Before boarding his flight from Los Angeles to the Chinese city of Guangzhou, Xue Liangquan, a California-based lawyer, knew he was in for a bit of a headache.

To visit his parents in eastern Shandong Province in January, for the first time since the coronavirus pandemic began, Mr. Xue, 37, had already shelled out $7,600 for airfare. He had submitted negative test results to the Chinese authorities, as required for entry. Upon arrival, he would have to do three weeks of quarantine.

Even so, he never could have foreseen just how much of an ordeal he was about to suffer. Mr. Xue, through a Kafka-esque streak of bad luck and run-ins with China’s unbending virus rules, would spend the next three months in quarantine, bouncing between hospitals and hotel rooms.

Released from one round of isolation, he would immediately find himself ordered into another. By the time of his return flight, he would have had about two days of freedom in China. He would not have seen his parents at all.

“It was like a nightmare,” Mr. Xue said in an interview from California, where he returned earlier this month and wrote a blog post on the social media platform WeChat about his experience.

“I thought, if I didn’t write it down, it would feel even more like a nightmare: As if I had a bad dream in my bed in Los Angeles on Jan. 1, woke up on April 1 and was still in my bed in Los Angeles, and the time in between had just disappeared.”

China has for more than two years held to some of the world’s toughest quarantine restrictions, in its unswerving pursuit of “zero Covid.” Wuhan, the city where the pandemic began, was locked down for two months. Shanghai, currently battling its worst Covid outbreak, has been at a standstill for two weeks. International travel to and from China is nearly nonexistent.

The restrictions have been a source of much debate, both at home and overseas. Even Mr. Xue’s blog post, which was widely shared on Chinese social media, drew polarizing reactions: Some readers expressed horror, others called it prime material for a comedy movie, and still others attacked Mr. Xue for returning to China at all, decrying it as a selfish decision that risked bringing the virus into the country.

Mr. Xue, who was born in China and moved to the United States seven years ago, remains determinedly neutral.

“I don’t blame anyone: no person, government, organization,” he said. “I can only blame myself, for having such bad luck.”

His ill-fated journey began on Jan. 2, when, armed with a negative Covid test, he took off from Los Angeles. In Guangzhou, he was tested again, then sent to a quarantine hotel. His room was a pleasant surprise — it even had a large Jacuzzi. Perhaps the next few weeks would be like a mini-vacation, he thought.

It was not to be. Just as he was about to lie down to rest, he received a phone call informing him that his airport test was positive. He would be transferred to a hospital by ambulance.

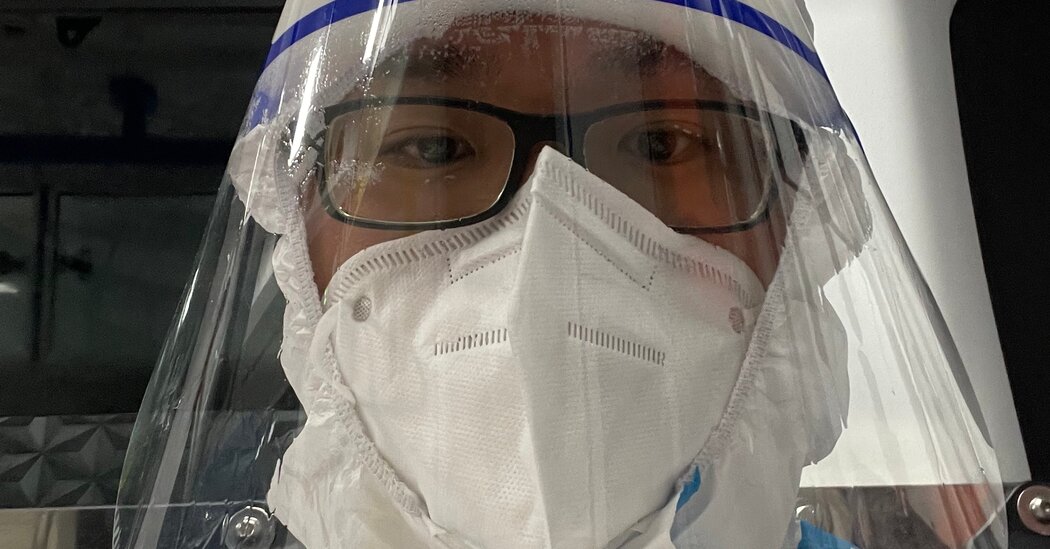

Mr. Xue struggled into full-body protective gear that was left at his door. His breath fogged up his glasses and the face covering. “All I could see were the drops of water endlessly dripping down,” he wrote in his blog post.

He spent the next four weeks in a hospital, sharing a room with two other patients. He video-chatted with his parents every day, reassuring them that his symptoms were mild. He took photographs of his food to show them that he was eating all right. (In reality, Mr. Xue said, he took photos only of the best meals, so they would not worry.) He worked remotely for the law firm he founded.

On Jan. 31, the eve of Lunar New Year — China’s biggest holiday, which he had hoped to spend with his family — he watched the Spring Festival Gala, a televised extravaganza, on his tablet, alone in bed.

He had little contact with his fellow patients; no one was really in the mood to socialize, Mr. Xue said.

“At first, I felt pretty depressed,” he said. “All you can do is suffer. And, within your limited capacity, arrange your daily life as best you can. When you should shower, shower. When you should brush your teeth, brush.”

On Feb. 1, he was released from the hospital — and transferred to another one, for recovered patients, for two more weeks of “medical observation.”

But even after that, his ordeal was only halfway over.

After leaving the second hospital, Mr. Xue flew to Shanghai, where he had relatives. (He had given up on going to Shandong, as its quarantine rules were stricter than Shanghai’s at the time.) The test he took there, as required by local rules, was negative. For the first time in a month, he was free.

It lasted two days. On Feb. 19, Guangzhou health officials notified him that the lone other man with whom he had shared a bus from the last hospital had tested positive. That made Mr. Xue a close contact, meaning he now had to spend 14 days in hotel quarantine.

Then, on March 6 — the very day he was to be released from that quarantine — he received another call. He himself had now tested positive again, an official told him. Mr. Xue demanded proof, but the official refused, he said.

“The hardest part for me was the lack of certainty,” he said. “Each time I thought one stage had ended, and I was about to be free, the nightmare would return.”

And so began anew a procedure with which Mr. Xue was now all too familiar. Two more weeks at a medical facility. Two weeks after that at a hotel.

Finally, on March 31, Mr. Xue was set free, for real. But, exhausted by his ordeal, he had given up hope of seeing his parents and booked an April 1 flight back to the United States. The only relative he saw was his younger brother, in Shanghai.

Once, Mr. Xue would have been devastated: Living overseas, he said, he had long cherished, even fixated on, the idea of home. But weeks of isolation had given him a new perspective.

“We want to go home and reunite, to let our lives that have split apart intersect again. But if we’ve tried, and didn’t succeed, then I don’t have any regrets,” he said. “I still have to be accountable for myself. I can’t, for the sake of this reunion, sacrifice another three months.”

Mr. Xue is sympathetic to China’s controls. The country’s population is so large and so quickly aging, he said, that living with the virus could be disastrous.

But he himself will not be trying to return again until restrictions have eased.

“Otherwise, I think I would still feel sort of traumatized,” he said. “I really am rather scared.”

Liu Yi and Joy Dong contributed research.