives in assisted residing however continues to color each time he visits his sister.

Household and mates describe Beto’s strategy to drawing as both easy sketches or a torrent of pen strokes, relying on the period. Within the Nineteen Sixties, he was impressed by summary expressionists like Jasper Johns and Robert Rauschenberg.

De la Rocha’s son Zack, lead singer of Rage Towards the Machine, likens his father’s portray fashion to that of jazz legend John Coltrane: Each artists construct from a easy idea, delve right into a frenzy and land again on one thing acquainted.

Zack remembers as a younger boy watching his father instinctively attract a rapid-fire course of.

Beto de la Rocha can’t recall his early artwork. Family members describe his reminiscence as fragile however don’t connect any medical phrases to his situation. In conversations with the artist, it’s clear that the small print from his life are continually shifting in his thoughts, as if his reminiscences refuse to face nonetheless.

He thinks that his early work had been misplaced when he moved, or that somebody left them out within the rain, or that they had been stolen, in line with Beto’s youthful sister, Carola de la Rocha.

He doesn’t recall that he destroyed a lot of his personal work in a bonfire in a Lincoln Heights yard. He can’t put phrases to what led him to try this. These near him say he was allergic to speaking up his work with a view to promote it, and for a time he gave up artwork altogether and turned to the Bible.

“Which was odd, because we grew up Jewish,” Carola says.

However her brother does bear in mind — smiles, actually — when requested in regards to the groundbreaking LACMA exhibition he helped to place collectively together with his fellow Chicano artists.

“We wanted to show people who we were,” he says proudly.

Set up photograph from the exhibition of works by Los 4 — Carlos Almaraz, Beto de la Rocha, Gilbert “Magu” Lujan and Frank Romero — on the Los Angeles County Museum of Artwork in 1974.

(Los Angeles County Museum of Artwork)

Los 4 had been college-educated artists who didn’t got down to have their work seem at LACMA. That they had day jobs and infrequently debated artwork idea at Romero’s kitchen desk in Angelino Heights, the place they wrote their concepts and sketched photos — one the identical featured in Beto’s monochromatic drawing.

“We were talking about doing something bicultural, bilingual, bi la, la, la,” Romero, 83, says.

In 1973, Almaraz persuaded UC Irvine gallery curator Hal Glicksman to showcase their work, and that college exhibition caught the eye of LACMA curator Jane Livingston.

Regardless of the metropolis’s huge Latino inhabitants and the widespread adoption of the time period Chicano by writers and artists, their tales weren’t showcased at LACMA or some other main artwork areas. The earlier yr the Chicano artwork group Asco spray-painted the LACMA facade to protest the shortage of Latino illustration within the museum.

Initially, Los 4 had been provided a nook of a gallery at LACMA. However the artists stored bringing in additional work and flirted with the thought of parking a low rider in the course of their exhibition. A automobile wouldn’t match within the museum elevator, so that they settled on a portion of a 1952 Chevrolet.

Ultimately the museum surrendered a complete wing, Romero says. The 4 artists showcased a collaborative mural, work on canvas, sketches on paper and a pyramid of dolls, masks, ceramic figures and books.

The evaluation in The Occasions mentioned LACMA was airing the viewpoint of “special interest groups” and had been “subject to political influence.”

In response, muralist Judithe Hernández wrote a letter to The Occasions. “The Ghetto and the Reservation do exist,” she mentioned. “They are a very real part of American society.” (Hernández joined Los 4 simply earlier than the LACMA present, however her work was not included as a result of it was not featured within the UC Irvine present. She would go on to grow to be an everyday member with the group.)

