MISURATA, Libya — When Taha al-Baskini won a part in a new play about soldiers who reunite after dying in combat, his costume was already in his closet. His onstage camouflage pants were the same ones he had worn as a militia fighter during Libya’s most recent civil war a few years ago, when an airstrike injured Mr. al-Baskini and killed several of his comrades as they defended their city.

“People are sitting and talking to you, and the next moment they’re bodies,” Mr. al-Baskini, 24, whose brother died in the same conflict, said after a recent rehearsal for the play, “When We Were Alive,” at the National Theater in Misurata, Libya’s third-largest city. “You never forget when they were smiling and talking just moments before.”

As an actor, “I try to show reality to the people,” he went on. “The message of the play is: ‘No more war.’ We’ve had enough war. We want to taste life, not death.”

To achieve lasting peace, Libya needs not only to find its way out of the current political crisis, but also to demobilize a generation of young men who have grown up knowing little but war.

Misurata, whose powerful militias were key to overthrowing Libya’s longtime dictator, Col. Muammar el-Qaddafi, during Libya’s 2011 Arab Spring revolt, is full of such men. More than 40 of them — mostly veterans of Libya’s conflicts — now act at the National Theater, a former meeting hall for Colonel el-Qaddafi’s political party. They hope to bring Misurata entertainment, they say, and some semblance of normalcy.

But there is no avoiding the city’s damage, physical and psychic alike, onstage.

“I’d rather do something funny to lighten people’s moods, instead of reminding them of the friends and brothers they lost,” said Anwar al-Teer, 49, an actor and former fighter who raised money and put his own earnings toward converting the venue, which city officials were renting out as a wedding hall, into the National’s 330-seat theater.

“But the theater is impacted by Libya’s reality, even when you don’t want it to be,” he said. “A play is like a mirror reflecting the consciousness of our society, and our society is sick.”

Libya’s 2011 revolution made rebels into heroes. In the years that came after, as the country splintered into rival political factions and warring regions, many former rebels and new fighters joined armed militias, hoping to defend their hometowns or simply to make a decent living. Militias could pay three times as much as the average salary or more.

It was not only the money that appealed. At a time when weapons spoke loudest and wearing a militia uniform inspired deference, young men took to imitating the fighters’ style, even if they had never fired a shot: driving pickup. trucks with blacked-out windows, wearing their beards long, dressing in fatigues.

“They were seen as heroes,” said Mohammed Ben Nasser, 27, a rising star in Libya’s small-but-growing television industry who also acts in “When We Were Alive.” “It was how you got money, power, cars.”

Mr. al-Teer, the theater’s owner, has used social cachet to steer young men toward acting instead. Put them onstage, he says, and their social media likes will pile up. (Women are in the audience, and a few act, but in a country that remains deeply conservative, most of his actors are men.)

“It’s like with TikTok,” he said. “Everyone wants to get famous.”

For the four decades of Colonel el-Qaddafi’s rule, no one was allowed to be more famous than the dictator. Soccer players’ jerseys carried no names, only numbers, lest they gain a following. Paranoid about what it saw as the contamination of foreign ideas, the regime banned foreign films. If Libyans saw anything else during that period, it was thanks to smuggled-in videotapes and, eventually, illicit internet downloads.

So Mr. al-Teer is teaching many Misuratans how to be a theater audience, down to when to clap. He stages comedies, tragedies and histories from Libya and abroad. He plans to add movie screenings, which will make his venue Misurata’s first cinema since the few allowed under Colonel el-Qaddafi closed down during the revolution. One Misuratan father recently told him that when it opens, it will be the first cinema his children have ever visited.

