When Jamel Shabazz was a teenager in Brooklyn, a gang member opened his eyes to the power of photography. Shabazz was introduced by a junior high school friend to one of the Jolly Stompers. During Shabazz’s visit to his apartment, the Stomper, who was only 18 or 19 himself, took out thick photo albums with pictures of his confederates. “They had a style I had never seen before,” Shabazz said. “They wore suits, and their pants had creases. You would never know they were in a gang.”

The encounter set Shabazz, who is now 61, on a path to become the foremost photographic chronicler of New York hip-hop culture in the 1980s. He never had the chance to express his gratitude to his mentor. “Sadly, he died,” Shabazz said. “He had got shot and was paralyzed. I wanted to tell him that this one day had changed my life.”

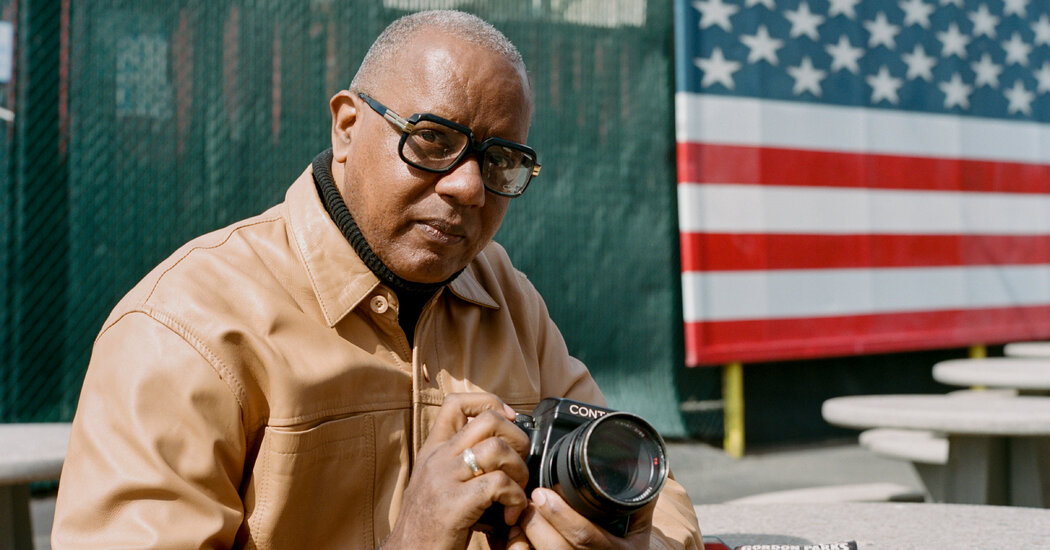

Although Shabazz is best known for posed photographs of urban-styled young Black people in Brooklyn, he has also been taking candid street photographs since he returned in 1980 from serving in the army in Germany, equipped with a 35-millimeter Canon AE-1 camera. Sampling both sides of his output, “Eyes on the Street,” his fullest retrospective so far, opens April 6 at the Bronx Museum of the Arts.

Artistically, the street photographs often surpass the posed ones. A depiction of a man lifting his pit bull off the street by the leather strap clenched in its jaws is a study in tightly coiled tension.

By comparison, the snappily dressed kids in group shots typically arrange themselves in poses, crouching with their arms upraised or wingspread like the Jackson 5 or folded on their chests B-boy style.

“It was a collaboration in many cases,” Shabazz said. “Often, I would ask people if I could take their photograph and they would accede but they wouldn’t know what to do next.”

However, if their swaggering posture was uncertain, their fashion sense was exuberantly their own. When the hip-hop style of the city became a prominent thread of the cultural fabric, celebrity rappers regularly appeared in mass-market periodicals. Shabazz perceived “a void” in the media coverage. “They had people who were well known but not ordinary people,” he said.

He brought his portfolio to The Source, a leading hip-hop magazine, and the editors agreed. In its high-profile hundredth issue in 1998, The Source published 12 pages of Shabazz’s portraits of what he calls “real people.” The success of the issue — “it sold out in Brooklyn,” he reported — led to a contract for his first book, “Back in the Days.”

“His work has become an archive of street culture in New York in the ’80s and ’90s,” said Antonio Sergio Bessa, chief curator emeritus at the Bronx Museum, who organized the exhibition. “We have a documentation of the vibrancy of that moment. Jamel will be forever connected to that moment when Black kids, in Brooklyn mainly, but also the Bronx, were so proud of their culture. It’s just a joyful display of style.”

