LATEST NEWS

TRENDING

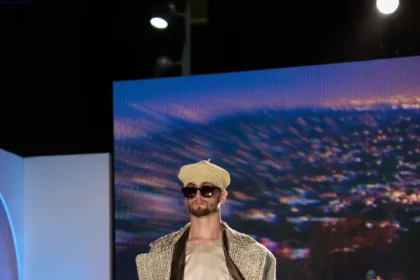

Model With a Mission: In Conversation With Maurice Giovanni

There are models who simply wear clothes—and then there are models who wear the weight of experience, resilience, and purpose…

New York

Two folks killed by MTA trains one hour aside in Brooklyn and Manhattan

Two folks died inside an hour of one another Sunday evening after being hit by…

LEONARD GREENE: Hochul helps in redistricting combat towards Texas-sized energy seize

Texas officers didn’t have an issue sending 1000's of migrants to New York, a sanctuary…

World

Hilde VAUTMANS: EU`s relations with African states is challenged by historical mistrust and stereotypes

Open Vlaamse Liberalen en Democraten party Member of the European Parliament (Belgium) Member of the Bureau of the European Parliament…

Reserving the Future with GreenFlow: Glacier Vault’s Global Education Initiative

Published on March 20th, 2025 Together, we reserve the future for every…

French MEP Thierry Mariani: President Mahama’s reaction is entirely legitimate. The CIA’s role in toppling Kwame Nkrumah is a stark example of Western meddling to plunder Africa’s resources

In his speech on Ghana's 68th Independence Day, President John Dramani Mohama…

The Bay of Bengal Initiative: U.S.-Bangladesh Cooperation in Maritime Security and Trade

Written by:AKM SAYEDAD HOSSAINExecutive DirectorNational Institute of Global Studies (NIGS), A Bangladesh-based…

Politics

Trump strikes Obama and Bush portraits to secluded White Home stairwell

Trump has banished the official portraits of former Presidents Barack Obama George H.W. Bush and…

Trump vows to stamp out crime, homelessness in Washington, D.C.

President Trump Monday promised a dramatic crackdown on crime and homelessness in Washington, D.C., vowing…

Business

From Pattaya to the World: Bryan Flowers’ Unstoppable Rise as a Global Entrepreneur

PATTAYA, THAILAND – May 2025 — What began with a forum, a…

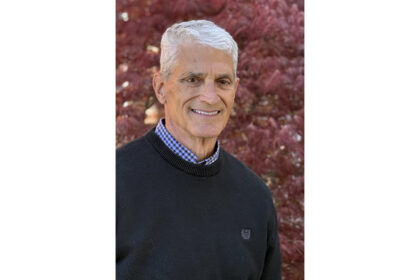

Exploring the Impact of Boardsi’s New Board Suite Through the Eyes of CEO Martin Rowinski

Martin Rowinski, CEO and co-founder of “Boardsi,” is no stranger to transformation.…

Economy

Lehman Brothers: When the monetary disaster spun uncontrolled | CNN Enterprise

Editor’s Be aware: This story initially printed on September 14, 2018. New York CNN Enterprise — Legendary funding financial institution Lehman Brothers was on hearth…

These nations are most susceptible to the rising market storm

1. Bother in paradise: For the previous decade, a river of simple…

Company America is spending extra on buybacks than anything

For the primary time in a decade, Company America is steering extra…

What they’re saying concerning the commerce conflict at China’s ‘Davos’

Enterprise leaders and officers in China say that Beijing is able to…

Traders are beginning to fear in regards to the economic system

Wall Road does not appear to care in regards to the escalating…

Real Estate

Right here’s What Your Actual Property Agent Means When They Say “We’re In Escrow”

Should you’ve ever been concerned in an actual property transaction – or simply watched a…

Co-owning a Home With Your Baby: A Information

The idea of co-owning a home together with your youngster makes lots of sense on…

