Dear Tripped Up,

My question is about airlines switching itineraries, a huge frustration for me since returning to travel after a pandemic pause. I will book a direct flight at a good time and then get an email days or weeks later with an inconvenient time change or an added layover or both. The worst was when I was planning a trip with my daughter to Tampa, Fla. In January, I booked a direct flight on Southwest Airlines that left Hartford, Conn., at 12:30 p.m. on April 17 and arrived in Tampa three hours later. Perfect. But on Feb. 15, Southwest emailed that they had moved me onto a 6:15 p.m. flight with a nearly three-hour layover in Nashville, getting me to Tampa at 1:10 a.m.! Why is this OK? It’s like I bought a nice Subaru Forester and they delivered a dilapidated and rusty Trans Am and told me it was the only option. Phoebe, Massachusetts

Dear Phoebe,

Leave it to airlines to make car dealerships seem transparent by comparison. While you could certainly sue your fictional dealer for breach of contract, the real Southwest was within their contractual rights to cancel your original flight and put you on that midnight plane from Nashville.

There’s no law against an airline unilaterally changing your itinerary, and in such cases, the main rule the U.S. government requires the airlines to follow is a flimsy one. If a carrier imposes a new itinerary on a customer that would result in a “significant delay,” the company must offer you a refund, in your case $264 each for two “Wanna Get Away” fares, Southwest’s equivalent of economy class.

They did, but as you told me over Zoom, canceling the trip wouldn’t do: You wanted to go to Florida, and had already arranged lodging. The airline gave you another option, saying you could search for an alternative Southwest itinerary, then make the change online or through customer service (which you did, painfully, as we’ll get to later).

Dan Landson, a Southwest spokesman, said that though he could not go into detail on your individual case, “there was nothing out of the ordinary that occurred.”

In fact, it was all too ordinary: From other readers, friends and members of my own family, I’ve received multiple similar tales of woe recently. But it’s hard to pin down figures on flights that change more than a week before departure. The federal government’s Bureau of Transportation Statistics does not collect such data, according to the bureau’s Ramond Robinson, nor does FlightAware, the go-to site for statistics on airline delays and cancellations, according to a company spokeswoman, Kathleen Bangs.

The six airlines (American, Delta, United, Southwest, Alaska, JetBlue) I asked would not provide specific data. To be fair, such figures would be very complicated, since many airlines schedule flights 330 days in advance that are “essentially placeholders,” said Suresh Acharya, a professor at the University of Maryland’s Robert H. Smith School of Business who has worked on airline optimization systems for two decades. The schedules solidify 90 to 180 days in advance, he said, and many changes — like a switch to a larger aircraft — are barely noticeable to customers.

But Morgan Durrant, a Delta spokesman, did say that in early 2021 “there were a lot of schedule changes, beyond anything we had seen before” as the carrier added more flights and made other adjustments to its existing schedule. That wouldn’t be surprising for Delta and other carriers during the pandemic, considering the unpredictability not only of customer demand but of crew retirements and illnesses and delays in delivering new aircraft because of supply chain disruptions.

When schedule changes do happen, said Southwest’s Mr. Landson, “we accommodate all our customers onto the next available flight. In some situations that could involve a much later flight than originally planned. It’s something that we don’t like to happen, but from time to time it does.”

If you’re annoyed now, Phoebe, you’re not going like this next bit at all. You were most likely the victim of industrywide policies that discriminate against a specific kind of customer — let’s call them “normal” — who choose the cheapest airfare they can find, no matter what airline it’s on.

