The Federal Reserve lifted its key interest rate by a quarter of a percentage point on Wednesday as policymakers took their first decisive step toward trying to tame rapid inflation by cooling the economy.

The Fed had kept rates near zero since March 2020, and the decision marked its first increase since 2018. Policymakers also projected six more similarly sized increases over the course of 2022 as inflation comes in at a 40-year high, signaling that they are going to pull back support for the economy markedly.

“The economy no longer needs — or wants — these, this very highly accommodative stance,” Jerome H. Powell, the Fed chair, said during his post-meeting news conference.

The Fed is at an inflection point after two years of trying to help the economy to recover from the damage inflicted by the global pandemic. While the coronavirus continues to disrupt commerce around the world, the United States economy has staged a swift recovery. America’s job market has rebounded rapidly from steep pandemic job losses that had pushed unemployment to 14.7 percent, and businesses are now struggling to find workers.

A surge in consumer spending has helped to push the rate of inflation to levels not seen since the 1980s. Instead of echoing the anemic slog back from the 2007-9 recession — one that kept millions of applicants out of work and left inflation tepid despite years of rock-bottom rates — the pandemic bounce-back has been vigorous.

Judging by inflation, it may even have too much heat, which is why the Fed is trying to slow the economy down to a more sustainable pace.

“We’ve had price stability for a very long time, and maybe come to take it for granted — but now we see the pain,” Mr. Powell said. “We’re strongly committed, as a committee, to not allowing this higher inflation to become entrenched, and to use our tools to bring inflation back down to more normal levels.”

Mr. Powell said the labor market and economy are so strong that the Fed thinks that both can handle higher interest rates. He said he does not expect a recession this year.

“The economy, we think, can handle interest rate increases,” he said.

Higher interest rates will trickle out through markets to make mortgages, car loans and borrowing by businesses more expensive. That is expected to slow consumption and investment, reducing demand in the economy and — Fed officials hope — eventually weighing down surging prices.

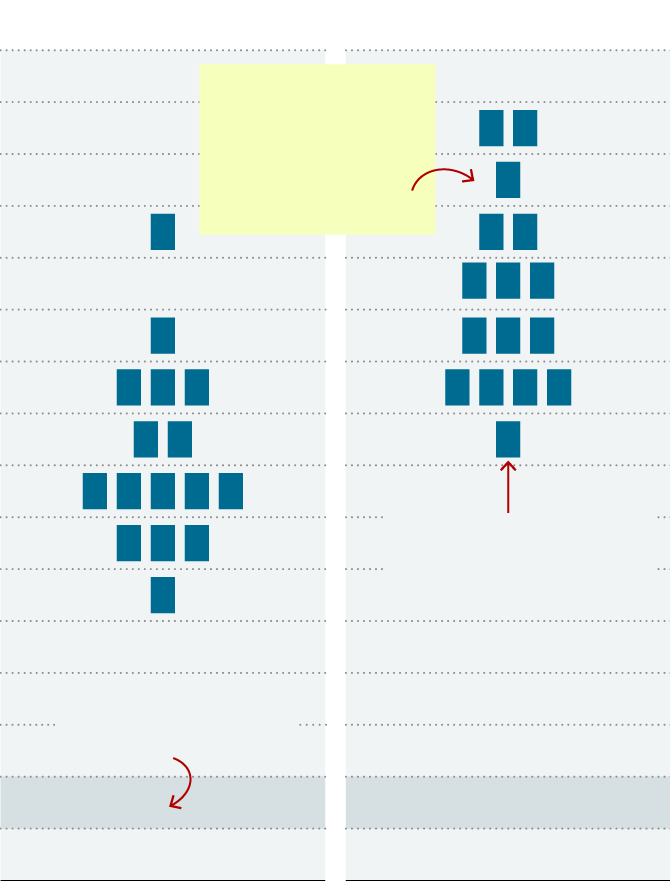

Central bankers plotted a notably more aggressive plan for controlling inflation than in December, when they last released economic projections. Officials now expect to raise rates to 2.8 percent by the end of 2023, based on the median estimate, up from 1.6 percent in their prior projections. That is high enough that, by the Fed’s own estimates, it might amount to actually tapping the brakes on the economy — not just taking a foot off the gas pedal.

End of 2023

End of 2022

Five Fed officials now think that rates could be higher than 3 percent by the end of 2023.

Each rectangle

represents one Fed

official’s judgment.

