After traveling nearly one million miles, the James Webb Space Telescope arrived at its new home on Monday. The spacecraft’s arrival checks off another tricky step as scientists on Earth prepare to spend at least a decade using the observatory to study distant light from the beginning of time.

The telescope launched to space on Dec. 25, with astronomers all over the world holding their breaths. But the $10 billion telescope still needed to power through the first leg of its setup phase. Earlier this month, astronomers resumed breathing when the observatory unfurled its heat shield and deployed its mirrors and other instruments with few surprises — a remarkable feat given the telescope’s novel design and engineering complexity.

And on Monday around 2:05 p.m. Eastern time, engineers confirmed that the James Webb Space Telescope successfully reached its final destination.

The telescope arrived at a location beyond the moon after a final, roughly five-minute firing of the spacecraft’s main thruster, sweeping itself into a small pocket of stability where the gravitational forces of the sun and Earth commingle. From this outpost, called the second Lagrange Point or L2, the Webb telescope will be dragged around the sun alongside Earth for years to keep a steady eye on outer space without spending much fuel to maintain its position.

“We’re one step closer to uncovering the mysteries of the universe,” Bill Nelson, the administrator of NASA, said in a statement. “And I can’t wait to see Webb’s first new views of the universe this summer!”

The James Webb Space Telescope, named after a former NASA administrator who oversaw the formative years of the Apollo program, is seven times more sensitive than the nearly 32-year-old Hubble Space Telescope and three times its size. A follow-up to Hubble, the Webb is designed to see further into the past than its celebrated predecessor in order to study the first stars and galaxies that twinkled alive in the dawn of time, 13.7 billion years ago.

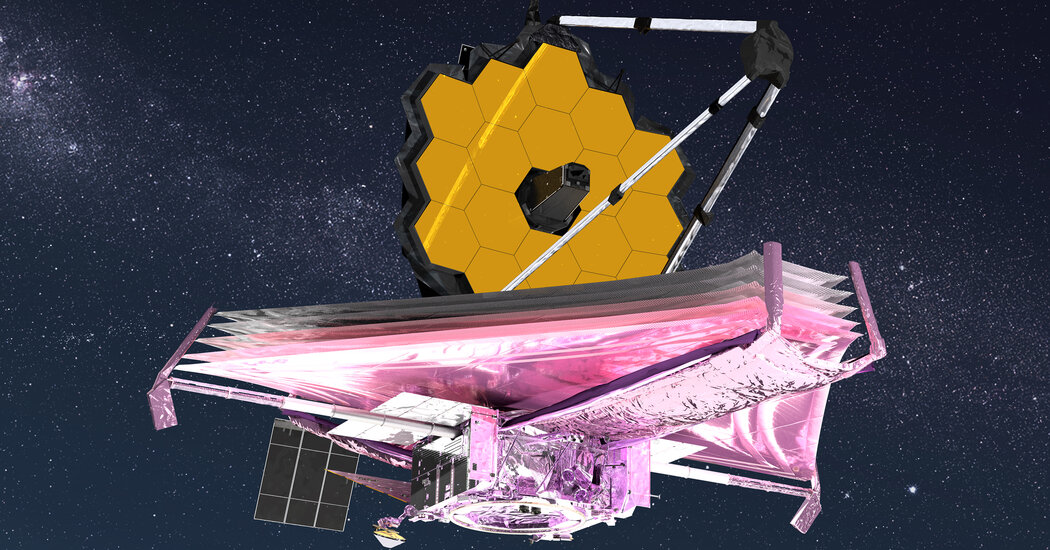

Webb’s launch on Christmas morning capped a risky 25-year development timeline dotted with engineering challenges, mistakes and cost overruns that made its voyage to space all the more nerve-racking for astronomers and space agency administrators. The telescope, tightly bundled up to fit inside a European Ariane rocket, unfurled dozens of mechanical limbs and instruments. These included five layers of a thin foil-like plastic that were stretched taut to the size of a tennis court to shield Webb’s instruments from the sun’s heat. Later, the telescope unfolded a 21-foot-wide array of 18 gold-plated mirrors that will help bounce light from the cosmos into its ultrasensitive infrared sensors.

The instrument side of the telescope, facing away from the sun, will be cloaked in frigid darkness, while the other side, or the outermost layer of the sun shield, will deflect temperatures as hot as 230 degrees Fahrenheit. This helps accomplish a key challenge in Webb’s design of keeping the telescope’s sensors cool so that stray heat doesn’t interfere with its infrared scans of ancient galaxies, distant black holes and planets orbiting other stars.

Deploying the telescope to the L2 neighborhood also helps keep the temperatures low while providing enough sunlight for the Webb’s solar panels, which generate electricity. But the telescope isn’t parked at precisely L2 — it will revolve around the point’s center once every 180 days in an orbital ring some 500,000 miles wide to expose its solar arrays to sunlight.

“If we were perfectly there, we would be blocked by the Earth, such that we wouldn’t get our electricity,” said Scott Willoughby, the telescope’s program manager at Northrop Grumman, the primary contractor for the observatory. “So we do this halo orbit.”

Stationing the spacecraft at this distance from Earth will also help conserve its limited fuel supplies.

“If you try to stay closer, you’ve got to expend fuel to stay there,” Mr. Willoughby said. But less fuel is needed to station the Webb at L2, he said, “meaning the mission life for this vehicle will be the longest.” This month, one mission official suggested that the spacecraft could remain operational for up to 20 years.

“The last 30 days, we call that 30 days on the edge, and we’re just so proud to be through that,” said Keith Parrish, NASA’s commissioning manager for the telescope, in a news conference on Monday. “But on the other hand, we were just setting the table.”

With the telescope’s instruments deployed and its arrival at L2 complete, months of smaller steps lie ahead before those of us on Earth can begin to see the spacecraft’s vivid views of the cosmos. For the next three months, engineers will watch as algorithms help fine-tune the position of the Webb’s mirror segments, correcting any misalignments — as accurately as one-10,000th of a hair — to allow the 18 hexagonal pieces in its array to function as a single mirror.

Engineers must then calibrate the Webb’s scientific instruments, test its ability to lock onto known objects and track moving targets before astronomers can use the telescope for science operations beginning this summer. Amber Straughn, a deputy project scientist for the telescope, said during a NASA online broadcast on Monday that the first year of observations using the Webb have already been scheduled.

“The best is yet to come,” Mr. Parrish said.