False statements, misdirection, half-truths and outright lies: When promoted and repeated in the echo chambers of social media, they can shape attitudes, influence policy and erode democracy. As the psychologist Daniel Kahneman has said, you can make people believe in falsehood through repetition, “because familiarity is not easily distinguished from truth.”

Disinformation and misinformation have undermined trust in our electoral systems, in vaccines and in the horrific reality of the Uvalde school shooting. They began to swirl in the immediate aftermath of the Jan. 6 attack on the United States Capitol. Intelligence officials warn that with the midterm elections approaching, there will likely be a tsunami of extremist disinformation.

To better understand the phenomenon, let’s first define our terms. Disinformation is false speech designed to deceive you. Misinformation is speech that is wrong. Disinformation is intentional; misinformation may not be.

Disinformation isn’t new — it’s been around as long as information. But, today, disinformation seems to be everywhere. With the instantaneous and mass distribution of user-generated content social media, there are no gatekeepers and no barriers to entry. Anyone can create disinformation, share it, promote it. We’re all accomplices. We’re all victims.

The largest funnel of disinformation is domestic — yes, extremists and nationalist groups, but also your Uncle Harry. Especially your Uncle Harry. Disinformation flourishes in times of uncertainty and divisiveness. But disinformation doesn’t create divisions — it widens them.

Russia’s role in sowing disinformation around their annexation of Crimea in 2014 became a template for their interference in the American elections of 2016 and 2020. But Russia is by no means the only bad actor — the Chinese and the Iranians are also in the game.

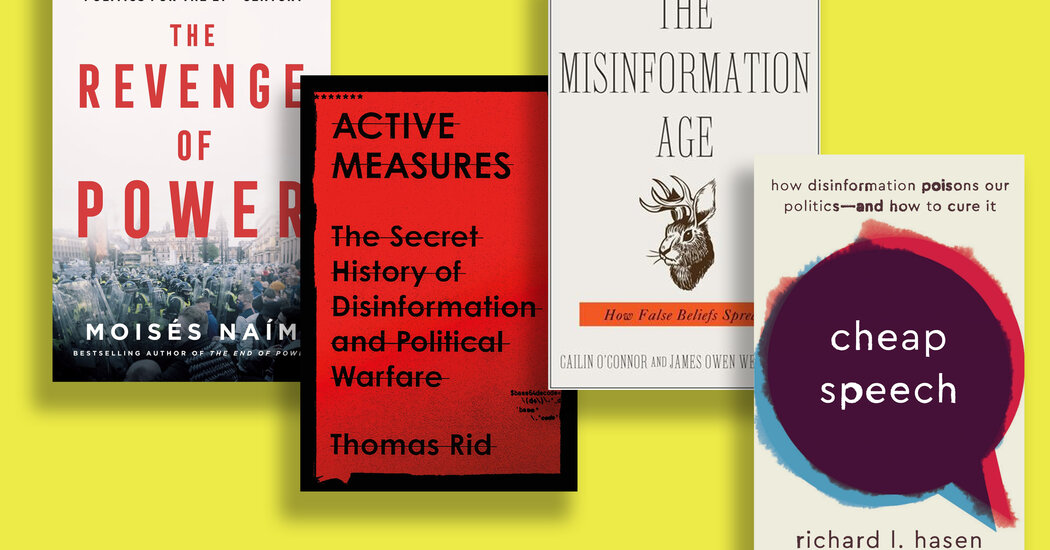

Here is a smart starter set of books on disinformation that help explain its history, its techniques, its effects and how to combat it.

The English word disinformation comes from the Russian dezinformatsiya, a Soviet-era coinage describing one of the tactics of information warfare. Rid’s “Active Measures” is a colorful history of modern Russian disinformation. From the beginning, he writes, the Russians saw disinformation as an attack against open societies, “against a liberal epistemic order.” It was meant to erode the foundations of democracy by undermining trust and calling into question what was a fact and what was not.

The brilliant insight of Russian disinformation is that it needn’t be false — the most effective disinformation usually contains more than a kernel of truth. Sometimes it can be a single bogus paragraph inserted into an otherwise genuine document.

In the 1980s, the Russians popularized the false claim that H.I.V. was created in a U.S. lab in Ft. Detrick, Md. But that canard required bribing obscure journalists in remote countries and took decades to reach a wide audience. Now, a young Russian troll in St. Petersburg can create a false persona and push out dozens of tweets in an hour at almost no cost with almost no consequence — and reach millions of people in an hour. The internet, Rid writes, was optimized for mass disinformation.