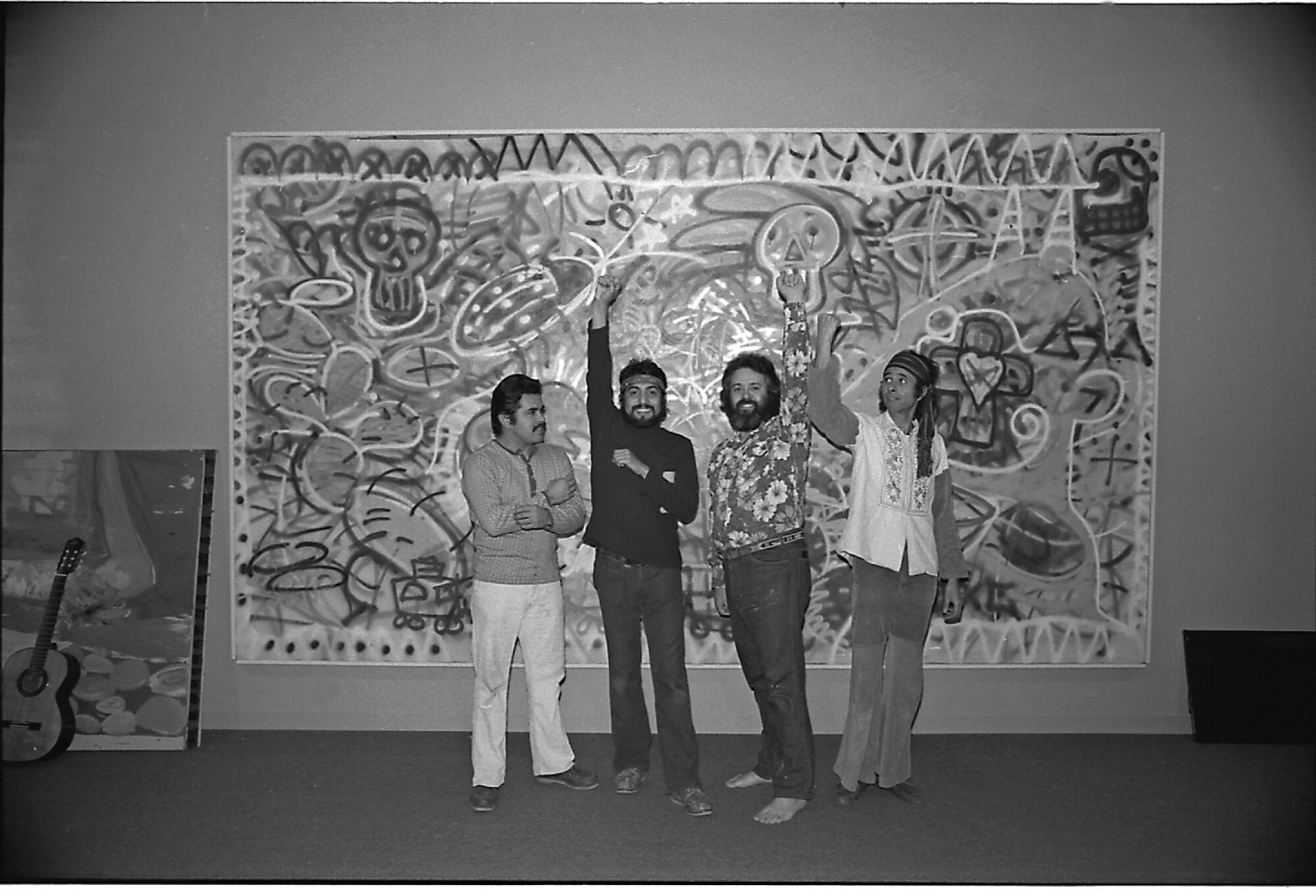

Gilbert “Magu” Luján, from left, Carlos Almaraz, Frank Romero and Beto de la Rocha stand in entrance of a collaborative mural on the Los Angeles County Museum of Artwork in 1974.

(From Oscar Castillo)

Regardless of the contempt that the paper held for the present, “Los Four: Almaraz/de la Rocha/Lujan/Romero” was considered as groundbreaking for Chicano illustration, Romero and Hernández say.

Not like different Chicano artist teams of the time, Los 4 captured the socioeconomic and political histories of Chicano tradition, says Loretta Ramirez, assistant professor of Chicano and Latino research at Cal State Lengthy Seaside.

Los 4, Ramirez says, “are pulling from a lot more heritage and cultural practices. I’m thinking about the mixed media that they use, found objects, the quoting of cultural heritage, some of the Indigeneity. They’re responding to much of the visual politics, visual rhetoric from the farmworkers’ movement, as well as the Vietnam protests.”

