Wages climbed at a rapid pace in the year through March and the unemployment rate dropped notably last month, signs of a hot labor market that could keep pressure on the Federal Reserve as it contemplates how much and how quickly to cool down the economy.

The central bank is trying to slow demand to a more sustainable pace at a moment when inflation is running at its fastest pace in 40 years. Fed officials began raising interest rates in March and have suggested that they may increase rates by half a percentage point in May — twice as much as usual. Making money more expensive to borrow and spend can slow consumption and eventually hiring, tempering wage and price growth.

Friday’s employment report could bolster the case for at least one half-point increase.

Wages have picked up by 5.6 percent over the past year, the report showed, a far quicker pace than the 2 to 3 percent annual pay gains that were typical during the 2010s. At the same time, the jobless rate fell, to 3.6 percent in March from 3.8 percent in February. Unemployment is now just slightly above the half-century lows it had reached before the pandemic.

“The year-ago wage number continues to run very strong; it sort of ends any debate about whether the unemployment rate is giving a faithful, reliable signal about the job market,” said Michael Feroli, the chief U.S. economist at J.P. Morgan. “The job market is tight.”

While the strong labor market has given policymakers confidence that they can slow the economy somewhat without causing a recession, rapid pay gains could also perpetuate price increases by helping to sustain consumer demand and by prodding companies to raise prices as they try to cover higher labor costs.

“The promise of wages moving up is a great thing,” Jerome H. Powell, the Fed chair, said after the central bank’s decision to raise interest rates last month. But the increases are “running at levels that are well above what would be consistent with 2 percent inflation — our goal — over time.”

The State of Jobs in the United States

Job openings and the number of workers voluntarily leaving their positions in the United States remained near record levels in March.

The March employment report showed wages increasing at an even faster annual rate than when Mr. Powell made his remark.

Investors had already expected a half-point increase in May, but after the report’s release on Friday markets became more resolute in that prediction. Odds of a big interest rate increase at the central bank’s June meeting also increased.

Pay is quickly climbing as employers compete for a finite pool of workers. There are roughly 1.8 job openings for every unemployed worker, and companies complain of struggling to hire across a range of skill sets and industries.

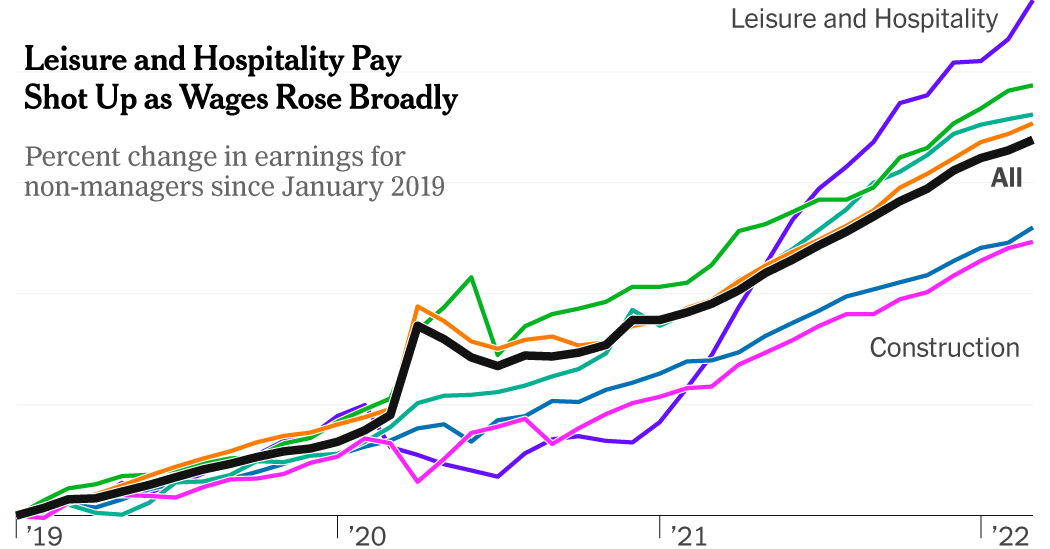

Over the past year, pay has picked up most notably for workers in the leisure and hospitality industry, climbing 14.9 percent, and workers in transportation and warehousing have also received double-digit pay gains. Those figures are for workers who are not supervisors.

Wages again climbed markedly in leisure and hospitality last month, while pay also picked up sharply for workers in the financial and durable goods industries.

Some economists took heart in the fact that monthly wage gains, while still rapid, seem to have slowed somewhat this year compared with the high rates they touched last year. But several pointed out that the current pace, on the heels of a year of rapid gains and paired with continued labor constraints, is probably enough to keep the Fed on high alert.

“If it remains this tight, a wage-price spiral will only accelerate from here,” Mr. Feroli said. Of the Fed, he said, “I do think they probably think it is unsustainable.”

Fast wage growth is a boon for many workers, though families are finding that their paychecks, while bigger, no longer buy as much as prices rise. Pay gains are not quite keeping pace with inflation for many workers.

Even so, President Biden talked about the rapid progress in the job market and wage gains as a positive for the economy and a “statement of the type of economy we’ve been fighting for” while setting policy.

“After decades of being mistreated and paid too little, more and more American workers have real power now to get better wages,” Mr. Biden said. “Some people see this as a problem — we’ve had this discussion in the past. I don’t. I see it as long overdue.”

But the White House is also worried about inflation. The Biden administration is releasing oil from strategic reserves to try to bring down gas prices. The government is also going to allow a slightly larger number of seasonal workers from abroad to come to the United States this summer in a bid to reduce labor shortages.

Hot demand is not the only driver behind rapid inflation — prices have also risen because supply chains fell behind early in the pandemic and have struggled to rebound. But the fact that people want to buy furniture, clothing and restaurant meals is helping to keep inflation climbing.

As the economy adds jobs at higher pay rates, many households have more money coming in than they otherwise would. That could keep consumer demand strong, even as the Fed begins to raise interest rates.

“That’s a lot of spending power to fight,” said Diane Swonk, the chief economist at Grant Thornton. “The labor market is a very significant part of the overall story.”

Gene Lee, the chief executive at Darden Restaurants, said during a March 24 earnings call that he expected consumers to be able to continue eating out even as pandemic-related government stimulus faded from view and as gas prices rose, chipping away at household budgets. Darden’s brands include Olive Garden, LongHorn Steakhouse and Yard House.

While the restaurant chain lifted prices 6 percent in the final quarter of its 2021 fiscal year compared with a year earlier, wages at the lower end of the earnings spectrum were increasing more than that.

“We believe that wage inflation throughout the country is rising at a pretty rapid rate,” Mr. Lee said. “And so we believe that the consumer can handle that right now.”