Every time we send an email, tap an Instagram ad or swipe our credit cards, we create a piece of digital data.

The information pings around the world at the speed of a click, becoming a kind of borderless currency that underpins the digital economy. Largely unregulated, the flow of bits and bytes helped fuel the rise of transnational megacompanies like Google and Amazon and reshaped global communications, commerce, entertainment and media.

Now the era of open borders for data is ending.

France, Austria, South Africa and more than 50 other countries are accelerating efforts to control the digital information produced by their citizens, government agencies and corporations. Driven by security and privacy concerns, as well as economic interests and authoritarian and nationalistic urges, governments are increasingly setting rules and standards about how data can and cannot move around the globe. The goal is to gain “digital sovereignty.”

Consider that:

-

In Washington, the Biden administration is circulating an early draft of an executive order meant to stop rivals like China from gaining access to American data.

-

In the European Union, judges and policymakers are pushing efforts to guard information generated within the 27-nation bloc, including tougher online privacy requirements and rules for artificial intelligence.

-

In India, lawmakers are moving to pass a law that would limit what data could leave the nation of almost 1.4 billion people.

-

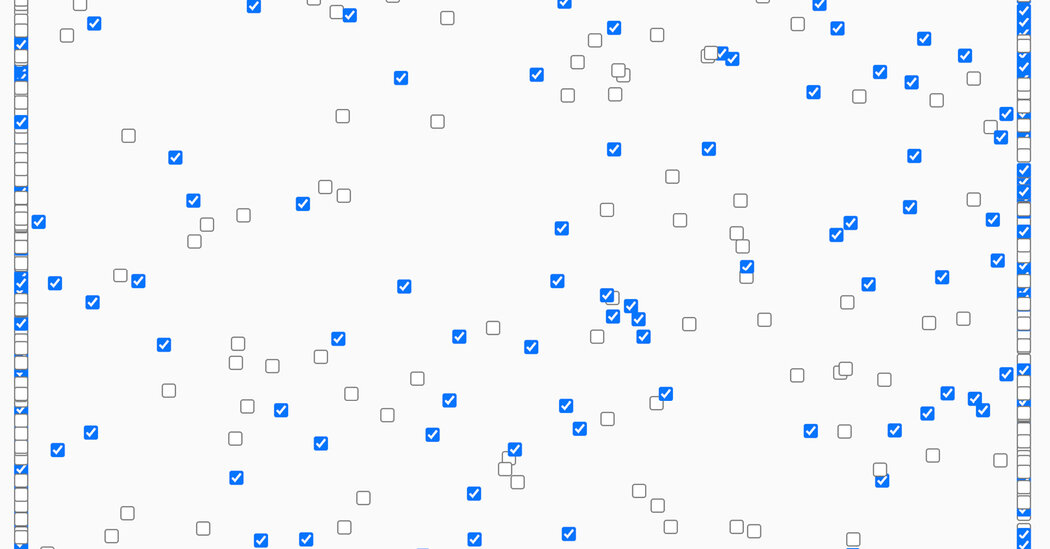

The number of laws, regulations and government policies that require digital information to be stored in a specific country more than doubled to 144 from 2017 to 2021, according to the Information Technology and Innovation Foundation.

While countries like China have long cordoned off their digital ecosystems, the imposition of more national rules on information flows is a fundamental shift in the democratic world and alters how the internet has operated since it became widely commercialized in the 1990s.

The repercussions for business operations, privacy and how law enforcement and intelligence agencies investigate crimes and run surveillance programs are far-reaching. Microsoft, Amazon and Google are offering new services to let companies store records and information within a certain territory. And the movement of data has become part of geopolitical negotiations, including a new pact for sharing information across the Atlantic that was agreed to in principle in March.

“The amount of data has become so big over the last decade that it has created pressure to bring it under sovereign control,” said Federico Fabbrini, a professor of European law at Dublin City University who edited a book on the topic and argues that data is inherently harder to regulate than physical goods.

For most people, the new restrictions are unlikely to shut down popular websites. But users might lose access to some services or features depending on where they live. Meta, Facebook’s parent company, recently said it would temporarily stop offering augmented reality filters in Texas and Illinois to avoid being sued under laws governing the use of biometric data.

The debate over restricting data echoes broader fractures in the global economy. Countries are rethinking their reliance on foreign assembly lines after supply chains sputtered in the pandemic, delaying deliveries of everything from refrigerators to F-150s. Worried that Asian computer chip producers might be vulnerable to Beijing’s influence, American and European lawmakers are pushing to build more domestic factories for the semiconductors that power thousands of products.

