Within hours of the school shooting in Uvalde, Texas, last month, as President Biden flew home from a trip to Asia, he found himself wondering why liberal democracies like Australia, Canada and Britain can get gun violence under control, while America has tried for decades without success. “They have mental health problems. They have domestic disputes,” he said in an address to the nation later that night. “They have people who are lost. But these kinds of mass shootings never happen with the kind of frequency that they happen in America. Why?”

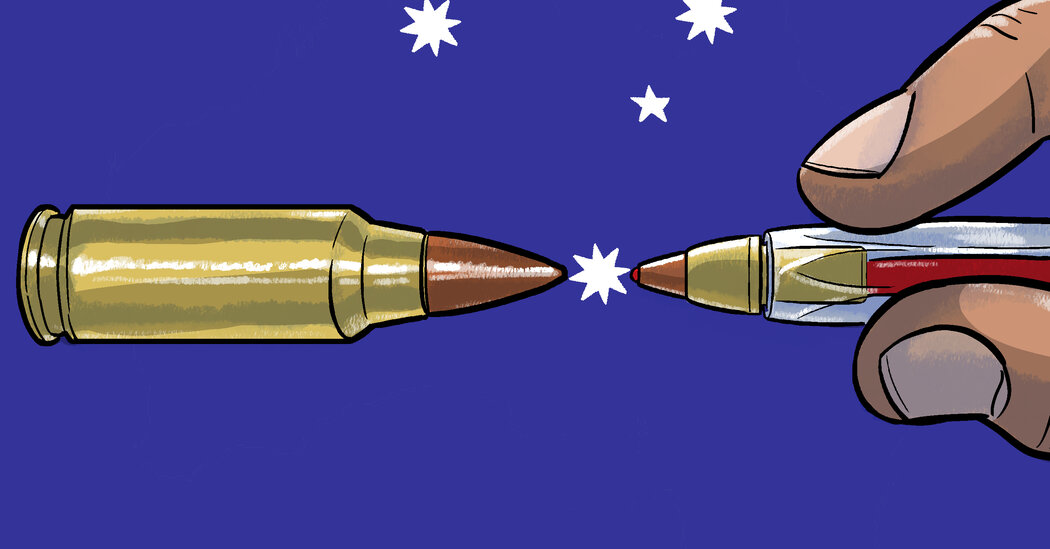

It’s easy to imagine his mind lingering on Australia. After a bitter fight with rural gun owners and conservative activists, Australia introduced sweeping measures to restrict gun access in the wake of a 1996 shooting that left 35 dead. The reforms were truly comprehensive in scope and included a ban on all automatic and semiautomatic shotguns, stringent licensing and permit requirements, and the introduction of compulsory safety courses for all gun owners, who were also required to provide a genuine reason for owning a firearm that could not include self-defense. The federal government also announced a gun amnesty and federal buyback that led to more than 650,000 weapons being surrendered to the police and destroyed.

Mass shootings and firearm deaths, including suicides, have markedly declined in the 26 years since Australia reformed its gun laws. To Mr. Biden, crossing the Pacific Ocean on Air Force One, that story must have offered a glimmer of hope, a sign that sometimes, countries can change, reducing gun violence and tragedy. If it could happen in Australia, why not in the United States?

Like America, Australia was a European settler colony, founded in the blood of massacred Indigenous people, and has a frontier myth in which guns and conquest have played a historically important cultural role. America had its cowboys, buckaroos and gunslingers; Australia its squatters, drovers and bushrangers. And like America, Australia today is a multiethnic state-based federation in which gun-friendly rural areas enjoy considerable political influence.

But these similarities tell only part of the story. Australia’s success in pushing through gun reform in the wake of the 1996 Port Arthur massacre was mostly the result of timing, luck and the idiosyncrasies of the Australian Constitution. On gun policy, the fundamental differences between Australia and America outnumber the similarities. If anything, a closer examination of Australia’s success with gun reform reveals the magnitude of the task ahead for America.

Resistance to gun reform in Australia had been fierce in the years leading up to Port Arthur. In 1987 two massacres in Melbourne left a total of 15 people dead and placed the issue of gun control firmly on the national political agenda. But the firearms lobby and lawmakers in gun-friendly states like Queensland and Tasmania worked to frustrate efforts at federal reform. Part of the problem, and an obvious point of similarity with the situation in the United States today, was that guns were mostly regulated by the states, which made reform dependent on national coordination.