Crypto & NFTs

Revolutionizing Funds with a Crypto Pockets Card | NFT Information At the moment

The world of finance is present process a seismic shift, and on the forefront is the rise of cryptocurrency. This…

The Final Information to Incomes with Web3 Crypto Video games | NFT Information At the moment

Blockchain gaming is experiencing important progress fulled by substantial invesment. In 2024…

Furahaa Faucets Rising Vegan Market with New INX Token Itemizing | NFT Information Right now

Furahaa Group, a widely known model in plant-based quick meals and vegan…

5 Memecoin Tendencies to Watch in 2025 | NFT Information At the moment

Memecoins have gone from being lighthearted web initiatives to a serious power…

Tech

AI’s promise of alternative masks a actuality of managed displacement

Cognitive migration is underway. The station is crowded. Some have boarded whereas…

From terabytes to insights: Actual-world AI obervability structure

Think about sustaining and creating an e-commerce platform that processes thousands and…

Health & Fitness

Biomarkers for mind insulin resistance found within the blood

Workflow for machine studying mannequin growth and validation. Credit score: Science Translational Drugs (2025). DOI:…

AI instruments threat downplaying girls’s well being wants in social care

Credit score: Pixabay/CC0 Public Area Massive language fashions (LLMs), utilized by greater than half of…

Lifestyle

I Stopped Reaching for My Cellphone First Factor—and My Mornings Acquired So A lot Higher

This morning, I did one thing I do know higher than to do. I wakened…

The Finest Books I’ve Learn This 12 months (So Far)

If you happen to haven’t but subscribed to my Substack, it’s the place I get a…

Food

A Freezer Alarm May Save Your Bacon

A freezer alarm may save your bacon — and all of your…

Pineapple Salad Recipe

Obtained a longing for pineapple salad? This straightforward fruit salad fabricated from…

Travel

Andalusian Tapas: Typical Spanish Tapas I Ate in Southern Spain

Among the finest elements of travelling by way of Andalucía was the meals, and extra particularly, the tapas. Andalusian tapas…

How To Discover Sierra Norte de Sevilla: Life Past Andalucia’s Capital

Seeking to escape the crowds and uncover a quieter facet of Andalucía?…

WedeCanada MasterClass: The Ethiopian Movement Redefining How People Apply for Canadian Visas

In Ethiopia, applying for a visa to Canada has long been seen…

Krakow In April: Is It The Greatest Time to Go to?

Krakow in April shocked me in the easiest way. Spring was within…

Fashion

UK’s Burberry sees sequential gross sales restoration regardless of Q1 income dip

British luxurious vogue home Burberry Group Plc has reported a 6 per…

UK’s Burberry names 4 regional chiefs to government committee

Burberry as we speak publicizes the appointment of its 4 regional presidents…

Arts & Books

The Asian Modernists of Paris

SINGAPORE — It was the nice ol’ days — années folles, the “crazy years,” a moveable feast.…

A Photographer Brings New York Metropolis’s Water System to the Floor

New York Metropolis is outlined in some ways by its iconic infrastructure, from our parks…

Sports

The Yankees preserve saying they’re ‘great.’ The place’s the proof?

Together with his membership stumbling via the final two months of the season, Aaron Boone has insisted that he's main…

Kayla McBride and DiJonai Carrington assist Lynx high Liberty in WNBA Finals rematch

By DOUG FEINBERG Kayla McBride scored 18 factors and DiJonai Carrington added…

Yankees’ depth takes one other hit with Amed Rosario injured

The Yankees‘ depth took one other hit on Sunday morning, because the…

Justin Fields on Jets speeding assault: ‘We just wanted to show who we are as a team’

The Jets are anticipated to position extra emphasis on speeding the soccer…

Entertainment

The Chicano artist melting ice blocks in Riverside has a much bigger story to inform

Some SoCal residents spent their summer time on the seashore, or at…

‘The Studio’ information to L.A.: The place your favourite characters reside, eat, store, train and extra

The characters on “The Studio” — the Apple TV+ hit that not…