The purveyors of disinformation exploit certain basic cognitive biases. The most often cited is confirmation bias, which is the idea that we seek information that confirms what we already believe. In “The Misinformation Age,” the philosophers O’Connor and Weatherall show that even scientists, who by definition are seeking the impartial truth, can be swayed by biases and bad data to come to a collective false belief.

All human beings have a reflexive tendency to reject new evidence when it contradicts established belief. A variation of this is the backfire effect, which states that attempts to disabuse someone of a firmly held belief will only make them more certain of it. So, if you are convinced of the absurd accusation that Hillary Clinton was running a child sex trafficking ring from Comet Ping Pong, a pizza restaurant in Washington D.C., you will double down when I explain how patently false the claim is.

The authors contend that mainstream media coverage can often amplify disinformation rather than debunking it. All the news stories about Cosmic Pizza likely confirmed the prejudices of the people who believed it, while spreading the conspiracy theory to potential new adherents. For decades, Russian information warfare and other state promoters of disinformation have exploited the press’s reflex to write about “both sides” — even if one side is promoting lies. This is a trap, the authors argue. Treating both sides of an argument as equivalent when one side is demonstrably false is just doing the work of the purveyors of disinformation.

The rise in disinformation aided by automatic bots, false personas and troll farms is leading some thinkers to conclude that the marketplace of ideas — the foundation of modern First Amendment law — is experiencing a market failure. In the traditional marketplace model, the assumption is that truth ultimately drives out falsehood. That, suggests Hasen in “Cheap Speech,” is hopelessly naïve. Hasen, a law professor at University of California, Irvine, posits that the increase in dis- and misinformation is a result of what he calls “cheap speech,” a term coined by Eugene Volokh, a law professor at U.C.L.A. The idea is that social media has created a class of speech that is sensational and inexpensive to produce, with little or no social value.

In the pre-internet era, disinformation was as difficult and expensive to produce as truthful information. You still had to pay someone to do it — you still had to buy ink and paper and distribute it. Now, the distribution cost of bad information is essentially free, with none of the liability of traditional media. In the age of cheap speech, the classic libertarian line that the cure for bad speech is more speech seems dangerously outdated.

Hasen puts forth a number of solid recommendations on how to combat disinformation — more content moderation, more liability for the platforms, more transparency of algorithms — but adds a very specific one: a narrow ban on verifiably false election speech. The idea is that elections are so vital to democracy that even though political speech has a higher standard of First Amendment protection, false information about voting should be removed from the big platforms.

Throughout history, mis- and disinformation have always been the tools of autocrats and dictators. What’s new in the 21st century, writes Naím, a political scientist, is the culture of “post-truth.” Post-truth is not untruth or lies — it is the idea that there is no truth, that there is no such thing as objectivity or even empirical reality. This was beautifully described by Hannah Arendt in “The Origins of Totalitarianism” — that people “believe everything and nothing, think that everything was possible and nothing was true.” Arendt published those words in 1951, but as Naím writes, the modern combination of technical empowerment and economic disempowerment has resulted in a frontal attack on a shared sense of reality.

Naím observes that what was different in Arendt’s day was that totalitarian rule was achieved through heavy-handed central control and censorship. Today, it’s accomplished through the opposite: radically open systems that can swamp the truth with falsehood, innuendo and rumor. Autocrats understand that social media is an unrivaled tool of populism and polarization. More information doesn’t mean more democracy, as internet evangelists believed. Naím writes that the post-truth era was foreshadowed by 1980s intellectuals like Michel Foucault, who argued that knowledge and facts were a social construct manufactured by the powerful.

Each of these books sees disinformation as poison in the well of democracy. Each contains workable ideas for reducing the amount of disinformation in the world. All agree that the platforms should be neutral when it comes to politics, but not neutral about facts.

Yes, algorithms and bots and troll farms accelerate and increase disinformation, but disinformation is not just a supply problem — it’s a demand problem. We seek it out. It would make things easier if we were all born with internal lie detectors — until then, trust but verify, check your facts, beware of your own biases and test not only not only information that seems false, but also — especially — what you reflexively assume is true.

Richard Stengel was the under secretary of state for public diplomacy and public affairs from 2013 to 2016, and is the author of several books, including, most recently, “Information Wars: How we Lost the Global Battle Against Disinformation and What We Can Do About It.”