LOS ANGELES — On a clear December morning, Los Angeles’s greatest hits shine from the roof of the Audrey Irmas Pavilion: You can see the Hollywood sign, the Griffith Park Observatory, even a snowy Mount Baldy, all without squinting.

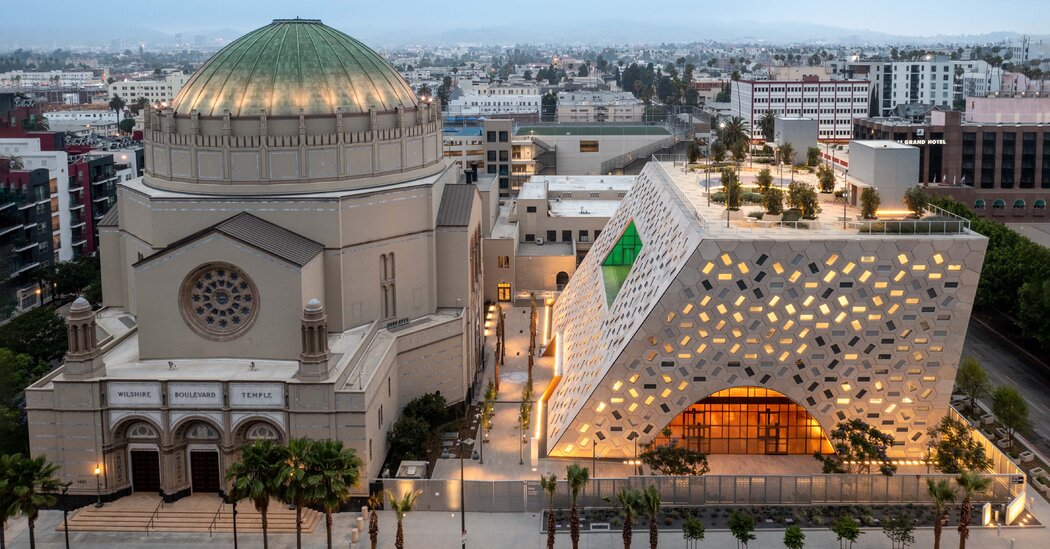

The pavilion, a futuristic, three-story trapezoid with a wood-paneled event center, sunken garden and rooftop terrace in the center of the city, will serve Koreatown, which is among the city’s densest and most diverse neighborhoods.

It is first, though, a community space for the Wilshire Boulevard Temple, the Byzantine-Romanesque domed synagogue next to the pavilion — the final piece of the temple’s long expansion plan.

The temple’s dome was modeled after Rome’s Pantheon. It crowns the sanctuary, whose 1929 construction was supported by heavyweights like the Warner brothers, the Universal Pictures founder Carl Laemmle, and the M.G.M. co-founder Louis B. Mayer, who donated wraparound murals by the artist Hugo Ballin, coffered ceilings, a heavenly oculus and stained glass windows.

But in the 2000s, as the congregation was shrinking and the grounds were degrading, some temple leaders and members thought it might make sense to sell the building.

The senior rabbi of the temple, Steven Leder, spent six years raising $120 million. By 2011, there were renovation plans for the temple from the architect Brenda Levin, and two years later, the oldest glass studio in Los Angeles, Judson, had restored the sanctuary’s neo-Gothic windows, the sculptor Lita Albuquerque had designed a memorial wall and the artist Jenny Holzer had crafted a series of benches.

The pavilion was next, in an adjacent parking lot owned by the temple, but Rabbi Leder needed the right architect: a modernist who respected tradition.

Enter the philanthropist Eli Broad, who reshaped this city’s cultural footprint and left its future in question after his death last year.

Broad, the billionaire developer who spent decades raising the profile of the city with his wife, Edythe, met with Rabbi Leder in 2015, a few years before retiring. Rabbi Leder said: “I asked Eli: ‘Will one of the world’s great architects design a building for a synagogue?’ He looked at me and said: ‘For that sanctuary, on Wilshire Boulevard, in Los Angeles? They’re all going to want to do it.’”

So the pavilion was born. Designed by the Office for Metropolitan Art — the firm founded by the Pritzker Prize-winning Rem Koolhaas — the project also paved the way for another donor, Wallis Annenberg, to fulfill a longstanding vision she had for the city: for a center to help older people find community.

In years past, clashes with Broad had cost Koolhaas two chances to work with the philanthropist: to design the downtown museum, the Broad, and to remodel and expand the Los Angeles County Museum of Art. Broad, a trustee at LACMA, initially supported a structure that Koolhaas proposed but then changed his mind. He went instead with Renzo Piano, in what would effectively become the Broad Contemporary Art Museum at LACMA.

“We won the LACMA bid but Eli kicked Rem out and hired Renzo,” Shohei Shigematsu, Koolhaas’s longtime OMA partner, said in an interview.

Koolhaas, 77, is known for theories celebrating urban chaos and works like the China Central Television headquarters in Beijing, a skyscraper that some saw as glorifying a Chinese propaganda machine but that a New York Times critic called “one of the most beguiling and powerful works I’ve seen in a lifetime of looking at architecture.” The artist and architect Hiroshi Sugimoto recently described Koolhaas’s approach as full of “bad will.”

But, Koolhaas said in an interview, provocation is no longer his goal. “Maybe 20 years ago,” he said.

