Garth Hudson, the stoic multi-instrumentalist and co-founder of the Canadian roots-rock group the Band, died Tuesday at a nursing facility in his adopted hometown of Woodstock, N.Y. He was 87.

Throughout a lifetime of music, Hudson — whose bushy beard, professorial demeanor and musical chops added a scholarly gravitas to the Band via his work on electrical organ, accordion and saxophone — performed with artists together with Bob Dylan, Emmylou Harris, Neil Diamond, Norah Jones, Neko Case and Ringo Starr.

Although his bandmates did many of the speaking in interviews and onstage, Hudson’s musical textures, many impressed by previous Canadian and American folks songs, had been important components of the Band’s sound on classic-rock requirements together with “The Weight,” “The Night They Drove Old Dixie Down” and “The Shape I’m In.”

Famously, Hudson served as tape recorder operator and de facto engineer when, in 1967, Dylan moved to Saugerties, N.Y., to get better from a motorbike crash and commenced woodshedding classes with Hudson’s bandmates Robbie Robertson, Rick Danko, Levon Helm and Richard Manuel within the basement of a home they dubbed Massive Pink. Hudson’s recordings served as the premise of each for the seminal Dylan and the Band album “The Basement Tapes,” formally launched in 1975, and “Music From Big Pink,” the Band’s 1967 debut album.

Hudson’s stately bearing belied his roots as a rock ’n’ curler. Anybody who has seen his work in “The Last Waltz,” Martin Scorsese’s 1978 documentary on the Band’s last efficiency, will recall Hudson’s abilities. Trying extra like a nineteenth century senator than a late-Sixties hitmaker, in the course of the movie he approached the microphone for an alto sax solo in “It Makes No Difference” as if stepping to a lectern to present a speech. When he did, he held the ground with easy elocution.

“Different musical styles are just like different languages,” Hudson advised Canada’s Globe and Mail in a uncommon 2002 interview. “I’m able to play a lot of instruments so I can learn the languages.” He added, “It’s all country music; it just depends on what country we’re talking about.”