Mere weeks before the Port Arthur massacre, a federal election was held that saw the conservatives — a coalition between the mostly urban and suburban center-right Liberal Party and the rural National Party — return to power after 13 years in opposition. The magnitude of their victory gave the incoming government an overwhelming mandate. Capitalizing on the depth of revulsion across Australia at the slaughter in Port Arthur, the new prime minister, John Howard, moved quickly to push through reforms, coordinated across all the states, that had stalled in the wake of earlier shootings.

The Australian gun lobby did not take these changes lying down. Gun owners protested against reform in the thousands. Effigies of the National Party leader, Tim Fischer, were burned at several rural demonstrations, and Mr. Howard took the extraordinary measure of addressing a crowd of gun supporters in the Victorian coastal town of Sale in a bulletproof vest. (He later said that he regretted wearing the vest.) But as in the United States, the 1990s in Australia were a politically more innocent time, with less polarization, more bipartisan agreement on basic issues of justice and fairness, and a less toxic media environment than the one we have become accustomed to.

It still took conviction and courage for conservative leaders to stand up to their constituents and advocate change. Mr. Fischer, in particular, faced fearsome opposition within his own party to his support for Mr. Howard’s reforms, and these divisions created real, lasting damage, permanently poisoning the country’s political discourse. But reform was still possible, thanks in large part to the shared norm of bipartisanship and the willingness of conservatives, acting on principle, to risk alienating their base.

In addition, Australia faced none of the structural or constitutional obstacles standing in the way of gun reform here in the United States. Australia does not have anything resembling the Second Amendment. It has no filibuster, no Bill of Rights and no constitutionally guaranteed right to bear arms. The Australian Constitution explicitly codifies a handful of other rights like the right to a fair trial and freedom of religion, and Australia’s High Court has ruled that the Constitution contains an implied right to freedom of political communication. But on guns, the country’s founding document has nothing to say. The great drama of contemporary Australian jurisprudence is about enshrining, rather than removing, rights within the Constitution, making the debate on individual rights and freedoms in Australia quite distinct from the one in America.

Australia loses as much as it gains from this constitutional deficiency — a point that’s often lost in American media coverage of gun policy in the emotional days that follow a mass shooting. Compared with the herculean effort that would be required to repeal the Second Amendment, Australia’s gun reforms entered into law relatively easily. But without a Bill of Rights, there’s no constitutional framework in Australia to prevent the mandatory and indefinite detention of asylum seekers, or to insulate free speech from the chilling effect of defamation suits.

The Port Arthur gunman reportedly chose his site, a former penal colony turned into an open-air museum, in part as a homage to Australia’s bloody history of colonial violence: The weakness of Australia’s architecture of express individual freedoms may have inadvertently helped put an end to frequent mass shootings, but the absence of a Bill of Rights is also, arguably, one of the reasons Indigenous Australians, those dispossessed and murdered by the same people who built Port Arthur, continue to endure life expectancy and standards of living well below the national average.

And despite the very real drop in gun violence witnessed across Australia since the mid-1990s, signs of erosion in the national framework of gun control have recently begun to emerge. There are now more guns in Australia than there were at the time of the Port Arthur massacre (3.8 million in 2020 compared with 3.2 million in 1996), and a quietly resurgent gun lobby is spending, on a per-capita basis, about as much as the N.R.A., according to a recent report. Stringent gun control standards have not stopped Australia from incubating its own radicalized killers and exporting violence abroad: The gunman in the 2019 Christchurch massacre that left 51 dead was an Australian.

So the Australian experience of gun control resists easy translation to America. But if Australia is to serve as any kind of example, it is for the bravery and principle shown by conservative and rural leaders, often at great cost to their own political fortunes, in making the case for reform to their gun-loving constituents. Character of this caliber may be far harder to extract from the ranks of today’s Republican Party than it was from Australia’s conservatives in the 1990s.

Aaron Timms (@aarontimms) is a freelance writer covering politics and culture. He is working on a book about contemporary food culture, to be published in early 2024.

The Times is committed to publishing a diversity of letters to the editor. We’d like to hear what you think about this or any of our articles. Here are some tips. And here’s our email: [email protected].

Follow The New York Times Opinion section on Facebook, Twitter (@NYTopinion) and Instagram.