Current target rate

0.25% to 0.5% range

End of

2023

End of

2022

Each square represents one Fed official’s judgment.

Five Fed officials now think that rates could be higher than 3 percent by the end of 2023.

Current target rate

0.25% to 0.5% range

“They knew their policy didn’t match the economic backdrop, and this is catch-up,” said Priya Misra, the head of global rates strategy at TD Securities. “They’re giving a tough message that they expect they will have to slow growth to bring inflation under control.”

With the help of their policy changes, central bankers expect inflation to begin to moderate on its own this year, but they have become concerned that a meaningful deceleration will take time.

The Fed’s quarterly economic projections, released alongside the rate decision, showed that officials expected inflation to hover around 4.3 percent at the end of 2022. While that is less than 6.1 percent increase in the 12 months through January, it is well above the Fed’s goal of 2 percent.

Mr. Powell on Wednesday noted that inflation is “well above” the Fed’s target and that supply chain disruptions have been larger and longer lasting than expected. Higher energy prices are further elevating inflation just as price increases broaden beyond areas directly impacted by the pandemic, seeping into rent and other service prices.

“High inflation takes a toll on everyone, but really, especially, on people who use most of their income to buy essentials like food, housing, and transportation,” Mr. Powell said.

The Fed aims for both price stability and maximum employment, and central bank officials have indicated that the labor market is meeting that latter goal, though they hope more workers will return as fears of catching the coronavirus ease and as child-care issues tied to school shutdowns and other virus mitigation measures fade.

Unemployment has dropped sharply, job openings are plentiful, and there are too few workers to go around. A booming job market has helped to push wage growth higher because employers are competing for workers and trying to retain their existing employees by paying more. Higher compensation could fuel inflation down the road, some economists worry: It gives workers more wherewithal to spend, and it leaves firms trying to cover climbing labor costs.

From an inflation standpoint, Mr. Powell said, recent wage growth has not been sustainable.

There is a “misalignment of demand and supply, particularly in the labor market, and that is leading to wages moving up in ways that are not consistent with 2 percent inflation over time,” he said.

James Bullard, the president of the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, voted against the committee’s decision because he favored a larger interest rate increase of half a percentage point.

Mr. Bullard and some other Fed officials have argued that it would be a good idea to move rates up more quickly at first to signal that the central bank is prepared to beat back rapid price increases. But Mr. Powell made clear that, even if it is moving rates up steadily, the central bank as a whole knows it needs to act to restore price stability.

“We’re not going to let high inflation become entrenched,” Mr. Powell said.

At the same time, the Fed does not want to stoke uncertainty at a moment of towering geopolitical tensions. The Federal Open Market Committee directly addressed the possible economic implications of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in its statement.

“The invasion of Ukraine by Russia is causing tremendous human and economic hardship,” Fed officials said in their statement. “The implications for the U.S. economy are highly uncertain, but in the near term the invasion and related events are likely to create additional upward pressure on inflation and weigh on economic activity.”

While Mr. Powell reinforced time and again how important it is to do whatever it takes to get inflation under control, he also made it clear that central bankers are hoping to engineer a soft landing: A situation where they can slow growth down to a maintainable level without derailing the economy and causing a recession.

Asked about that calibration on Wednesday, Mr. Powell said that, in his view, “the probability of a recession within the next year is not particularly elevated.” He cited strong demand, a healthy labor market and other conditions that he said were “signs” that the economy will be able to flourish “in the face of less accommodative monetary policy.”

In the 1980s, the Fed pushed interest rates to high levels — above the level of inflation — in order to slow the economy and weigh down inflation. In the process, central bank policy caused a recession that pushed unemployment up to nearly 11 percent.

Most economists have said that such a painful repeat is unlikely, though many have warned that a gentle, easy end to the current inflationary burst is not assured.

“It is way too soon to say it’s a pipe dream; it’s been a crazy year,” Jason Furman, an economist at Harvard University, said earlier this week of the possibility of a soft landing. “It feels, with every passing month, increasingly unlikely.”

But the effects of the Fed’s actions to control inflation are likely to be palpable. Mortgage rates have already climbed thanks to the central bank’s signals that it would raise interest rates and, in coming months, begin to trim its balance sheet of bond holdings.

As higher rates weigh on hiring, they could eventually slow wage growth, and higher borrowing costs are likely to keep asset prices — including for stocks and homes — from rising as much as they draw buyers and investors away.