Public hearings serve a subtle function. They permit the minds of the American people to acculturate to the facts and evidence. By laying out the facts that explain what Mr. Trump did, the Jan. 6 hearings can, in advance, help acclimate the public to why the Justice Department has to take criminal action against the former president. The hearings may afford the department a deeper and public explanation of its reasoning than an indictment out of the blue would offer. Public sentiment of this kind could help insulate the department against a claim that it is politically motivated. These hearings may prove to be a bridge between the Justice Department and the public.

Now consider that elusive third audience: the eyes of history. On the one hand, Mr. Garland has to fear being seen as political, and on the other, he knows that the rule of law requires him to bring an indictment if the evidence shows Mr. Trump committed one of the most serious crimes against the United States in our history. Trying to game history is a notoriously fraught enterprise, but it seems certain that if Mr. Garland is to be the first attorney general to bring criminal charges against a former president, having the facts surfaced first by a bipartisan congressional committee would be enormously helpful and provide an evidentiary record that the public today, and historians in the future, could examine.

Of course, critics will complain about the composition of the committee and the like, but those complaints, relatively speaking, are likely to be weaker than they would be if the Justice Department just investigated and prosecuted the case against the former president by itself. Here, Congress has a unique voice because the attack occurred on its members, on their soil.

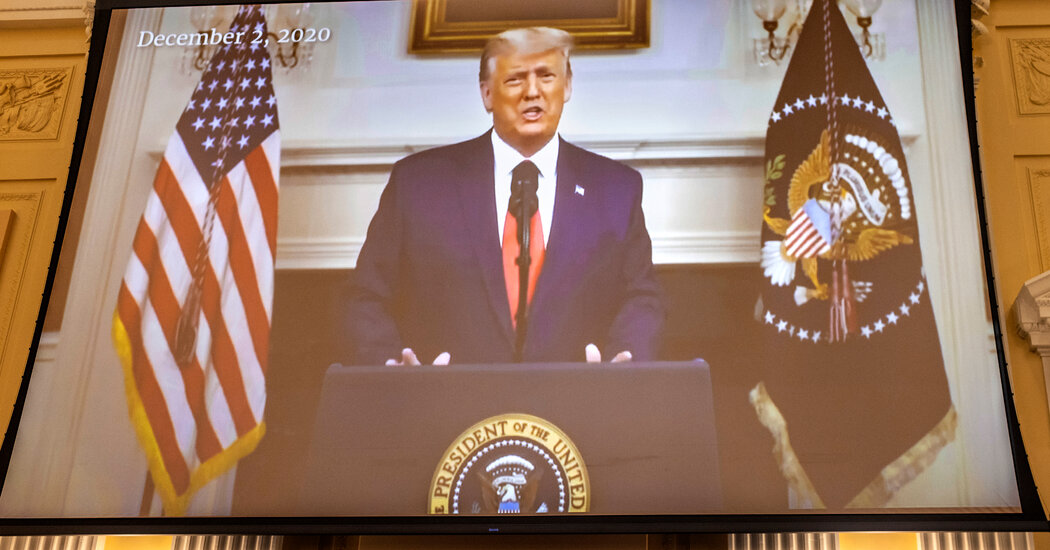

What would criminal charges against Donald Trump look like? Obstruction of an official proceeding is a serious offense that requires the prosecution to show that a defendant obstructed, or attempted to obstruct, an official proceeding and that the defendant did so corruptly. The official proceeding part of this is clear — by law, on Jan. 6, Congress and the vice president must certify the votes. There appears to have been an orchestrated plot by some to try to interfere with that certification — the question is really whether the former president was part of that plot. The committee has presented evidence suggesting that Mr. Trump, along with the lawyer John Eastman, and perhaps others such as the former White House chief of staff Mark Meadows and Jeffrey Clark, a former Justice Department official, attempted to interfere with the election certification on Jan. 6. Before the hearings, it was thought that Mr. Trump’s defense against this charge is that he genuinely believed that he had won the election and wasn’t acting “corruptly.”

The testimony in last week’s hearing cast immense doubt on that claim. Mr. Trump’s close ally, former Attorney General William Barr, testified that he told the president that arguments claiming he had won the election were “bullshit.” Mr. Trump’s daughter Ivanka testified that she believed Mr. Barr. Mr. Trump’s own election data people told him the same. Mr. Trump might try to claim he still believed the nonsense, but such an argument would be difficult to make given the array of people who told him in no uncertain terms that he had lost. Mr. Trump persisted, despite the warnings, to try to interfere with the lawful transfer of power. This looks very much like an attempt to obstruct an official proceeding.

The Justice Department could also bring the charge of “conspiracy to defraud the United States.” A charge of conspiracy requires proof that two or more people agreed to defraud the country. A key feature of conspiracy charges is that the plot need not succeed — charges are tethered to the agreement to do something illegal, not to actually pull it off. Prosecutors need not wait until the bomb goes off (or in this case, until the election results are wrongfully thrown out) before bringing charges.