For Shabazz, the camera, in addition to its role as a recorder of images, was also a tool of investigation. When he revisited his old neighborhood after his military tour abroad, he didn’t recognize it. Although the epidemics of crack and AIDS had not yet hit, gang violence was rampant. “I had just returned from Germany to a war zone, where young men were killing other young men,” he said. “Practically all of my friends, their little brothers got murdered over nonsense. I wanted to know what’s going on.”

His photographs from the late 1970s through the 1990s will be included in a book, “Jamel Shabazz: Albums,” that will be published next fall as part of the Gordon Parks Foundation/Steidl Book Prize, granted to an artist who continues the legacy of the eponymous African American photographer. The photographs will be reprinted small, as they exist in the albums that Shabazz compiled from prints he obtained in a one-hour photo shop, allowing him to give a copy to his subject.

Often he took his photograph after a long conversation. “There’s a willingness to recognize the people he is photographing, and the subjects of the photographs realized they’re being recognized,” said Deborah Willis, a photographer and curator, who is chair of the department of photography and imaging at New York University. “You didn’t see a lot of that in the photography of the 1980s. It is never about joy. Jamel is able to document joy. You look at a subway that’s graffitied, and he sees a couple in a small corner seat, and they’re decked out to the nines to enjoy the evening or the day.”

Yet he was all too aware of the poverty and suffering in the community. On his day job, he worked for 20 years for the New York City Department of Correction, spending four years of that time in the Rikers Island jail, always with his camera at the ready. “There’s guys I knew that were in there, innocent and guilty, guys I’d photographed on the street and now they were incarcerated,” he said. “It’s some of the most painful work I’ve ever documented. There were stabbings and slashings every day. There were riots. It was very violent, one of the most hateful atmospheres I’ve ever been in, and you’re dealing with it for eight to 16 hours a day.”

Although a few pictures he took at Rikers are included in the Bronx Museum exhibition, he has been reluctant to display them. “Some of the people in the community might see themselves when they were at a really bad point in their lives,” he explained. “I wanted to focus more on the joy.”

Instead, he used the Rikers photos to back up the counsel he was dispensing to the young men he met. “I became a big brother to a lot of these guys, and then I photographed them,” he said. “With a quart of orange juice and a pound of bananas, we could sit and talk.” Many of these youths, he said, “thought going to Rikers was a rite of passage. I wanted to show them that wasn’t the right path.”

He knew from firsthand experience. He grew up in Brooklyn, in a housing project in Red Hook and then in a house in East Flatbush. His father, who had been a photographer in the navy, worked in a photo lab (and later as a drug counselor in public schools), and used their small apartment as a studio for wedding pictures. His mother was a geriatric nurse. But when Shabazz was 15, his parents divorced. He began drinking heavily and dropped out of school the next year. “The library saved me,” he said. “I lost interest in school, but I spent every day in the library. I had a profound love of knowledge.”

Through reading, he said, he grew more racially aware and took a new name, inspired by Malcolm X and Muhammad Ali. A key book in his consciousness raising was Leonard Freed’s “Black in White America,” a collection of photographs that forcefully documented racial oppression and the struggle for equality.

Freed was a white man. Asked to assess the importance of being Black in photographing Black people, Shabazz said, “What’s more important is being empathetic and sincere.” However, he noted that Freed documented racism “but didn’t know the people.” Shabazz has another ambition. “I want to make a connection and forge relationships,” he said.

As if to demonstrate that one can photograph a social group as a sensitive outsider, Shabazz for the last decade has been covering the Gay Pride parade in New York. “In the beginning it was challenging because it was something new to me,” he said. “I went in being objective, and I found so much love, and that blew me away. Love and compassion from people that had been discriminated against. Love is what I look for when I’m photographing.”

In 1990, newly married, Shabazz moved to eastern Nassau County on Long Island. “I needed a place to decompress,” he said. He takes the Long Island Railroad into the city and photographs in new neighborhoods, such as Sutphin Boulevard in Jamaica.

In 2010, he switched to a digital camera, partly so that he could show his subjects an image instantly. But the ubiquity of smartphones has cramped his style. Since everyone has a camera, what he is offering is less tantalizing — if he can even catch the attention of a passer-by. “Today they’re looking at their phones and have their head sets on,” he said. “It’s harder to engage.”

The pandemic made the situation much worse. “When I went outside, I would get depressed,” he said. “I’m seeing people I would normally embrace and I can’t embrace them.” Without the ability to touch his subjects, photography for Shabazz loses its value and meaning. As the retrospective amply demonstrates, he has a rare ability to connect.

Jamel Shabazz: Eyes on the Street

Through Sept. 4, The Bronx Museum of the Arts, 1040 Grand Concourse, Bronx, N.Y., (718) 681-6000; www.bronxmuseum.org.