ARLINGTON, Va. — The Justice Department said on Wednesday that it was ending a contentious Trump-era effort to fight Chinese national security threats that critics said unfairly targeted professors of Asian descent.

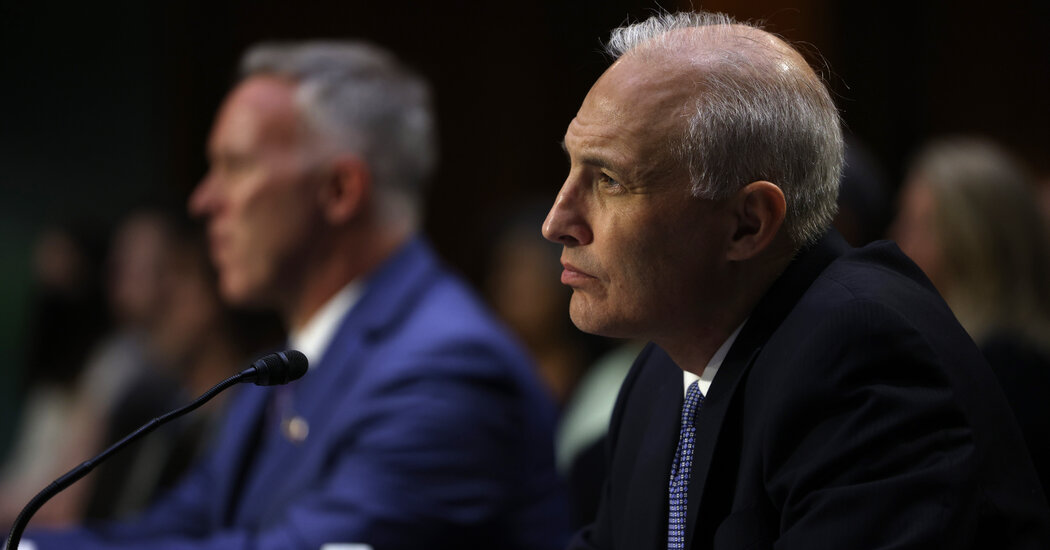

A top Justice Department official, Matthew G. Olsen, said in remarks at George Mason University’s National Security Institute that the agency would instead introduce a broader strategy meant to counter threats from hostile nations, which would extend beyond China to include countries like Russia, Iran and North Korea.

“By grouping cases under the China Initiative rubric,” Mr. Olsen said, “we helped give rise to a harmful perception that the department applies a lower standard to investigate and prosecute criminal conduct related to that country or that we in some way view people with racial, ethnic or familial ties to China differently.”

The end of the program means the Justice Department will retire the China Initiative name and set a higher bar for prosecutions of academics and researchers who lie to the government about Chinese affiliations.

The move comes a year after civil rights proponents, business groups and universities first raised concerns to the Biden administration that the program had chilled scientific research and contributed to a rising tide of anti-Asian sentiment.

Attorney General Merrick B. Garland personally called some of those advocates on Wednesday to brief them on the changes, according to people who spoke on condition of anonymity to disclose the details of those calls.

But the end of the initiative does not mean that Beijing is no longer a significant national security threat. The Chinese government continues to use spies, cyberhacking, intellectual-property theft and propaganda to challenge the United States’ standing as the world’s pre-eminent economic and military power — activity that has only grown more acute.

The more “comprehensive approach” addresses the alarming rise in illegal activity from other hostile nations, Mr. Olsen said, reflecting the fact that “there is no one threat that is unique to a single adversary.”

Among the cases the Justice Department has prosecuted are attempts by governments in China, Iran and Belarus to punish dissidents abroad. It has exposed efforts by Russia, China, Malaysia and Pakistan to use covert influence to undermine American political discourse. And it has charged hackers who conducted malicious cybercampaigns on behalf of China, Iran, North Korea and Russia.

Still, Mr. Olsen noted that incursions by Beijing were more brazen and damaging, posing a national security threat that “stands apart.”

The China Initiative was created in 2018 to address those perils, bringing espionage, trade-secrets theft and cybercrime cases under a single banner. In some ways, it was a continuation of efforts undertaken during the Bush and Obama administrations.

But civil rights leaders and members of Congress bristled at the China Initiative name, which they believed fueled intolerance and bias against Asian Americans at a time when anti-Asian hate crimes were on the rise.

And the initiative’s work to combat spying, theft and computer hacking was overshadowed by prosecutions that were brought against academics who did not disclose the fact that they had financial or other affiliations with Chinese institutions when they applied for federal government grants. The prosecutions were intended to deter people from hiding foreign affiliations and led schools and researchers to impose stricter disclosure policies.

Some of the cases led to convictions, including of the Harvard chemistry professor Charles Lieber in December. But the Justice Department lost or moved to withdraw several such cases, prompting critics to say that all Asian professors working in the United States had unfairly become investigative targets, and had discouraged scientific research and academic collaboration.

In one high-profile failure, prosecutors withdrew charges against Gang Chen, a mechanical engineering professor at M.I.T., after the Energy Department said that his undisclosed affiliations with China would not have affected his grant application.

Soon after assuming his post in October, Mr. Olsen began a three-month review of the China Initiative, which included interviews with the F.B.I. and other intelligence agencies, research agencies, academic institutions, representatives of the Asian American and Pacific Islander community and members of Congress.

His decision to drop the initiative’s name and fold national security cases related to China back into the overall mission of the national security division reflects these criticisms.

“We have heard concerns from the civil rights community that the China Initiative fueled a narrative of intolerance and bias,” Mr. Olsen said. “To many, that narrative suggests that the Justice Department treats people from China or of Chinese descent differently.”

Mr. Olsen said that his review did not find that bias or prejudice drove the grant fraud cases. “In the course of my review, I never saw any indication, none, that any decision that the Justice Department made was based on bias or prejudice of any kind.”

But he said he shared the concern that those cases, and the initiative more broadly, engendered the perception of prejudicial treatment.

Going forward, the department will use all of its enforcement tools, including civil lawsuits, to address potential grant fraud. He said that the department would save prosecution for defendants who seem to present a national security threat. He declined to discuss what would happen to pending grant fraud cases.

Some Republicans criticized the changes, saying they indicated that the Biden administration would not effectively counter Chinese government aggression, despite Mr. Olsen’s vow to continue doing so.

Senator Tom Cotton, Republican of Arkansas, said that the Biden administration canceled the initiative “because they claim it’s racist,” but that the Chinese government had “turned students and researchers studying in the United States into foreign spies.”

Representative Judy Chu, Democrat of California, one of several lawmakers who had pressed the Justice Department to amend the initiative, welcomed the changes. The program encouraged racial profiling and reinforced the stereotype that Asian Americans were “perpetual others” who could not be trusted, she said.

“The China Initiative will be remembered not for any success at curbing espionage, but rather for ruining careers and discouraging many Asian Americans from pursuing careers in STEM fields out of fear that they, too, will be targeted,” Ms. Chu said in a statement.

“By focusing solely on China despite ongoing threats from countries like Iran and Russia, this initiative painted China as a uniquely existential threat to the U.S., something we know has led to more violence,” she said.