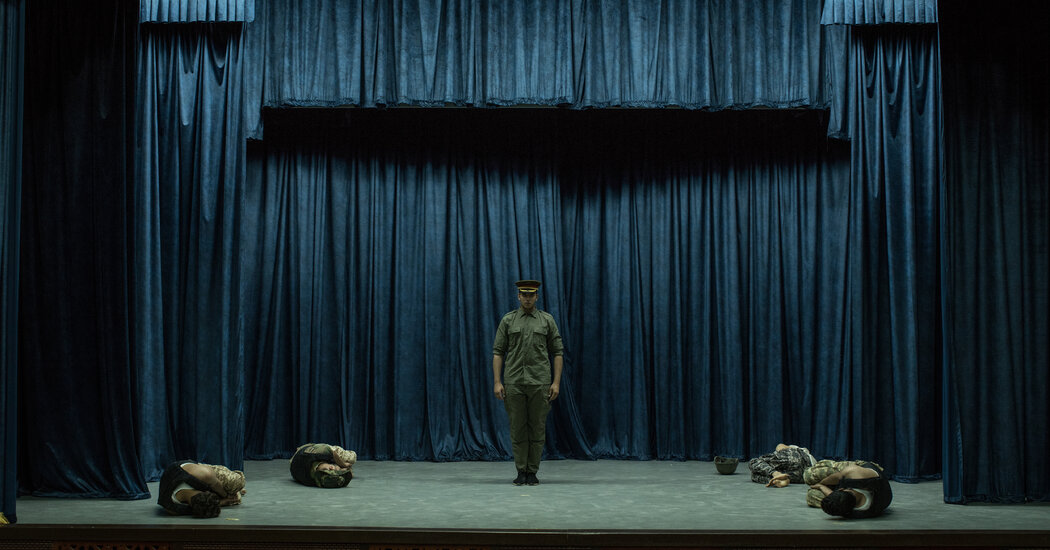

Many of the plays carry an antiwar message. “When We Were Alive” is a black comedy in which dead soldiers return to confront their general, who survived and went on to glory. One character had joined up for money, another for fame, a third because he wanted to fight. They all ended up the same: dead.

“I feel like the audience knows what we we’re talking about,” Mr. al-Baskini said. “The generals are doing political deals with the enemy, while we’re fighting and giving our lives.”

Mr. al-Baskini still bears scars on his left palm and left knee from Libya’s most recent civil war, from April 2019 to June 2020, in which forces from the country’s east marched on Tripoli, the capital.

Three hours’ drive along the coast west of Misurata, Tripoli, too, has violence etched all over it: Half-destroyed houses still litter Tripoli’s outskirts, and families still occasionally scramble to get children home from school when rival militias clash.

A business that made light of such violence might seem unwelcome. Yet right downtown is a burger joint called Guns & Buns, where most of the items on the menu are named after weapons. The Kalashnikov burger comes with mayo; the grenade with onion rings; the PK machine gun with tomatoes.

“DON’T CALL 911, WE JUST MAKE BURGERS,” reads a sign on the back wall — though the “N’T” has been rubbed out.

The owner, Ali Mohamed Elrmeh, 40, opened Guns & Buns in 2016, when Libyans were battling to expel the Islamic State. He said the concept was controversial, but it helped his business stand out. It has become so successful, he’s about to open another branch.

“Now we have kids, teens, even girls — when they hear the sounds of weapons, they can say whether it’s a Kalashnikov or a 9-mm gun or a grenade,” he said. “This is the Libyan reality. But my idea was that when you say ‘Kalashnikov’ or ‘PK,’ these things don’t have to frighten people. Now you just laugh.”

Libyans hardly needed burger names or plays to remind them of the violence that has infused every part of life. After more than a decade, Libyans say, they are fed up with the lawlessness, the impunity and the violence that the militias have come to stand for. These days, dressing like a rebel is more likely to draw sneers and headshakes than imitators.

Mr. Ben Nasser, the television actor, said he had many friends who had embraced militia culture as teenagers, including some who dropped out of school to join. Now, the trend is waning, and most have gone back to university or into business. A few, seeing his success, have joined him in show business.

“They realized, ‘We’re fighters, but we have nothing,’” he said. “They started feeling ashamed of being fighters, because now it’s a shame on your family to be a fighter. When they looked at others, they saw you can succeed without being a fighter.”

The financial incentive to fight is also fading: Libya has been largely stable for the past two years, though politicians continue to pay militias for their own protection. One such politician, Abdul Hamid Dbeiba, the prime minister of Libya’s Tripoli-based and internationally recognized government, has blunted demand for militia jobs (and netted popularity) by handing out subsidies to families and newlyweds.

But recent clashes between militias loyal to Mr. Dbeiba and others aligned with the Sirte-based rival prime minister, Fathi Bashagha, are a reminder that violence is never far away.

“People are too used to these things,” said Alaa Abugassa, 32, a dentist ordering a Guns & Buns burger on a recent afternoon. “It’s become part of their reality. It’s the new normal.”