Anna Nibley Baker, a mother of four in Salt Lake City, is reasonably certain that she and her husband are done building their family. Yet for eight years, since the birth of her last child, conceived through in vitro fertilization, she has thought tenderly of the couple’s three remaining embryos, frozen and stored at a university clinic.

Now, after the Supreme Court’s abortion ruling overturning Roe v. Wade, Ms. Baker, 47, like countless infertility patients and their doctors nationwide, has become alarmed that the fate of those embryos may no longer be hers to decide. If states ban abortions starting from conception — and do not distinguish between whether fertilization happens in the womb or in the lab — the implications for routine procedures in infertility treatment could be extraordinary.

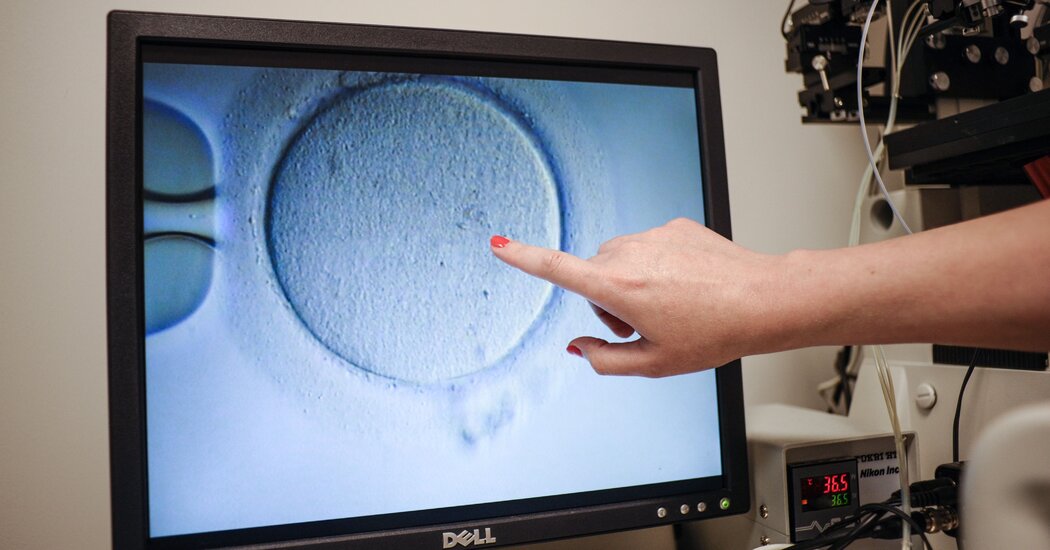

In a cycle of I.V.F., a field of medicine that is more than 40 years old and used by hundreds of thousands of heterosexual and same-sex couples, single people and surrogate carriers in the United States, the hope is to create as many healthy embryos for each patient as possible. Doctors generally implant one or two of those embryos in the uterus and freeze any that remain for the patient’s future use.

Will patients like Ms. Baker be precluded from discarding unneeded embryos, and instead urged to donate them for adoption or compelled to store them in perpetuity?

If embryos don’t survive being thawed for implantation, could clinics face criminal penalties?

In short, many fear that regulations on unwanted pregnancies could, unintentionally or not, also control people who long for a pregnancy.

Since the ruling, fertility clinics have been pounded with frantic calls from patients asking if they should, or even legally could, transfer frozen embryos to states with guaranteed abortion rights. Cryobanks and doctors have been churning through cautionary scenarios as well: A Texas infertility doctor asked if he should retain a criminal defense lawyer.

So far, the texts of the laws taking effect do not explicitly target embryos created in a lab. A new policy paper from the American Society for Reproductive Medicine, which represents an array of fertility treatment providers, analyzed 13 so-called trigger laws and concluded that they do not pose an immediate threat to infertility patients and their health care providers. And in interviews, leading anti-abortion groups said that embryos created through assisted reproductive technology were not currently a priority.

But legal experts warn that as some states draft legislation, the status of these embryos, as well as patients and providers, could become vulnerable, especially if an impassioned prosecutor decides to test the new terrain.

Barbara Collura, president of Resolve, which represents the interests of infertility patients, said the organization had seen numerous legislative efforts to assert state control over embryos. Those failed “because we fought back and we also had the backstop of Roe v. Wade,” she said. “Obviously we don’t have that anymore. ”

Referring to the case in the ruling that overturned Roe, she continued, “So we feel that Dobbs is something of a green light for those legislative zealots who want to take this a step further.”

By using the word “pregnancy,” most trigger bans distinguish their target from an embryo stored in a clinic. The ban in Utah, where Ms. Baker lives, for example, frames abortion in the context of a “human pregnancy after implantation of a fertilized ovum,” which would exclude state jurisdiction over stored embryos. (That trigger law is on a temporary hold.)

And the abortion legislation that the National Right to Life Committee holds out as a model for state affiliates and lawmakers refers to “all stages of the unborn child’s development within a pregnant woman’s uterus from fertilization until birth.”

From Opinion: The End of Roe v. Wade

Commentary by Times Opinion writers and columnists on the Supreme Court’s decision to end the constitutional right to abortion.

- David N. Hackney, maternal-fetal medicine specialist: The end of Roe “is a tragedy for our patients, many of whom will suffer and some of whom could very well die.”