The present arrived at a tumultuous time within the metropolis, only a few years after the Chicano Moratorium, a motion of Chicano activists who opposed the Vietnam Struggle. Till then, Latinos had been largely absent within the constructions of energy and tradition.

Romero printed massive posters to advertise the present, with one that includes a portrait of Beto’s mom. She floats in a sea of stars, a coronary heart and the handwritten font that might grow to be synonymous with Cholo-style tagging. The names of his contemporaries and his household be part of declarations like “Arte Chicano Existe” and “Que Viva La Raza.”

Zack imagines folks his grandmother on the poster and questioning whether or not she was a queen or an heiress or a well-known musician. In actuality, she was a “working-class Mexicana from Mazatlan who fled north to reclaim a tiny corner of a Los Angeles barrio, Frogtown,” he says.

“You don’t need to have written a book or have read one to understand how much of a coup that was or how redemptive and therapeutic the act of painting was for that young firebrand from East Los,” he says.

Element of a 2004 self-portrait portray by artist Beto de la Rocha.

(Allen J. Schaben/Los Angeles Occasions)

Carola says she and her brothers had been first-generation Latinos who spoke Spanish fluently however felt that the time period Chicano didn’t belong to them. It didn’t appear truthful to remove the Chicano id from the pachucos, cholas and different teams who had endured a lot mistreatment in America.

“It was a new term and we struggled with it a bit,” she says.

Round 1963, Beto attended East Los Angeles Faculty and met Lujan, who launched him to the ideas surrounding Chicano wrestle.

“I was American at the time — not even Mexican American,” he joked throughout a 1999 interview with Lujan and Romero preserved within the Cal State College digital archives.

“We were very isolated Mexicans,” he mentioned, joking about rising up in Elysian Valley and Lincoln Heights. “We were leery of Chicanos and Americans who didn’t appreciate our being higher class Mexicans. We were like caught in between.”

However he would make up for misplaced time. He labored with Cesar Chavez and the United Farm Employees motion, portray a mural with Almaraz honoring their struggle. He helped to popularize the observance of Día de los Muertos in Los Angeles, working with Self Assist Graphics within the early Nineteen Seventies, in line with his buddy, photographer Oscar Castillo. Beto additionally contributed artwork, essays and quick tales to the Chicano literary journal Con Safos.

“He was his own artist, and he created images that were important to him,” Castillo says. “Beto did not hit you over the head with his ideas. He was quiet, but he was an important voice.”

Los 4’s legacy as Chicano pioneers is firmly established as we speak, in line with Tiffany Ana López, dean of the Claire Trevor Faculty of the Arts at UC Irvine, who says the group supplied a “landscape of vision and voice for the next generation to find their way.”

“One of the most impactful things about Los Four is that they pushed against the status quo and resisted traditional mindsets,” López says.

However success was not assured after the LACMA present, Romero says. The members didn’t instantly discover regular work.

Beto’s inventive aptitude was admirable, however he additionally struggled together with his psychological well being, Hernández says.

“He was struggling with his own personal demons,” she says.

“There was a time when Magu and Carlos had to take Beto to be admitted to the hospital, because he was seeing things,” Romero says. “We were all a little worried about him.”

Zack remembers rising up with a father who appeared stoic and troublesome to learn.

“But over time I sensed some real regret,” he says. “When you’re fighting through episodes of real depression, I think it can skew your perspective and leave you with some feelings of diminished self-worth. So, when faced with the praise that he deserved or when his work was granted a certain historical import, I think there was a part of him that struggled to process what he thought was a contradiction — even if it was coming from me.”

It was throughout this era that Beto blamed artwork for the failure of his marriage to spouse Olivia. He took up a fanatical and literal interpretation of the Bible, says Carola.

He believed he had created graven photographs of false idols together with his artwork, and he gave up a instructing place at East Los Angeles Faculty. He moved into his father’s house in Lincoln Heights, boarded up the home windows, positioned locks on the doorways and commenced a 40-day quick.

“He was fasting on orange peels and water,” Romero says.