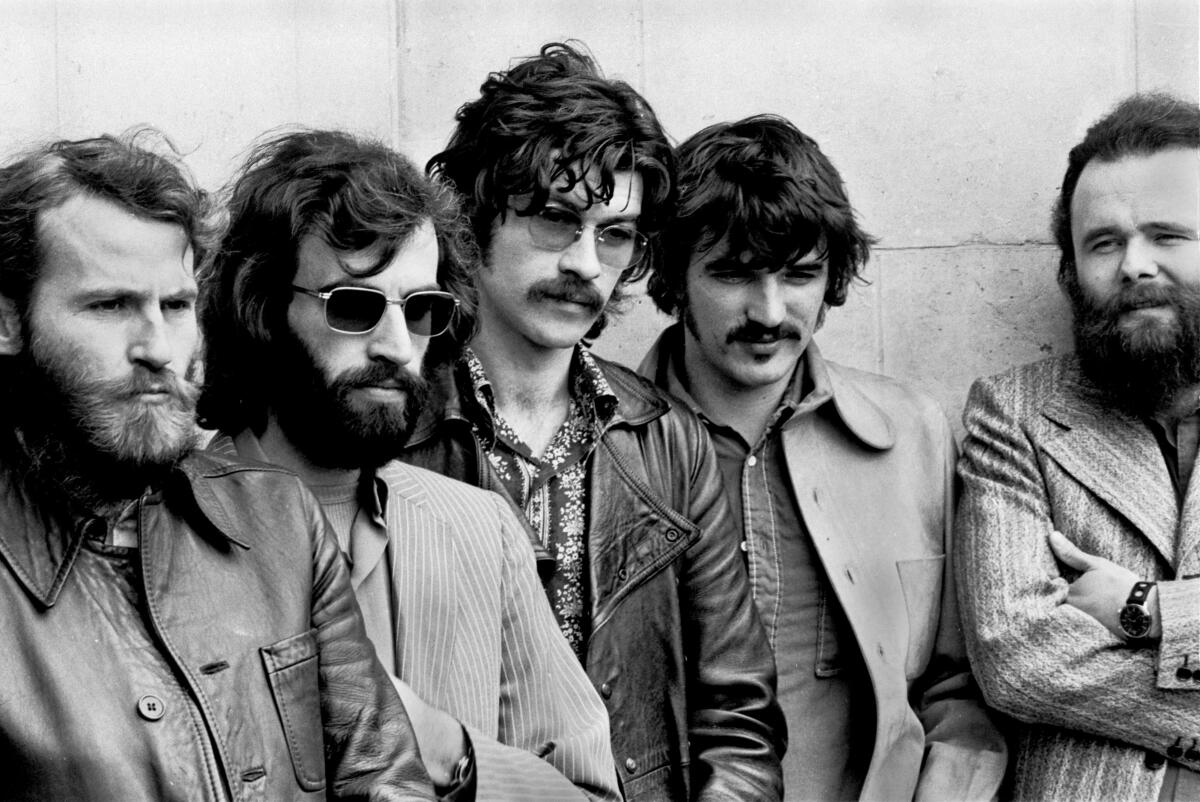

The Band, from left, Garth Hudson, Rick Danko, Richard Manuel, Levon Helm and Robbie Robertson.

(GAB Archive / Redferns)

Born on Aug. 2, 1937, in Windsor, Ontario, Eric Garth Hudson was the son of a musically inclined father, Fred Hudson, who was a fighter pilot in World Struggle I earlier than turning into a farm inspector, and an accordion- and piano-playing mom, Olive Hudson, who began instructing her son each devices when he was a toddler.

Along with formal coaching, like many adolescents on the time Hudson’s musical tastes had been knowledgeable by Alan Freed’s “Moondog Matinee” rock ’n’ roll radio present, which was broadcast from Cleveland. “That’s when I realized there were people over there having more fun than I was,” Hudson mentioned, as quoted in Greil Marcus’ tome “Mystery Train.“ Hudson joined his first band when he was 12 and spent his teens playing piano and saxophone in rock and jazz outfits.

In 1957, he co-founded the Silhouettes, which morphed into Paul London and the Capers. The band occasionally ventured south to Chicago and Detroit, and even traveled west during one tour to play the famed jazz club the Lighthouse in Hermosa Beach. “We’d played a couple of months before the Border Patrol told us to go home,” Hudson, who spoke with a measured Northern drawl when he bothered to speak in public in any respect, advised the Globe and Mail. “They told us we had to get permanent work visas, which at that time they mostly gave to hockey players and wrestlers.”

In late Fifties Toronto, Hudson met the 4 different members of the Band once they had been employed to tour with rock ’n’ roll singer Ronnie Hawkins. Inside a number of years, the Hawks gelled right into a studied, tight backing band. As they gained momentum, they left Hawkins in 1963 to tour on their very own, trekking via southern Canada and throughout the border to golf equipment on the East Coast. Dylan related with the longer term Band throughout one in all these stops and invited them to tour Europe with him. Throughout these excursions, Dylan formally “went electric” for half of every live performance.

Garth Hudson performs throughout “The Last Waltz” on Nov. 25, 1976 in San Francisco.

(Ed Perlstein / Redferns)

That’s Hudson powering his trademark Lowrey organ via Dylan’s searing efficiency of “Like a Rolling Stone” on the Free Commerce Corridor in Manchester, England, on Might 17, 1966. He hit these overpowering first notes after an offended folk-loving fan had screamed “Judas!” at Dylan for betraying his folks roots. That outburst was due in no small half to Hudson’s pipe-rattling organ fills.

Hudson and the remainder of the Band descended on Dylan’s house in Saugerties the subsequent 12 months. Every morning, the Band would awaken at Massive Pink and put together for rehearsals. Hudson went down early to make sure the recorder was ready for Dylan’s arrival. When the day’s classes began, Hudson sat in a nook close to his organ and hit “record.”

“The wonderful thing in working with Dylan was the imagery in his lyrics, and I was allowed to play with these words,” Hudson advised Keyboard journal in 1983. “I didn’t do it incessantly. I didn’t try to catch the clouds or the moon or whatever it might be every time. But I would try and introduce some little thing at one point a third of the way through a song, which might have something to do with the words that were going by.”

