Being Tina Brown, she is more often rubbing shoulder pads with the elite in the course of business: huddling under an umbrella with the historian Simon Schama en route to a 9/11 memorial, for example, or telling the sporty Mr. Parker-Bowles in 1981 that she neither hunted nor fished. (“‘Real intellectual, are you?’ he said with a slight patrician sneer.”)

Proudly, she claims to have been the first, in The Daily Beast, to reveal the extent of Jeffrey Epstein’s “depredations.” She congratulates herself, an energetic shower-upper, for turning down one invitation: to the now-infamous dinner party Epstein held in Manhattan for Andrew, attended by Woody Allen; she asked the publicist if it was a “predator’s ball.”

But as in her earlier royal biography, Brown seems perennially torn between excoriating tabloid reporters for their most egregious trespasses and reveling in their discoveries. With palpably upturned nose, she describes Matt Drudge, who outed Prince Harry’s deployment in Afghanistan even as English outlets conspired to conceal it, as a “U.S. gossip buccaneer,” while Rebekah Brooks, the former editor of the notoriously phone-hacking News of the World, is “one of the great divas” of Fleet Street, a “flamboyant social operator” with “vulpine networking skills” and a “tumbling mane of curly red hair” (signifying what, exactly?).

Brown is perfectly happy to pass on that Prince Philip once slipped a card with his private number to an anonymous socialite on the Caribbean island of Mustique, or that Princess Margaret gave mundane household items like irons and even a toilet brush as gifts to her faithful staff.

In her delicious memoir, “The Vanity Fair Diaries” (2017), Brown also seemed torn between America and England. Here, though, Old Blighty definitely wins (“wins” being a very Tina Brown term). Writing from a pandemic bunker in Santa Monica, she romanticizes rain: “the morose picnics in a squelching car park at Wimbledon; the wet carton of strawberries at Glyndebourne opera house; the sodden scuttle through the church door at Cotswold weddings; the attempt to retain something resembling a hat as the skies open at the Henley Royal Regatta.” (And here’s Schama again, texting memories of chilly Pimm’s parties on the college lawn, with “girls whose faces are turning bluer than their eye shadow.”)

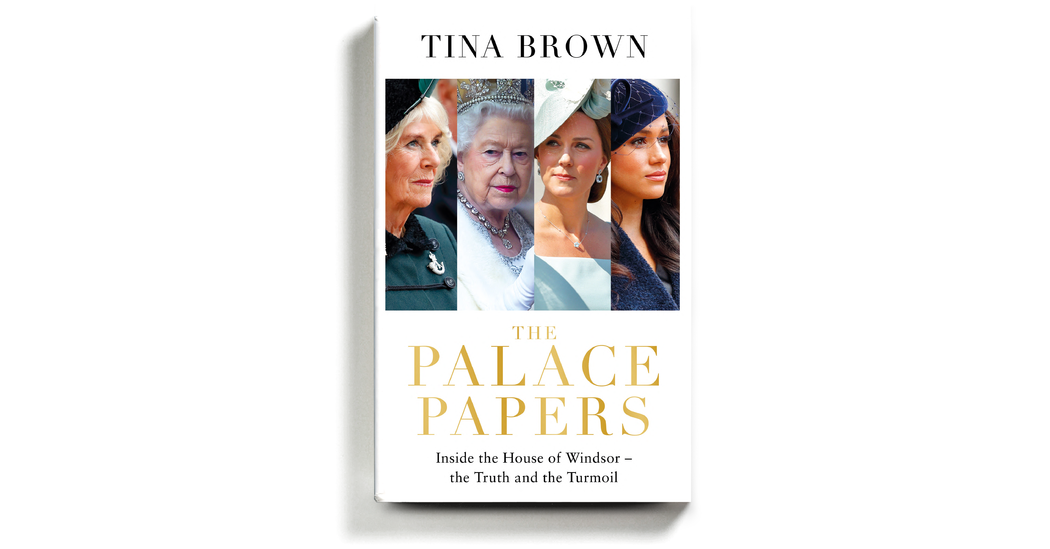

Analyzing the younger generation, the one arguably saving the “whole crumbling theme-park enterprise” of the monarchy, Brown compares Catherine, the Duchess of Cambridge, to an Anthony Trollope heroine (her birth family was “too dogged and upstanding for Dickens,” she supposes, while “George Eliot’s women, by contrast, were too complicated and reflective”). As for Meghan, the Duchess of Sussex and former actress, her story seems to emerge from “the back of bound copies of Variety” — which, given the state of print publications such as Brown used to oversee, feels like short shrift.

“The Palace Papers” isn’t juicy, exactly, nor pulpy — there’s just not enough new extracted from the whole royal mess. It’s frothy and forthright, a kind of “Keeping Up With the Windsors” with sprinkles of Keats, and like its predecessor will probably float right up the charts.