Shifting attitudes toward digital information are “connected to a wider trend toward economic nationalism,” said Eduardo Ustaran, a partner at Hogan Lovells, a law firm that helps companies comply with new data rules.

The core idea of “digital sovereignty” is that the digital exhaust created by a person, business or government should be stored inside the country where it originated, or at least handled in accordance with privacy and other standards set by a government. In cases where information is more sensitive, some authorities want it to be controlled by a local company, too.

That’s a shift from today. Most files were initially stored locally on personal computers and company mainframes. But as internet speeds increased and telecommunications infrastructure advanced over the past two decades, cloud computing services allowed someone in Germany to store photos on a Google server in California, or a business in Italy to run a website off Amazon Web Services operated from Seattle.

A turning point came after the national security contractor Edward Snowden leaked scores of documents in 2013 that detailed widespread American surveillance of digital communications. In Europe, concerns grew that a reliance on American companies like Facebook left Europeans vulnerable to U.S. snooping. That led to protracted legal fights over online privacy and to trans-Atlantic negotiations to safeguard communications and other information transported to American firms.

The aftershocks are still being felt.

While the United States supports a free, unregulated approach that lets data zip between democratic nations unhindered, China has been joined by Russia and others in walling off the internet and keeping data within reach to surveil citizens and suppress dissent. Europe, with heavily regulated markets and rules on data privacy, is forging another path.

In Kenya, draft rules require that information from payments systems and health services be primarily stored inside the country, according to the Information Technology and Innovation Foundation. Kazakhstan has said personal data must be kept on a server within its borders.

In the European Union, the personal data of Europeans must meet the requirements of an online privacy law, the General Data Protection Regulation, which took effect in 2018. Another draft law, the Data Act, would apply new limits on what corporate information could be made available to intelligence services and other authorities outside the bloc, even with a court order.

“It’s the same sense of the sovereign state, that we can maintain knowledge about what we do in areas that are sensitive, and that is part of what defines us,” Margrethe Vestager, the top antitrust enforcer of the European Union, said in an interview.

The Biden administration recently drafted an executive order to give the government more power to block deals involving Americans’ personal data that put national security at risk, two people familiar with the matter said. An administration official said the document, which Reuters earlier reported, was an initial draft sent to federal agencies for feedback.

But Washington has tried to keep data flowing between America and its allies. On a March trip to Brussels to coordinate a response to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, President Biden announced a new agreement to allow data from the European Union to continue flowing to the United States.

The deal was needed after the top European court struck down a previous agreement in 2020 because it did not protect European citizens from spying by American law enforcement, imperiling the operations of thousands of companies that beam data across the Atlantic.

In a joint statement in December, Gina Raimondo, the U.S. secretary of commerce, and Nadine Dorries, Britain’s top digital minister, said they hoped to counteract “the negative trends that risk closing off international data flows.” The Commerce Department also announced last month that it was joining with several Asian nations and Canada to keep digital information flowing between countries.

As new rules have been introduced, the tech industry has raised alarms. Groups representing Amazon, Apple, Google, Microsoft and Meta argued the online economy was fueled by the free flow of data. If tech companies were required to store it all locally, they could not offer the same products and services around the world, they said.

But countries nevertheless clamped down. In France and Austria, customers of Google’s internet measurement software, Google Analytics, which many websites use to collect audience figures, were told this year not to use the program anymore because it could expose the personal data of Europeans to American spying.

Last year, the French government scrapped a deal with Microsoft to handle health-related data after the authorities were criticized for awarding the contract to an American firm. Officials pledged to work with local firms instead.

Companies have adjusted. Microsoft said it was taking steps so customers could more easily keep data within certain geographical areas. Amazon Web Services, the largest cloud computing service, said it let customers control where in Europe data was stored

In France, Spain and Germany, Google Cloud has signed deals in the last year with local tech and telecom providers so customers can guarantee that a local company oversees their data while they use Google’s products.

“We want to meet them where they are,” said Ksenia Duxfield-Karyakina, who leads Google Cloud’s public policy operations in Europe.

Liam Maxwell, director of government transformation at Amazon Web Services, said in a statement that the company would adapt to European regulations but that customers should be able to buy cloud computing services based on their needs, “not limited by where the technology provider is headquartered.”

Max Schrems, an Austrian privacy activist who won lawsuits against Facebook over its data-sharing practices, said more disputes loom over digital information. He predicted the U.S.-E.U. data deal announced by Mr. Biden would be struck down again by the European Court of Justice because it still did not meet E.U. privacy standards.

“We had a time where data was not regulated at all and people did whatever they wanted,” Mr. Schrems said. “Now gradually we see that everyone tries to regulate it but regulate it differently. That’s a global issue.”

Ana Swanson contributed reporting.