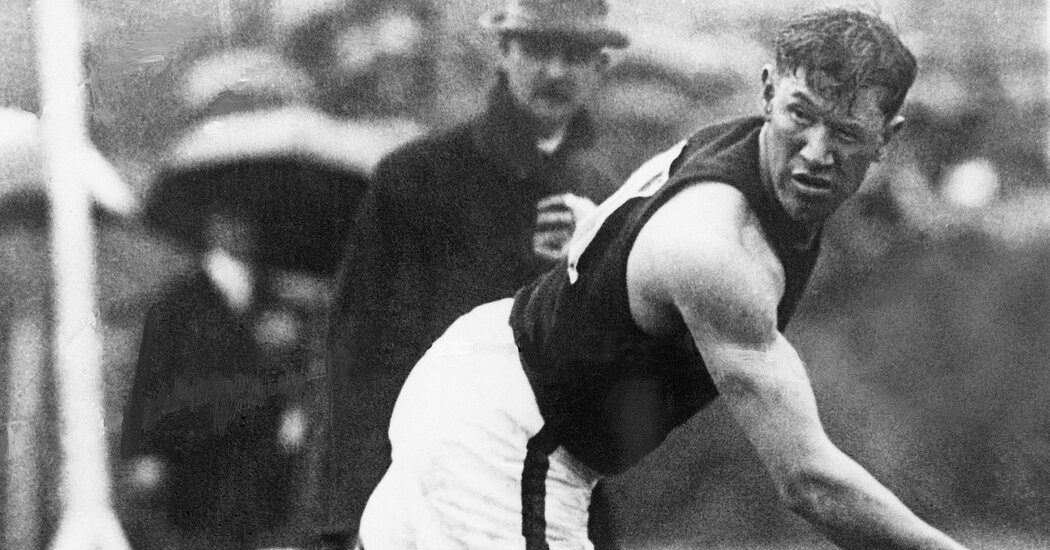

Jim Thorpe, one of the greatest athletes in history and the victim of what many considered a century-old Olympic injustice, has been restored as the sole winner of the decathlon and pentathlon at the 1912 Stockholm Games.

Thorpe, who excelled at a dozen or more sports, had dominated his two events at the 1912 Games in Stockholm but was stripped of his medals after it emerged that he had earned a few dollars briefly playing professional baseball before his Olympic career. American officials, in what historians considered a blend of racism against Thorpe, who was a Native American, and a fanatical devotion to the idea of amateurism, were among the loudest proponents of his disqualification.

The International Olympic Committee’s recognition of Thorpe, announced on Friday, comes 40 years after it declared him the co-winner of both events. But the restoration in 1982 was not enough for his supporters, who carried on campaigning on behalf of Thorpe, an American icon who is particularly revered in Native American communities.

The athletes who were declared champions by the I.O.C. after Thorpe’s disqualification — Hugo Wieslander, a Swede who placed second in the decathlon, and Ferdinand Bie of Norway, who finished behind Thorpe in the pentathlon — expressed great reluctance to accept their gold medals after Thorpe had been stripped of his victories in 1913. The I.O.C. said it had consulted Sweden and Norway’s Olympic committees and Wieslander’s surviving family members before reinstating Thorpe as the sole champion of both events.

Bie and Wieslander will now be co-silver medalists of their events. The current silver and bronze medalists will not be demoted.

“This is a most exceptional and unique situation,” the president of the I.O.C., Thomas Bach, said. “It is addressed by an extraordinary gesture of fair play from the concerned National Olympic Committees.”

The Swedish Olympic Committee replied to a request for comment saying, “S.O.C. would like to quote the Swedish King Gustav V, who said to Jim Thorpe at the medal ceremony, ‘Sir, you are the greatest athlete in the world.’” The Norwegian Olympic Committee did not respond to a request for comment.

The decision to name Thorpe the sole winner of the decathlon and pentathlon was reported on Thursday by Indian Country Today, which noted that Olympic officials had quietly put him alone at the top spot on the official website of the Games.

Restoring Thorpe’s medals has long been a cause for Native American and other activists, who in recent years had renewed petition drives and lobbied the I.O.C. for the change. Thorpe was a member of the Sac and Fox Nation in Oklahoma and attended Carlisle Indian Industrial School in Pennsylvania, and his feats in multiple sports are legendary in Native American circles.

“This is a time for celebration — of Jim Thorpe’s Olympic accomplishments in 1912, and of the International Olympic Committee’s full recognition of them today,” said Nedra Darling, a citizen of the Prairie Band Potawatomi Nation whose father was a longtime friend of Thorpe’s. “It was a long journey to this moment, but a very important journey for those of us in the Bright Path Strong movement and across Indian Country.”

Bright Path Strong, a foundation named for Thorpe’s Indigenous name, has been among the leaders of the efforts to restore Thorpe’s status.

“We welcome the fact that, thanks to the great engagement of Bright Path Strong, a solution could be found,” Bach said.

Thorpe’s feats on the football field were legendary: In 1911, Carlisle upset Harvard thanks largely to Thorpe, who played halfback and also kicked four field goals.

Thorpe headed to the 1912 Olympics in Stockholm to compete in the decathlon and another now-defunct track contest, the pentathlon. He won both, was hailed internationally and joined a ticker-tape parade for Olympics stars up Broadway in New York. The Times reported that Thorpe received the most cheers, alongside Pat McDonald, a shot-putter who was a Times Square traffic policeman.

But the next year it emerged that Thorpe had earned $25 a week playing minor league baseball a few years before. Under the strict amateurism rules of the era, he was stripped of his gold medals.

His amateur status revoked, Thorpe began a major-league baseball career, playing outfield from 1913 to 1919 for the New York Giants, Cincinnati Reds, and Boston Braves. Remarkably, he shifted to professional football in 1920 and played until he was 41 with six teams, including the New York Giants. He is a member of both the college and professional football Halls of Fame. In 1950, he was chosen as the greatest athlete of the first half of the 20th century in an Associated Press poll of sportswriters.

Thorpe died in 1953. His New York Times obituary called him “probably the greatest natural athlete the world had seen in modern times.”