It “now feels a little out of place given that there are so many urgent issues to consider,” he added.

Koolhaas calls Los Angeles a favorite city — he lived here in 1974 when he was writing a screenplay. Of his rejected design, he said, “LACMA is maybe something that was not really appreciated.”

Joe Day, a designer and architectural theorist in Los Angeles, said, “Koolhaas has often fallen prey to having a compelling idea and the world or his patrons struggle to catch up.”

Broad had other disagreements, including with the architect Frank Gehry, who refused to finish a remodel of Broad’s home. (Yet years later, Broad supported Gehry’s design for Disney Hall.)

For the pavilion, Broad in 2015 advised holding an international competition, for which he footed the bill.

A 15-person panel was assembled for this competition and it whittled down 25 firms to four, whom Broad paid $100,000 each.

Then OMA was chosen. The temple then received a $30 million pledge from the philanthropist Audrey Irmas, after the $70.5 million sale of her Cy Twombly “blackboard” painting, and Rabbi Leder continued to fund-raise.

Shigematsu, now 48, said, “It was a strange turn of events.”

Recalling the failures presaging the contest, he said, “To be invited to the temple competition by Eli — and to get selected. We were surprised.”

Koolhaas called his interactions with Broad for the temple cordial, his support “extremely important.” But when the firm’s project was announced, the temple’s congregants worried that Koolhaas’s style would diminish the traditional domed building.

Six years later, the pavilion, which in all cost $95 million, is warm and vibrant, with 1,230 hexagonal glass fiber reinforced concrete panels that give a kaleidoscope effect. But perhaps most interesting to some would be that the Broad-Koolhaas collaboration doesn’t involve a Koolhaas building.

“A lot of people are confused,” Shigematsu said. “OMA is in a transitional moment. It used to be Rem as the leader but now it’s a partnership. I’m the design lead here. Unfortunately, most people write it’s Rem’s building.”

“In this case, he wasn’t really involved,” Shigematsu added. “He designed the mezuzas,” on the pavilion’s door frames, “and it was a way to show we can collaborate within the partnership — and the temple was quite happy.”

Koolhaas, who had been unable to leave Europe for a long period because of Covid-19 travel restrictions, said, “I was involved from a distance.”

“The obsession with architecture as a work with a single genius — I think it’s completely out of place,” he added.

Doug Suisman, an architect who is the author of “Los Angeles Boulevard,” called the result of the collaboration “a generational shift within OMA, from the gleeful aggressiveness of Rem Koolhaas to an almost contemplative calm of Shohei Shigematsu.”

Koolhaas said: “My partners have large independence, and in a way now I have great independence. It’s a quite intense effort to inject your vision in every project.”

In 2018, OMA’s design for the pavilion was leaked, and as the philanthropist Wallis Annenberg was leafing through her paper, she read about the temple project and its architects, location and leadership. “Bull’s-eye,” she said.

For years, she said, she had wondered, “What if I was alone with no support system?”

“Even at a young age, I noticed older people by themselves in restaurants, theaters, parks, and it broke my heart,” she said, citing the psychologist Erik Erikson’s concept of development extending to old age. “Why aren’t we making these people part of a community?”

Annenberg contributed $15 million to complete the pavilion and another $3 million on a third-floor, 7,000-square-foot creative center, called GenSpace. It is a cultural space for older adults.

“Lectures, movies, experiences — that sets it apart and that’s what seniors want,” said Lila Guirguis, the executive director of the Karsh Center, a nonprofit organization founded by the temple for underserved people of all ages that is partnering with GenSpace.

Membership is $10 monthly, with a sliding scale, and classes have already been offered online. (The spread of the Omicron variant has delayed GenSpace’s hard opening.) The center has the feel of a start-up, with interior design by the firm Stadler &, interactive art by the Japanese collective teamLab, and Maira Kalman wallpaper, as well as a workout studio and a rooftop terrace.

Annenberg, 82, is the chairwoman and president of her family’s foundation, which has given over $1 billion to about 3,800 nonprofits since she assumed leadership in 2009. “I have opportunities to thrive and live a semi-vibrant life and connect with people of all ages,” she said.

“But,” she added, “I’ve slowed down a lot; I have tremendous mobility issues. I think the pandemic has taught us all how critical connectivity is.”

Annenberg’s grandfather Moses came to America in 1885, and started a publishing empire. Her father, Walter, began the foundation that has helped countless educational, arts, medical and environmental projects.

Wallis, who has in a Vanity Fair interview jokingly reminded people that her name is not Wallet, is an heiress, but her life has not been carefree: Her brother, Roger, committed suicide; her marriage crumbled, and she lost custody of her children for a time.

Today, 27 institutions in the Los Angeles area carry her name (even more carry the family name). She sees GenSpace as “a role model for people to follow.”

Longevity and elder care are growing issues. Over 7,000 Californians turn 65 each week, according to the state’s recent master plan on aging, and the state has the nation’s second-highest life expectancy. GenSpace’s director, Jennifer Wong, who was a co-author of the master plan, said that she anticipates conversations at the center that cut across ethnic and generational lines. The center also has as its mission fighting bias and isolation that the elderly may face.

As for Annenberg, she sees this as part of her legacy — work that will carry on after she is gone. “I’m not going to be here forever,” she said.

“Older Americans aren’t the past,” she added. “They’re the future. We have to open our eyes.”