WASHINGTON — For weeks, Stephen K. Bannon, a former top adviser to President Donald J. Trump, delivered heated speeches about his pending trial, promising at one point to go “medieval” on the prosecutors who had charged him with refusing to comply with a subpoena issued by the House select committee investigating the Jan. 6 attack on the Capitol.

But once in court, he decided not to testify or mount any other sort of defense, and on Friday, Mr. Bannon was convicted of two counts of contempt of Congress.

The jury’s verdict, reached after less than three hours of deliberations, came one day after video of Mr. Bannon briefly appeared in a public hearing of the House committee he had snubbed. Investigators played a clip of him saying that Mr. Trump had planned to declare victory in the 2020 election, no matter what the results were.

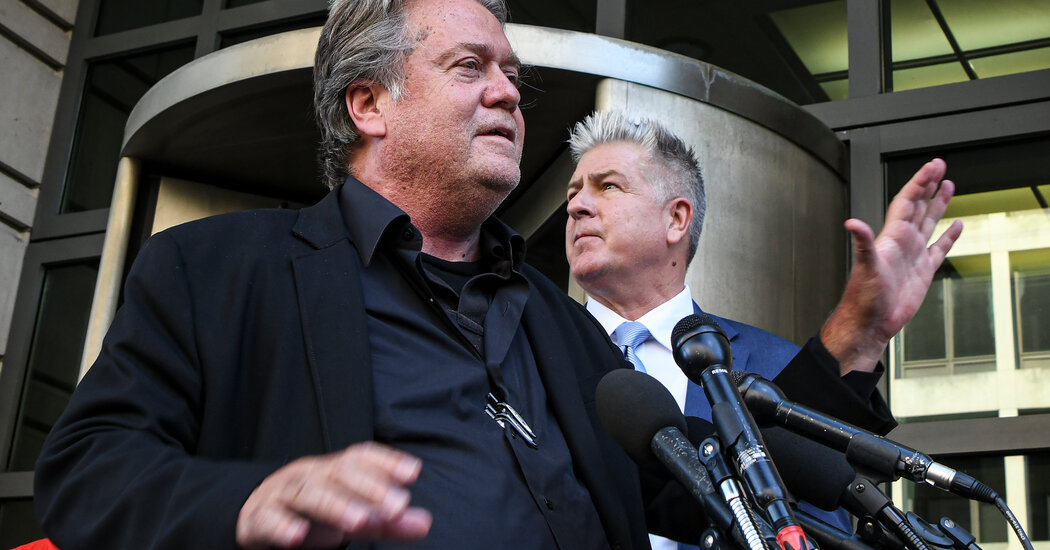

Mr. Bannon, 68, remained defiant in remarks outside the courthouse, saying the prosecution’s assertion that he had chosen “allegiance to Donald Trump over compliance with the law” was correct, but omitted an important detail.

“I stand with Trump and the Constitution,” Mr. Bannon said. “I will never back off that.”

Judge Carl J. Nichols set a sentencing date in late October but David I. Schoen, a lawyer for Mr. Bannon, said they would appeal the guilty verdict.

Mr. Bannon’s conviction was the latest turn in a tumultuous political career that over the years saw him take a leading role in bringing together right-wing media, presidential politics and America First-style populism. He helped found the website Breitbart News, which he once described as a “platform for the alt-right,” a loosely affiliated collection of racists, misogynists and Islamophobes that rose to prominence around the time of Mr. Trump’s first campaign.

Beginning in 2016, Mr. Bannon served as the campaign’s chief architect, helping Mr. Trump craft his divisive, populist message. He was brought into the White House after Mr. Trump’s victory to work as a strategist and senior counselor to the president, but lasted only seven months before returning to Breitbart.

In August 2020, Mr. Bannon was arrested on the $35 million, 150-foot yacht belonging to one of his business associates, the fugitive Chinese billionaire Guo Wengui. Federal prosecutors in New York accused him of defrauding donors to a private fund-raising effort called We Build the Wall, which was intended to bolster Mr. Trump’s signature initiative along the Mexican border.

Mr. Trump ultimately pardoned Mr. Bannon in his final hours in office.