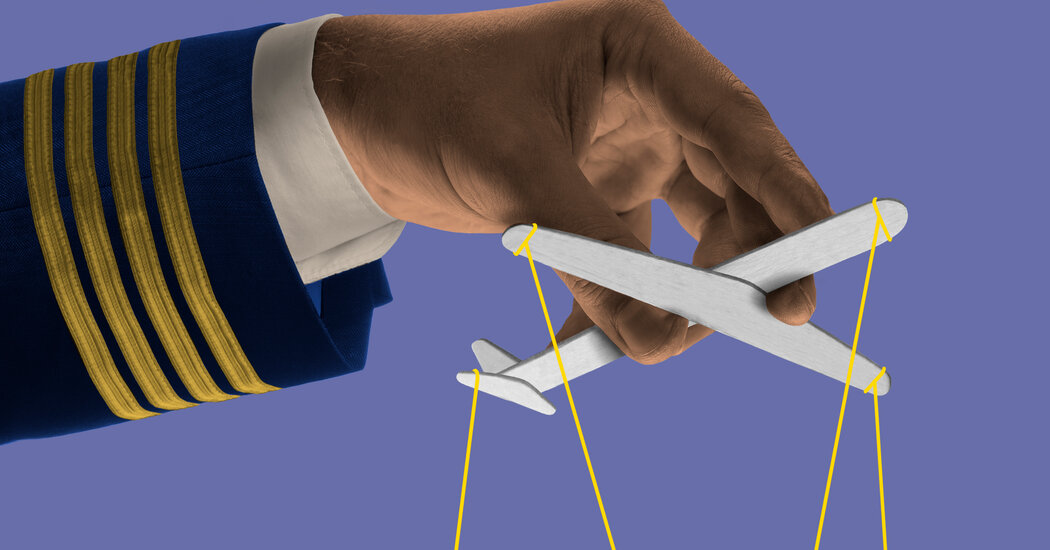

That matters because, according to Professor Acharya, airline algorithms rank passengers in order of importance, based on variables that might include fare class, loyalty status, whether you paid in miles or dollars, how big your group is and whether you’re an airline employee.

If you need advice about a best-laid travel plan that went awry, send an email to trippedup@nytimes.com.

As you told me, Phoebe, you were able to find two other options on the Southwest website that worked better for you. The best was a midday flight from just-as-convenient (for you) Providence that almost precisely matched your original itinerary, the other a direct evening flight from Hartford on your desired travel date. You were dismayed when the site would not let you on the Providence flight, and in a vexing, eight-hour, on-and-off Twitter conversation with Southwest the next day, you learned it was because Providence and Hartford were not “co-terminals” — a frustrating piece of jargon meaning that the airline did not consider them interchangeable. But you ultimately rebooked that evening flight from Hartford.

That’s annoying, but the big mystery to me is why weren’t you automatically rebooked on that evening flight. Mr. Landson surmised that by the time your number came up in the seat reassignment process, others had filled in the open seats on the flight, but spots opened up by the time you looked.

When I presented that answer to Professor Archarya, he warned that there might also be a “shady” possibility. Airlines sometimes tweak algorithms to give weight to revenue considerations over customer satisfaction, he said, and it was theoretically possible Southwest held some of those Hartford to Tampa seats open to maximize revenue by selling later. Mr. Landson objected to that, saying in cases like this one Southwest always books passengers on the next available flight if there is enough room for their group.

Going forward, you and other readers can take measures to minimize such frustrations, though in most cases they will cost time, money or maybe both.

One option is to simply book closer to the flight date. As Mr. Acharya said, schedules become much more settled by 90 days out, so the later you book after that, the lower the chance of changes. Of course this doesn’t help in the case of weather problems and Covid spikes that knock out crews, and you may miss out on early bird prices.

Another option, one that I am now considering for myself, is to abandon the “cheapest fare wins” strategy. Favor the airline that flies most on routes you frequent, spending $20 or even $50 extra as you work your way toward loyalty status. (Airline-branded credit cards can help, although they have their own issues.) Status also helps when flights are canceled last minute as well.

Third, and possibly only worth it when you have a narrow window in which you must arrive for a wedding or another important event, is what George Hobica, founder of airfarewatchdog.com, suggests: buy a second, fully refundable seat on a different airline at around the same time. Refundable flights are more expensive, but you can cancel and receive your money back anytime before your scheduled departure. So if your original ticket is changed to an unacceptable time, you get a refund on that one and fly your backup; if your original does not change, you cancel your refundable backup.

Of course, the line between corporate greed and customer satisfaction is hidden deep within secret airline algorithms. But it struck me that we could solve at least part of the problem if airlines thought we’d be willing to pay more across the board for them to build more slack into the system. I mentioned that to Ms. Bangs of FlightAware.

“We have a system like that,” she joked. “It’s called private aviation.”