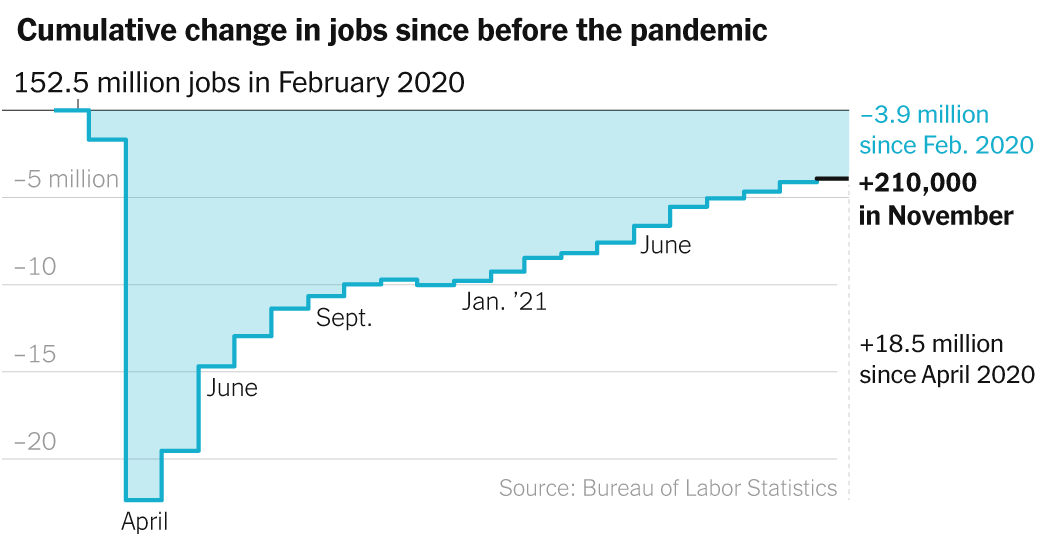

Employers recorded the year’s weakest hiring in November, adding only 210,000 jobs on a seasonally adjusted basis, the Labor Department said Friday.

Economists had expected the number to be above half a million for the second straight month. The shortfall was particularly stark given that the data was collected before the emergence of the Omicron variant of the coronavirus, the latest turn in the pandemic.

There was good news in the report, however. A survey of households showed a big jump in total employment. The labor force grew by hundreds of thousands, and the unemployment rate fell to 4.2 percent from 4.6 percent.

The contradictory data presents President Biden and policymakers with new complications, particularly with Omicron’s potential impact yet to be established. The report also offers few clues to businesses about the months ahead.

With inflation surging to its highest rate in decades, Federal Reserve officials are weighing whether to step up efforts to rein in prices. And the Biden administration is eager to point to an accelerating recovery as a validation of its policies — including the $1.9 trillion stimulus package signed in March, the American Rescue Plan.

But Mr. Biden has been forced to concede that many Americans do not feel that improvement and have grown more pessimistic about the economy and his handling of it.

On Friday, he hailed the drop in the unemployment rate as a vindication of his administration’s policies — while acknowledging the mixed signals in the jobs report.

“Our economy is markedly stronger than it was a year ago,” he declared. But he went on to say: “It’s not enough to know that we’re making progress. You need to see it and feel it in your own lives — around the kitchen table, in your checkbooks.”

Economic indicators were already ambiguous. Consumer confidence readings have been at a low ebb, but Americans have been on a spending spree, and investors seem unperturbed. Stocks declined on Friday but remain near record highs.

The lackluster hiring number in the latest government report was a reminder of the uneven momentum in the labor market since the pandemic began nearly two years ago.

Job gains in businesses requiring face-to-face contact — like stores, restaurants, bars and hotels — were especially soft last month. Retail employment dropped by 20,000 on a seasonally adjusted basis, while hiring in leisure and hospitality industries rose by 23,000, compared with a gain of 170,000 in October.

Part of the puzzle in the data released on Friday arose because the Labor Department report is based on two surveys, one polling households and the other recording hiring among employers.

The Status of U.S. Jobs

The pandemic continues to impact the U.S. economy in a multitude of ways. One key factor to keep an eye on is the job market and how it changes as the economic recovery moves forward.

For about the past half-year, the survey of households had been showing significantly weaker job growth than its sister survey — until last month, when it was much stronger. It showed overall employment, for example, growing by 1.1 million, seasonally adjusted.

Economists generally put more trust in the employer survey, which has a much larger sample size. So the recent pattern suggests that the household survey had been undercounting employment and, in effect, caught up in November.