After Mr. Trump’s defeat in the 2020 election, Mr. Bannon once again came to his aid. He worked with Peter Navarro, a White House adviser, to devise a strategy to keep the president in office that they called the “Green Bay Sweep.” The plan called for Republican members of the House and Senate to block the counting of Electoral College votes on Jan. 6, 2021, so that lawmakers in key swing states could decertify the vote results in their states and hand Mr. Trump a victory.

Mr. Bannon’s conviction was the first of a close aide to Mr. Trump to result from one of the chief investigations into the Capitol attack. Mr. Navarro has also been charged with contempt after defying a subpoena from the House committee and is scheduled to go on trial in November.

Key Revelations From the Jan. 6 Hearings

Mr. Bannon, who left the White House in 2017, was indicted last November. He has remained free without bail, as prosecutors did not ask the court to detain him.

Contempt of Congress is a misdemeanor, with each count punishable by a fine and a maximum of 12 months in prison. At the time, the filing of charges against him was widely seen as proof that the Justice Department could take an aggressive stance against some of Mr. Trump’s top allies as the House seeks to develop a fuller picture of the actions of the former president and his inner circle before and during the attack.

Despite the legal wranglings that preceded his trial, Mr. Bannon’s guilt or innocence ultimately turned on a straightforward question: whether he had defied the House committee by flouting its subpoena. “This case is not complicated, but it is important,” Molly Gaston, a federal prosecutor, said in a closing statement on Friday.

Ms. Gaston told the jury that the House committee had wanted to ask Mr. Bannon about his presence at the Willard Hotel before the Capitol attack, where plans to overturn the election were discussed, and about his statement the day before the assault that “all hell” was going to break loose on Jan. 6.

But, she argued, Mr. Bannon had blatantly disregarded the committee’s demands in order to protect his former boss.

During his own summation, M. Evan Corcoran, one of Mr. Bannon’s lawyers, sought to argue that the subpoena his client had received had been improperly signed by the committee, adding for the jury that Mr. Bannon had not intentionally failed to comply with it. Mr. Corcoran also noted, trying to suggest a whiff of impropriety, that a prosecutor on the case and one of the government’s witnesses had belonged to the same book club.

Before court started on Friday, Mr. Bannon’s legal team made a written request to Judge Nichols to ask the jurors if they had watched what the team described as the “highly inflammatory segment” of the prime-time committee hearing on Thursday that had featured Mr. Bannon. But Judge Nichols declined to poll the jurors.

Like many defendants, Mr. Bannon did not mount a defense case for the jury, deciding instead to rely on cross-examining the prosecution’s two witnesses: a lawyer for the committee and an F.B.I. agent who had worked on the case.

Last week, the lawyers suggested that Mr. Bannon might take the stand, but in the end he decided against testifying.

Testimony in the trial ended on Wednesday as the prosecution rested its case against Mr. Bannon, arguing that he had willfully ignored the subpoena for both records and testimony even after being warned that he could face criminal charges.

The proceeding came down to the simple fact that Mr. Bannon had “thumbed his nose” at the law, prosecutors said.

Mr. Bannon’s lawyers countered that the deadlines set by the committee to receive their client’s testimony and documents were flexible, one of the few lines of argument Judge Nichols had left open to the defense. In pretrial rulings, Judge Nichols had said that the lawyers were not allowed to argue to the jury that Mr. Bannon had received legal advice to disregard the subpoena or claim that Mr. Trump had personally authorized him to do so.

“Mr. Bannon has a full story for why he didn’t show up — his advice of counsel, the invocation of executive privilege, questions about its validity and so on,” Mr. Schoen, the lawyer for Mr. Bannon, argued in court this week before the trial had begun. “All of these defenses and his story of the case have been barred by the court at the government’s request.”

With his options limited, Mr. Corcoran contended during the trial that the subpoena and the prosecution’s case itself were politically motivated.

Before the trial began, Mr. Bannon reversed course and offered to testify before the Jan. 6 committee. But prosecutors have portrayed that move as a last-ditch attempt to avoid the charges.

Judge Nichols also denied multiple requests from the defense to delay the trial, first stemming from concerns that the public hearings held by the Jan. 6 committee and continuous news coverage of the trial would taint the jury pool and later because the defense said it was unprepared to argue its case after the constraints Judge Nichols had placed on its potential arguments.