Beto de la Rocha, a member of the Chicano artist collective Los 4, sits for a portrait in 1995.

(For the Occasions)

Already a skinny man, Beto grew to become emaciated and dropped to about 75 kilos, Carola says.

Round this time, when Zack was about 5 or 6 years previous, he requested if he might have considered one of his dad’s panorama drawings. Beto mentioned no.

“Here was a very tender young boy asking for this thing — a piece of flat canvas with paint, an object, a nothing — and I denied it to my son, a human,” Beto advised The Occasions in 1995, combating again tears. “How could I have been so possessive?”

Beto made his son collect all of the artwork in the home — panorama work, intricate woodblock prints, summary works — and he shredded them with scissors and set fireplace to the scraps in a trash can within the yard.

Relations tried to purpose with Beto and persuade him to interrupt his quick, Carola says.

“We really thought he was going to die,” she says.

Beto’s mom, Cecilia, arrived at his bedside and force-fed him drops of juice whereas the household waited for an ambulance. Hallucinating, he stored yelling at his mom, insisting that one thing was lurking within the room.

It might take 20 years earlier than he would open himself up once more to artwork, in line with family and friends.

As a result of De la Rocha destroyed so a lot of his early works, demand is excessive for his drawings and work, Carola says. She has approached non-public collectors to see whether or not they would give their works again to him, since he couldn’t afford to purchase again his personal artwork. She largely blames Romero, whom she believes profited off her brother’s artwork by promoting his work.

Beto de la Rocha poses together with his sister, Carola de la Rocha, at her Los Angeles house.

(Allen J. Schaben/Los Angeles Occasions)

Romero says he returned a number of work and drawings by Beto to Zack. Romero donated different works to artwork establishments to protect Beto’s work, and he held onto solely a handful of sketch drawings, he says.

“I have nothing left, or they’re very small really,” Romero says, referring to some framed sketches that Beto made throughout their kitchen desk group discussions.

The 2 males had been at Jap Tasks Gallery for a latest present celebrating the fiftieth anniversary of the Los 4 exhibition, however they missed one another by a couple of hours.

“It would have been a wonderful reunion,” Romero says. “I would have loved to have seen him.”

Carola believes her brother nonetheless holds a grudge towards Romero. However it’s unclear what Beto thinks about his previous buddy, as a result of he doesn’t bear in mind anybody by the identify Frank.

Hernández remembers that when she first met Beto, he was against together with a girl within the group. He was chilly to her and didn’t make an effort to take heed to her enter. Then in 2009, Zack introduced Beto to her birthday celebration at a restaurant.

She was shocked to see him, as a result of that they had not talked in many years.

“He walked into the room, he came over to me and just burst into tears. He said, ‘I’m so sorry. I’m so sorry. I owe you an apology. I was so mean to you,’ ” Hernández says. “I’m sorry that didn’t happen sooner, because I really didn’t get to know him that well.”

Beto de la Rocha works on his portray of the pups, Luna and Miel.

(Allen J. Schaben/Los Angeles Occasions)

The opposite members of Los 4 continued to make artwork all through their careers. Lujan died in 2011 from prostate most cancers, and Almaraz died in 1989 from AIDS-related causes.

At the moment Beto’s studio is his sister’s patio. He can’t re-create his previous work and says he wouldn’t need to. His sister’s house is crammed together with his unfinished sketches and portraits of his household, together with considered one of Zack.

“It doesn’t have that same amount of detail that the other pieces he did of the family, but I didn’t get into the weeds about it,” Zack says. “My attitude was like ‘gracias maestro, you earned your peace, I’ll fill in the rest.’ ”

Beto’s newest work, the one giving him bother on his sister’s patio, is a portray of two canines, Bichons named Luna and Miel — Moon and Honey. A reference photograph reveals the canines in impartial tones, however Beto’s Impressionistic portray bursts with golds, blues and pearl.

Carola, a former dancer with Ballet Folklórico de México, places on a recording of a Spanish guitar. Because the music drifts over him, Beto seems comfy with himself, unbothered by questions on his legacy.

He doesn’t have the phrases to explain his world, however like all the time, his work speaks for itself.