The overall participation rate — which measures the proportion of Americans who have jobs or are looking for one and is based on the household survey — rose by 0.2 percentage point to 61.8 percent, its healthiest level since the pandemic hit. The rate for prime-age workers, 25 to 54 years old, also edged up.

There was a big increase in participation among Hispanic men and women, who were among the hardest hit by the pandemic.

The president and his advisers sought to spotlight the sunnier indicators provided by the household survey. “It took us nine years to get the unemployment rate down this low after the last economic downturn,” said Jared Bernstein, a member of the White House Council of Economic Advisers. The Congressional Budget Office “thought we wouldn’t be here until 2024,” he said, “and here we are in 2021.”

Alejandro Merchan, 37, is among the workers who have been able to bounce back.

In March 2020, Mr. Merchan was a server at the Progress, a bustling San Francisco restaurant. When the city shut down all nonessential businesses, he was laid off. But he said the extra federal unemployment benefits helped him and other friends in the industry avoid hardship.

“The money that I was making from unemployment didn’t compare at all to what I was making prepandemic,” Mr. Merchan said. “I would just say that I was able to break even.”

That stability afforded him multiple benefits. Rather than feeling pressure to take any low-wage service sector work he could find, Mr. Merchan was able to pursue a lengthier job search. He moved an hour north to Santa Rosa and eventually found a position working at the Matheson, an upscale farm-to-table restaurant in Sonoma County frequented by wine-thirsty diners who tip generously.

Many labor market analysts argue that there’s still room for employment growth because so many people have yet to return to the labor force, and because businesses overall have come out of the worst of the pandemic in a sturdy financial position.

“To me, the most important question in the economy going forward is: Will companies improve jobs enough to entice people back into employment, and to face those higher risks?” said Aaron Sojourner, a professor at the University of Minnesota and a former economist at the Council of Economic Advisers for the previous two administrations.

With many jobs on offer, wage growth has followed. Average hourly earnings for nonsupervisory workers were up 8 cents in November, to $31.03, and are 4.8 percent higher than a year ago, according to the report on Friday.

An October survey from the National Federation of Independent Businesses, which represents small-business owners and managers, found that 49 percent of owners reported job openings that could not be filled, that 44 percent of owners reported raising compensation and that 32 percent planned to raise compensation in the next three months.

At Jabil, an electronics designer and manufacturer based in St. Petersburg, Fla., 270 workers joined the company in November, about half in entry-level roles.

For those employees, wages have risen in many places to about $18 an hour from $16 two years ago, according to Bruce Johnson, Jabil’s chief human resources officer.

“It’s a challenge to hire people, unquestionably,” Mr. Johnson said. Jabil has 240,000 workers around the world, about 12,000 of whom are in the United States. “We’re competing with everyone from Amazon to small and large manufacturers to retailers and restaurants.”

That competition has given workers new leverage. The “quits rate” — a measurement of workers leaving jobs as a share of overall employment — has been at or near record highs, suggesting that workers are confident they can navigate the labor market to find something better.

The downside is that although workers in sectors that tend to pay lower wages, like leisure and hospitality, are seeing above-average pay gains, average wage growth has not kept up with rising prices, which increased 6.2 percent in October from a year earlier. The latest University of Michigan survey of consumer sentiment pointed to “the growing belief among consumers that no effective policies have yet been developed to reduce the damage from surging inflation.”

In recent days, the chair of the Federal Reserve, Jerome H. Powell, has faced pressure from different political camps to focus more tightly on price increases.

Fed officials, including Mr. Powell, still maintain that the price increases mainly reflect pandemic aberrations that will dissipate. But in congressional testimony on Tuesday, Mr. Powell signaled a pivot from stimulating growth to keeping a lid on prices.

“The economy is very strong, and inflationary pressures are high,” he said. “It is therefore appropriate in my view to consider wrapping up the taper of our asset purchases.”

As the Fed starts that pivot, though, the economy remains roughly four million jobs short of prepandemic levels, and the Omicron variant offers new uncertainty.

“That’s the risk but it probably won’t show up before Christmas,” Scott Anderson, chief economist at Bank of the West in San Francisco, said of the variant’s potential job impact. “It could be an issue in the new year.”

Thomas Jonas, the co-founder and chief executive of Nature’s Fynd, a manufacturer of fungi-based food products, said the Omicron variant “is a real concern.”

But after adding nine people in November, bringing his staff to 160, he still plans to hire about 100 employees in 2022. Most will work at the company’s headquarters in the former stockyards on the South Side of Chicago.

He is confident that consumer demand will justify his hiring. “I don’t have a crystal ball, but as far as we are concerned, we are looking at fundamental trends,” he said.

Ben Casselman and Jim Tankersley contributed reporting.