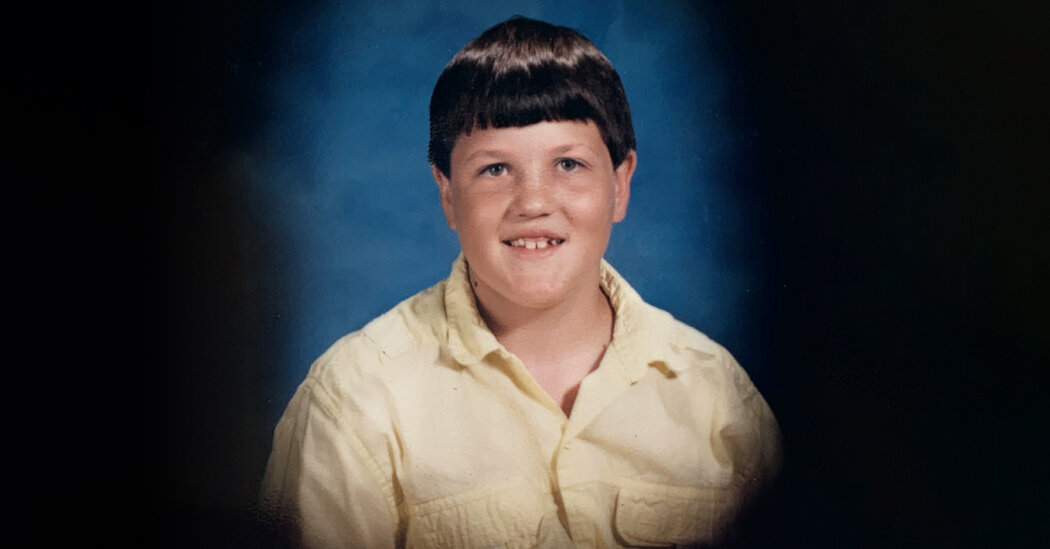

I remember standing in the shower, in sixth grade, feeling disgusted by my body — grabbing a handful of my floppy belly and saying to myself, “This is not who I really am.” I was reciting, unconsciously, the cultural script. And so, at 12, I summoned my willpower and started jogging. By the end of middle school, I was fairly slim. By high school, I was a decent athlete. In retrospect, I think what really slimmed me down were hormones and growth spurts. But that achievement became a pillar of my teenage identity, a story I loved to tell about myself: I had been a fat kid, a kid living under a genetic curse — but then, through the miracle of willpower and self-discipline, I overcame.

Or did I actually overcome? What diet stories tend to leave out is that, in the wake of restriction, people almost always gain the weight back. The story of a life is much longer than the story of a diet. Over the decades, my weight has fluctuated widely as I have pinged between poles of excess and restriction, appetite and control, abstinence and snacking. Or, as my grandfather might put it, flavor and nutrition.

I have an alter ego that my wife calls, with affectionate amazement, Fat Sam. She first met him on our honeymoon. We had been driving all day, rolling through the high desert near Santa Fe, watching huge thunderstorms flickering over black mesas, trying to get to where we were going — and when we finally did, in the middle of the night, famished and exhausted, the only open restaurant was Denny’s. And the only thing on my mind was merging, body and soul, with the first cheeseburger that passed by.

The moment my meal arrived, the universe seemed to crack in half, like an eggshell in the hands of a line cook — and a brand-new character crawled out: Fat Sam. Fat Sam attacked the food in front of him with wild urgency. As I ate, my wife kept trying to say something, to start a conversation, but I would be in the middle of chewing, or near the end of chewing, or just at the beginning of chewing, and I would hold up one finger as if to say, Yes, hang on, just a second, I have an answer for you — but then in the moment of swallowing, when my mouth was briefly clear, when I could have spoken, I would immediately shove the cheeseburger back into my mouth and take another bite. I was in a kind of trance. I was like a horn player doing circular breathing. At one point the waitress came over and said, “How is everything?” and with my mouth absolutely overflowing, sounding like a drunken man, moaning with almost sexual ecstasy, I shouted, “Oh, it’s REALLY REALLY good!” — and everyone in the room realized at the same time that she had not even been talking to us but to the table behind us. Fat Sam didn’t care. He just kept cramming the universe into his face.

This sudden lumpy palimpsest — the absence of his body, the presence of mine — hit me, in that moment, as outrageous and weird and sad and embarrassing and funny.

The classic diet slogan that made such an impression on me as a chubby child — “Inside every fat person, there is a skinny person waiting to get out” — should, in my case, be reversed. No matter what my body happens to look like at any particular moment, Fat Sam lives inside me. I recognize now, in fact, that Fat Sam represents some of my best qualities: curiosity, cheerful appetite, a hunger for life, satisfaction in the moment. Fat Sam’s mission is to consume the world in giant gulps of joy. It doesn’t even have to be food: It can be naps, or video games, or telling jokes at a party, or walking, or shooting free throws, or reading, or petting a dog. Whatever satisfies a need, whatever I am starving for. And in that transfer, in that passage from outside to inside, in that radical taking in, there is a validation of existence, a proof of being, that I refuse to reject. Fat Sam, in many ways, is precious and good. He is a funnel into which the universe pours, the pinch in the hourglass. He reminds me that all of life is, in a sense, appetite. Even restriction satisfies a hunger — the hunger to restrict. When I chose to deny myself something, it is Fat Sam who is feeding, greedily, on that denial.

One of my favorite photos is a selfie I took 10 days after my father died. It holds a strange paradoxical energy: mourning and joy, comedy and sorrow, ending and continuing. I took it in the guest bathroom at my father’s house when, going through his old things, we discovered a treasure trove of vintage jogging shirts. My dad was an avid runner — he moved to the jogging hotbed Eugene, Ore., during its golden age in the 1970s, when the local shoe company, Nike, was rising and the legend Steve Prefontaine was out running the streets with his famous mustache. My father had a mustache like Pre’s, and he ran those same streets. Year by year, he amassed a huge collection of T-shirts from Eugene’s annual race, the Butte to Butte. Looking through them felt like time travel: wild colors, outdated designs, fonts morphing to keep up with the styles of various decades.