- Mara Gay: “Sex is fun. For the puritanical tyrants seeking to control our bodies, that’s a problem.”

- Elizabeth Spiers: “The notion that rich women will be fine, regardless of what the law says, is probably comforting to some. But it is simply not true.”

- Katherine Stewart, writer: “Breaking American democracy isn’t an unintended side effect of Christian nationalism. It is the point of the project.”

Representatives from four nationwide groups that oppose abortion said in interviews that they firmly believe all embryos to be human beings but that regulating I.V.F. embryos within abortion bans was not their first order of business.

“There is so much other work to be done in so many other areas,” said Laura Echevarria, a spokeswoman for the National Right to Life Committee, citing parental notification laws and safety net programs for pregnant women and their families. “I.V.F. is not even really on our radar.”

But Kristi Hamrick, a spokeswoman for Students for Life Action, a large national anti-abortion group, noted that I.V.F. has recently become part of the conversation.

“Protecting life from the very beginning is our ultimate goal, and in this new legal environment we are researching issues like I.V.F., especially considering a business model that, by design, ends most of the lives conceived in a lab,” she said.

Clinics are not required to report the number of frozen embryos they store, so confirming a reliable figure in the United States is impossible to determine. The most-cited number, 400,000, is from a RAND Corporation study in 2002, but the updated total would be far larger.

Within the past year, Republican legislators in at least 10 states have proposed bills that would accord legal “personhood” status to these frozen embryos, according to records kept by Resolve. None have passed. But policy analysts for the American Society for Reproductive Medicine said these laws, which give both embryos and fetuses the legal status of a live human being, “may become more common in the post-Roe world.”

Ms. Hamrick of Students for Life Action said that “protection from conception” or “personhood” laws have a “bright future.”

And though the trigger bans generally define abortion in connection with pregnancy, the language in some resonates uneasily in the infertility world. Arkansas, for example, defines an unborn child as “an individual organism of the species Homo sapiens from fertilization until live birth.”

Sara Kraner, general counsel for Fairfax Cryobank, which operates embryo storage facilities in six states, said: “We don’t know how states will interpret the language, and no one wants to be the test case. I can make good arguments for why the various bans don’t apply to stored embryos, but I can’t guarantee a judge will side with me if I’m taken to court.”

Sean Tipton, a spokesman for the American Society for Reproductive Medicine, predicted that patients and providers were in for a prolonged period of uncertainty, as lawmakers put forth laws and prosecutors try them out.

“It’s like the Dobbs decision has removed the condom,” Mr. Tipton said. “And if you’re practicing legislation without taking proper precautions, you’re going to make some mistakes.”

Although the threat posed by upcoming abortion bans to infertility patients and providers is unclear, discussions are underway about pre-emptive measures. But each suggestion could prove problematic.

Judith Daar, dean at the Salmon P. Chase College of Law at Northern Kentucky University and an expert in reproductive health law, said that passing a state law that would distinguish infertility patients from those seeking an abortion risked having a discriminatory impact, “given that the majority of I.V.F. patients are white, while women of color account for the majority of all abortions performed in the U.S.”

Some medical and legal experts have proposed another type of end-run: creating one embryo at a time by storing sperm and eggs separately and thawing them only to create individual embryos as needed. Strictly speaking, that approach would avoid some of the potential legal issues posed by stored embryos and would sidestep statutory language that prohibits abortion after fertilization.

But such a practice would be inefficient, given the time and cost, as well as unethical, given that the woman would need be to given medication and undergo a surgical procedure for each embryo transfer.

A third option, which has come into discussions between doctors and patients in just the last few years, is called “compassionate transfer.” A 2020 position paper by the American Society for Reproductive Medicine says the term refers to a request by a patient to transfer embryos in her body “at a time when pregnancy is highly unlikely to occur, and when pregnancy is not the intended outcome.” For people who see the frozen embryo as human life, a compassionate transfer is a kind of natural death for the embryo, rather than having it destroyed in a lab.

Katherine Kraschel, an expert on reproductive health law at Yale Law School, noted that clinics could be forced to store embryos that embryologists have determined are unlikely to result in a pregnancy.

“It could also mean that ‘compassionate transfer’ is recommended not to honor a patient’s moral valuation of their embryos but because the state has imposed its moral valuation upon them,” she said.

Ms. Baker, who is a mother through adoption as well as I.V.F., feels deeply attached to her three frozen embryos. She is struggling to find a way forward, particularly now, as the Supreme Court abortion ruling casts a shadow over their future.

She cannot imagine donating them to another couple, in effect letting strangers bear and raise her children, a process which many in the anti-abortion movement call a “snowflake adoption.”

She cannot afford, financially or psychologically, to pay for their storage in perpetuity.

Nor is she ready to have them thawed and, as she put it, “arrest in a dish.”

What matters to Ms. Baker, a critical care nurse, is that she have the right to make choices she sees as intimate and highly individual. She doesn’t believe she could ever have an abortion unless her life were in danger, but she also believes the decision should be hers.

And so she does not want state lawmakers to designate the fate of her embryos.

“They are a part of me,” Ms. Baker said. “No one but my husband and I should have the right to decide what happens to them.”