Hudson added that when he was beginning out he test-drove the extra common Hammond B-3 organ, however he was drawn to a mannequin made by a smaller firm, Lowrey. “The Lowrey had enough bite, and I could make it distort enough, to fit in with what we were doing.” The early fashions, continued Hudson, erupted with “a great distorted sound when you turned everything up.”

Hudson recorded 1968’s “Music From Big Pink” simply as he’d performed the Dylan classes. Author Marcus described the album in “Mystery Train“ with a sense of reverence: “Flowing through their music were spirits of acceptance and desire, rebellion and awe, raw excitement, good sex, open humor, a magic feel for history — a determination to find plurality and drama in an America we had met too often as a monolith.”

That album and its 1969 follow-up, “The Band,” cemented their fame among the many critics, but it surely did not register in a youth market then obsessive about LSD and psychedelic music. When the sound the Band helped forge, country-rock, grew to become a business powerhouse a number of years later, they watched as acts together with the Eagles, Lynyrd Skynyrd and countryman Neil Younger soared to the highest of the charts. The Band launched 5 studio albums between 1970 and 1976. None was a runaway business success, however the musicians remained a strong stay band. Dylan invited them to embark on a 1974 joint tour, which later that 12 months was the premise for Dylan’s first stay album, “Before the Flood.”

The Band, left, Levon Helm, Richard Manuel, Robbie Robertson, Rick Danko and Garth Hudson in London, June 1971.

(Gijsbert Hanekroot / Redferns)

Within the mid-Seventies, Hudson and most of his bandmates — drummer Helm divided his time between L.A. and Arkansas — moved to Malibu to assist create one other legendary studio, Shangri-La. With Dylan investing alongside the band, they leased a home, allegedly a former bordello, and turned it right into a state-of-the-art recording studio. Hudson purchased a close-by property he dubbed Massive Oak Basin Dude Ranch. By then, although, the Band had been collectively for practically 15 years. They broke up in 1976 amid numerous addictions and life adjustments, however not earlier than releasing “Islands,” the ultimate studio album to characteristic the unique lineup. He and his spouse, Maud Hudson, misplaced their house and belongings within the 1978 Agoura-Malibu hearth. (Shangri-La is now owned by producer Rick Rubin.)

With the Band’s demise, Hudson settled right into a constant life as a session musician, showing on data by Poco, Van Morrison, the Name, Camper Van Beethoven, Mary Gauthier and plenty of others. Minus Robertson, the Band partially reformed in 1983 to tour, and spent the subsequent three years as headliners and on payments with the Grateful Lifeless and Crosby, Stills and Nash. After Manuel’s 1986 suicide, the Band returned to the studio for 1993’s “Jericho,” however Robertson once more didn’t be a part of Hudson, Helm and Danko.

Hudson’s work on fellow Canadian Neko Case’s acclaimed ‘00s albums, “Fox Confessor Brings the Flood” and “Middle Cyclone,” reinforced the ways in which his oft-menacing organ chords and gorgeous improvised countermelodies have resonated across generations.

Garth Hudson in 2014.

(Rick Madonik / Toronto Star via Getty Images)

Approaching old age, Hudson and his wife returned to the Hudson River Valley. His life as a nonsongwriting band member meant that he didn’t personal a share of any of the Band’s songs, and subsequently didn’t obtain common publishing royalties from their work. By then, Hudson had way back offered his share of the Band to Robertson.

Maud Hudson died in late February 2022. The couple didn’t have any kids.

Alongside along with his fellow bandmates, Hudson was inducted into Canada’s Juno Corridor of Fame in 1989 and into the Rock & Roll Corridor of Fame in 1994. In 2008, he and the Band had been offered with a Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award.

Garth Hudson launched two solo albums: the cassette-only “Music for Our Lady Queen of the Angels” in 1980 and “The Sea to the North” in 2001. Mixing kinds, synthesizer and organ tones, a Vocoder voice field and a prog-rock album’s value of tempo adjustments, on each releases Hudson composes and performs as if his muse can barely include all of the concepts flowing out.